This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter.

Each year, the Department of Veterans Affairs’ internal watchdog sends a survey to all 139 of the agency’s medical centers coast to coast with a straightforward question: Which jobs have severe staffing shortages?

In fiscal year 2025, the responses raised alarm: VA health care facilities reported more than 4,400 severe staffing shortages—a 50 percent hike from the previous year.

And once again, the job that topped the list for clinical positions among VA facilities? Psychologists. It’s the same occupation that took the lead spot in 2024 and has been in the top five since 2019.

Despite suicide prevention and veterans’ mental health being one of the VA’s top priorities, there are signs that psychologists and other mental health professionals on staff are reaching a breaking point.

“I loved my veterans and had the privilege of seeing real change in their lives over time,” said Laura Grant, a psychologist who left VA in September last year after nearly a decade on the job. But “burnout increasingly felt normalized rather than addressed.”

Grant was among six psychologists who left the Department of Veterans Affairs in 2025 and told The War Horse in interviews over the past several months that mental health providers are burning out.

Last year, the number of psychologists employed by the VA dropped for the first time in more than a decade. Every fiscal year since 2016, the department has added between 55 and 350 psychologists to its rosters, according to VA workforce records obtained through a Freedom of Information Act Request. In fiscal year 2025, however, the department lost more than 200.

In the most recent VA Office of Inspector General staffing report, 57 percent of VA health care facilities reported severe staffing shortages of psychologists. Shortages are defined by the government as occupations that are hard to fill, not necessarily positions that are vacant. Psychiatrists were the second most reported clinical occupation for severe staffing shortages at 55 percent of VA facilities.

The shortages aren’t unique to VA; more than 135 million Americans live in an area with a shortage of mental health professionals. And VA says it is currently posting hundreds of job openings for psychologists.

But the psychologists who left VA in the last year told The War Horse that the agency, once renowned for top-tier training—more than half of all US psychologists get training at VA—mentorship, and work-life balance is now one plagued by metrics and pressures to discharge patients more quickly to make room for new ones.

“There was so much I loved about the VA,” said Melissa London, a psychologist who left the San Francisco VA in January 2025 after her caseload doubled over the course of two years. “The [staffing] shortage was constant, but it was never nearly as bad as it was in the past year, or two years, at least.”

A VA spokesman dismissed the criticism, called concerns from former psychologists quoted in this story “unconfirmed hearsay,” and accused The War Horse of trying to make the Trump Administration look bad at all costs, regardless of the facts.

“The number of VA psychologists fluctuates from year to year based on labor market trends and demand for their services,” said Peter Kasperowicz, VA press secretary. “Today we employ more than 7,000 psychologists, which is more than VA had at many points during the Biden Administration.”

But as the number of psychologists declines, the demand for mental health care has continued to rise. VA saw 2.2 million patients for mental health care in fiscal year 2025, according to data obtained by The War Horse. That is a 40 percent increase from a decade ago. Meanwhile, the VA has increased the number of psychologists employed at the agency by only 24 percent since 2016. Psychologists aren’t the only ones who treat veterans’ mental health; some are seen by other providers, such as psychiatrists and social workers.

Despite the staffing shortages, psychologists still have the highest retention rates for surveyed VA employees in the first two years on the job. But a recent report from Democrats on the Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs cited interviews with VA employees that indicate an ongoing “exodus” of mental health care providers at some facilities.

In a Senate committee hearing in December, Dr. Julie Kroviak, VA’s principal deputy assistant inspector general, acknowledged the trend. She said surveys found VA mental health providers “are losing clinical staff because of morale.”

Health care providers were protected from layoffs and ineligible for early retirement or deferred resignations when the VA shed more than 30,000 employees last year. VA insists it is prioritizing hiring mental health care providers, and is currently recruiting more than 400 psychologists across the country, said Kasperowicz. This week, there were 171 job postings under the code for clinical psychologist at the Veterans Health Administration in the USAJOBS portal.

However, multiple former VA psychologists told The War Horse they didn’t see evidence during their time on staff that hiring new psychologists was a priority.

A psychologist at the Bronx VA said they left their position focused on suicide prevention research and psychotherapy for veterans transitioning out of the military after their study’s federal grant funding ended. They said they weren’t able to find a new position in research or working with patients at their VA medical center, or to get the medical center director’s approval to get sponsored for a new grant. “There wasn’t any effort to provide me with bridge funding or to figure out how to keep me,” they said.

This psychologist, like some others who spoke to The War Horse, asked to remain anonymous either because they had friends or family who still worked at VA and feared backlash, or because they planned to apply for government-sponsored research grants and were worried that speaking with a journalist could lead to retaliation.

London recalled how difficult it was to hire new psychologists, including during the Biden administration. She cited hiring freezes and having to fight for new staff, even though “it was very clear to anyone in the field that additional staff was needed.”

Even before Trump returned to the White House, psychologists at VA were at a breaking point.

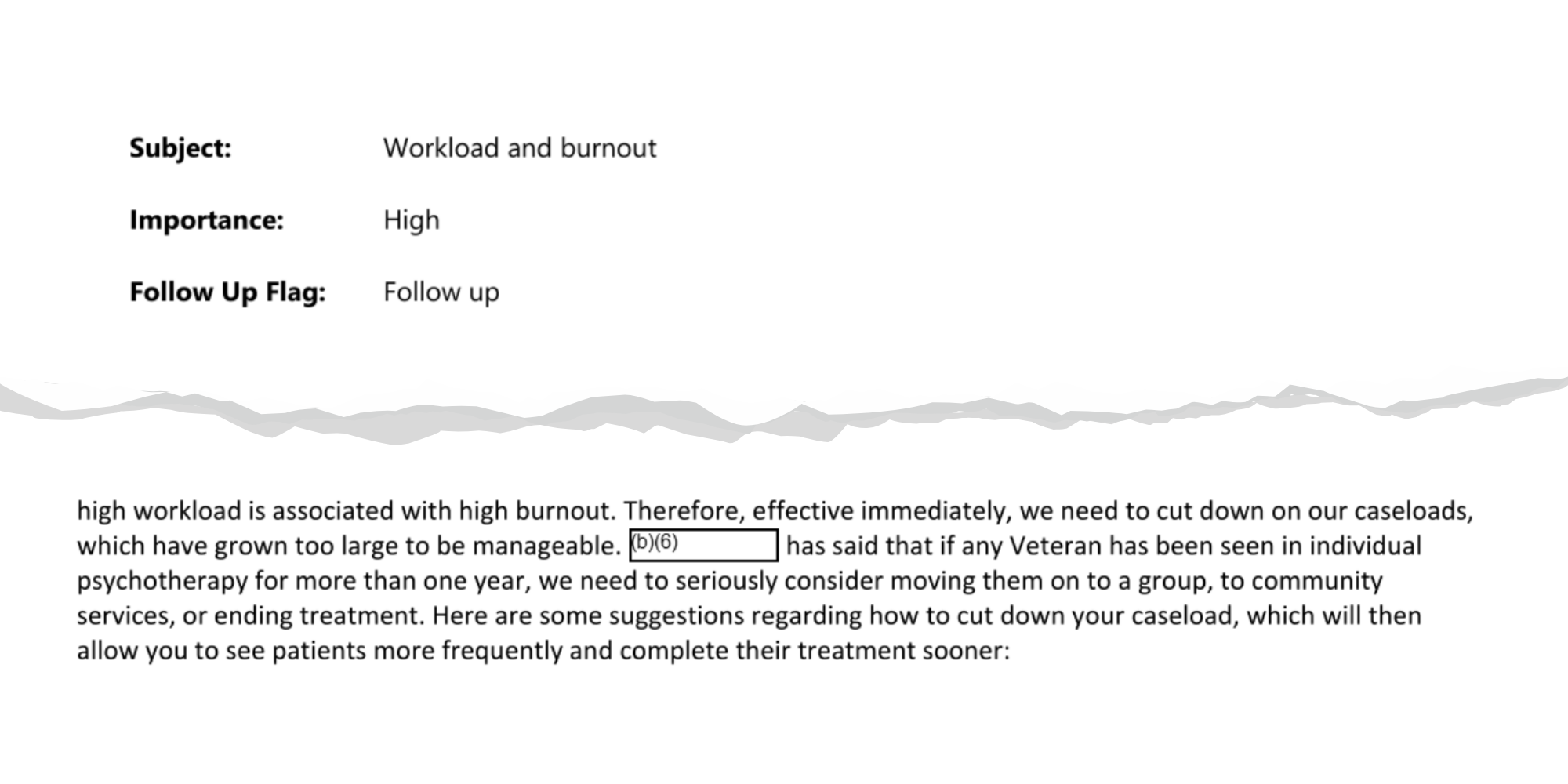

In September 2024, a psychology program manager at the Central Virginia VA Health Care System sent an email to several staff members. The subject: workload and burnout. The importance: high. In the email, the program manager stated that, since there would be virtually no new staff positions in fiscal year 2025, new strategies would be implemented to treat patients. “Effective immediately, we need to cut down on our caseloads, which have grown too large to be manageable,” they wrote.

An excerpt of an email sent by a VA psychology program manager. To read the full email, click here.

These new strategies included ending treatment with all veterans who have been in therapy longer than two to three years, pausing or ending treatment “with people who have not made progress recently and seem to have plateau’d,” telling patients they need to take a six- to 12-month break from therapy to practice skills, and starting all new patients on a short treatment model of six to 15 sessions.

“We just can’t keep seeing everyone in individual psychotherapy for long periods of time,” the program manager wrote. “It makes them dependent on psychotherapy, and it burns us out.”

A veteran, infuriated that his one-on-one therapy was cut off, later discovered the memo and tipped off The War Horse, which obtained a copy through a public records request.

The email may have been well-intentioned for both the therapists and the veterans. In 2024, a study found that when therapists are burnt out, veterans’ mental health care can suffer as well.

But one tactic to avoid burnout and care for more veterans mentioned in the email—the short treatment model of six to 15 sessions—has frustrated patients and providers, The War Horse has found.

And it isn’t unique to Central Virginia. Over the past several years, it has been rolled out at VA medical centers across the country, according to previous reporting by The War Horse.

VA has repeatedly told The War Horse that it does not have a national policy to cap mental health care.

Kasperowicz, the VA press secretary, called it “extraordinarily dishonest of you to take an email from the Biden Administration and try to misrepresent it as something that reflects the Trump Administration’s policies.”

Multiple psychologists in states across the country have told The War Horse they are still under pressure to limit one-on-one therapy.

One psychologist who left the Orlando VA Medical Center last year also said it was frustrating to frequently tell patients they couldn’t schedule future sessions for a month, or sometimes longer. “I felt like a factory worker.”

For several of the psychologists who spoke with The War Horse, the final tipping point came when Elon Musk and the Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, began rolling out initiatives in the late winter and spring of 2025—including reductions in force—that seemed designed to drive employees out. “Recognition for meaningful clinical work felt scarce, while scrutiny and suspicion became more common,” said Grant.

Grant said that one of the several reasons she quit was the agency’s dismantling of DEI initiatives, which she said “were directly tied to our ability to show up authentically, ethically, and competently for a diverse veteran population.”

Kasperowicz said VA is “proud to have abandoned the out-of-touch and divisive DEI policies of the past so we can focus solely on VA’s core mission.”

The return-to-office mandate was also difficult on psychologists, who require privacy to hold sessions with their patients. The psychologist at the Bronx VA said they didn’t have their own office and had to use the offices of absent colleagues to work. They once couldn’t find an empty office and were forced to take a telehealth appointment from their car.

“There’s no respect for what these veterans need, which is privacy…even though I love working with veterans, and I have loved being at the VA for the most part, it was just really demoralizing.”

“There’s no respect for what these veterans need, which is privacy,” they said. “I couldn’t wait to get out, even though I love working with veterans, and I have loved being at the VA for the most part, it was just really demoralizing.”

VA has been taking steps to address staff burnout, including appointing chief well-being officers whose roles are to reduce administrative burdens and improve employee wellness. This month, the American Medical Association recognized seven VA health care facilities through its Joy in Medicine program, which highlights facilities that have met specific program requirements to address physician burnout.

VA’s press secretary did not respond to The War Horse’s request to interview one of VA’s well-being officers, and few of the psychologists who spoke to The War Horse had ever heard of the officers—none had encountered them.

London said that at the San Francisco VA, there were efforts to mitigate staff burnout, like pizza parties. But many of these efforts felt surface-level. “There’s constant jokes about burnout and the memes of the pizza party,” she said, “when what we really need is a new hire.”

The majority of psychologists who spoke with The War Horse now work in private practice, where they can set their own hours and their own rates. And while some still work with veterans, none have joined the VA’s community provider network, which would allow veterans to see them through the VA’s Community Care program.

London and Grant say that issues with payments from insurance contractors and low reimbursement rates are some of the main reasons that private practice psychologists don’t want to participate in the program.

Many of the psychologists said that they would be open to returning to VA one day. One called working with young veterans “the most rewarding clinical experience of my life.” That echoes data published by the department; 69 percent of psychologists who left the agency said they would be open to returning, according to the latest workforce data available.

“I think there would have to be a little bit more respect and empathy and compassion for clinicians and some strategies about burnout,” London said. “But it’s something that I would consider if there was a clear indication that they actually cared.”

This War Horse news story was edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar.