My first visit to high altitude didn’t go well. I was at a training camp in the French Alps, and on one of our easy days my teammates and I decided to take a cable car to the summit of Aiguille du Midi, at over 12,000 feet above sea level. The ticket was enormously expensive, but I had such a splitting headache by the time we got to the top that I couldn’t even look out the window. I just huddled on a bench, head in hands, until my friends were ready to descend. It was my first and most vivid encounter with acute mountain sickness.

Since then, I’ve been curious about ways of avoiding altitude illness. As the Wilderness Medicine Society’s guidelines note, the most obvious and effective one is giving your body plenty of time to adapt—like, not ascending in a cable car, for example. The memory of that experience is one of the reasons that, when I went trekking in the Everest region of Nepal several years later, I chose to hike into the region from a town called Jiri rather than flying directly from Kathmandu. Thanks to the gradual ascent, I was able to climb above 18,000 feet with no problems.

Still, there’s always interest in quicker and more effective ways of defending yourself. For example, there’s been a lot of discussion and debate this year about the potential protective benefits of inhaling xenon gas, though most scientists say the evidence that it works is so far slim to non-existent. Another idea that has emerged with less fanfare is the potential for ketones to help ward off altitude illness, as researchers from the University of Guelph in Canada explain in a new review paper in the European Journal of Applied Physiology.

How Do Ketones Work?

Ketones are a form of fuel that your body produces when it doesn’t have carbohydrates available, either because you’re starving or on a low-carb (“ketogenic”) diet. About a decade ago, drinkable forms of ketones went on the market. There were wild rumors about their supposed endurance-enhancing effects, especially among pro cyclists. As time passed, the hype faded, but research into the properties and potential benefits of drinkable ketones has continued, for example to aid recovery or ward off overtraining.

One line of inquiry is whether they have any benefits at high altitudes. A group of researchers at KU Leuven in Belgium and the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia have run a series of studies testing the effects of ketones both in altitude chambers in the lab and in the Alps. There’s evidence that ketones can help keep levels of oxygen in the blood high, so the initial hope was that they would boost maximal exercise performance in the mountains. So far, that doesn’t seem to be the case. In fact, ketones seem to hurt maximal exercise performance. But there are reasons to think they might have more subtle benefits.

How Do You Avoid Acute Mountain Sickness?

The first-line preventive drug for acute mountain sickness, or AMS, is a drug called acetazolamide, sold under the trade name Diamox. You typically start taking it a day before you start ascending to high elevations, and take 125 mg every 12 hours. It works by making you breathe more deeply (and possibly a bit more rapidly), so that you inhale and exhale 10 to 20 percent more air per minute. That means you get more oxygen into your blood: at 11,000 feet above sea level, blood oxygen levels will be 3 to 6 percent higher if you’re on Diamox.

How Diamox works isn’t fully understood, but the main mechanism seems to be that it alters the acid-base balance in your blood. This is important because it’s the acid-base balance of your blood that cues your brain to breathe. If you hold your breath, your blood will get more acidic as carbon dioxide accumulates, which triggers an urge to breathe. Diamox does essentially the same thing. The problem is that it has side effects for some people, including numbness or tingling in the fingers and toes, nausea, headache, and fatigue. It also makes you pee a lot.

Here’s where ketones come in. As Michael Tymko and his colleagues at the University of Guelph argue in their new paper, ketones produce effects at altitude that are remarkably similar to those of Diamox. Ketones alter the acid-base balance of your blood; they increase the amount of air you inhale and exhale by about 15 percent; they boost blood oxygen levels at altitude by 2 to 4 percent. The exact details depend on how high you go, how hard you’re exercising, and other factors, but the overall patterns are very similar.

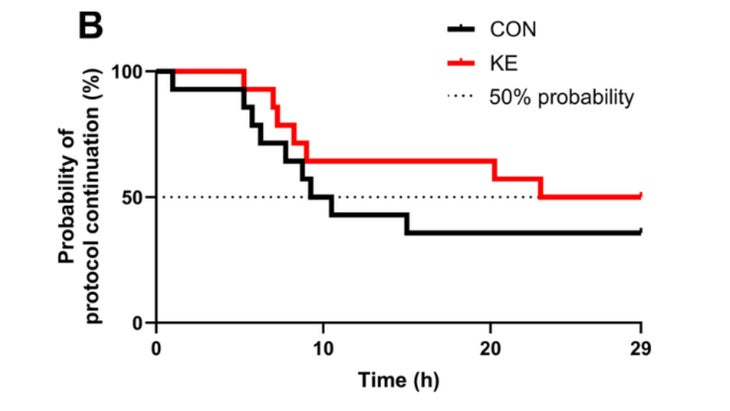

So far, there’s just one published study testing this premise. In the Journal of Applied Physiology last year, Myrthe Stalmans of KU Leuven and her colleagues put 14 volunteers through two 29-hour protocols in an altitude chamber set to greater than 13,000 feet. They completed a series of exercise bouts during the protocol to mimic the effort of climbing a mountain, and periodically consumed either a placebo or a ketone monoester drink. If a subject developed severe AMS, the protocol was terminated.

Here’s what the data looked like. The lines indicate what percentage of participants were able to continue as time passed, in either the ketone condition (red) or the placebo condition (black):

You can see that the red line stays higher than the black line throughout: taking ketones seems to help protect against severe AMS, though not perfectly. On average, subjects lasted 32 percent longer with ketones.

Tymko, too, has some data from a ketones-for-AMS field study he and his colleagues conducted last summer; the results should be published sometime in 2026, he told me in an email. As an alternative to Diamox, ketones aren’t perfect, he pointed out: they taste bad, they’re expensive, and they give some people an upset stomach. They also have a relatively short half-life of a few hours in the body, so you have to keep taking them throughout the day, though the optimal dosing protocol hasn’t yet been determined. But for people who get side effects from Diamox, they might turn out to be a useful option.

For more Sweat Science, sign up for the email newsletter and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.

The post Why Ketones Might Ward Off Altitude Illness appeared first on Outside Online.