On a cloudy morning in late January, I heat up in the floating sauna until sweat beads down my face. I then step out into the biting air and take in Oslo’s half-frozen harbor, where its white angular Opera House rests like an iceberg. As I nervously look down to a ladder leading to the ice-speckled fjord below, I let out a slow shhhhh, inching my way down in the water as it sends pounding jolts to my bare skin. Less than a minute later, I climb out and dash into another wooden sauna on the same floating dock, before I do it all over again.

My love for this hot-cold Nordic ritual began in 2018 on my first trip to Finland, the birthplace of sauna, but it’s here on my first trip to Norway, seven years later, that my obsession gets more focused: floating saunas. They have all the things I love in one: steamy warmth, being afloat on the water, and invigorating cold plunges.

The beauty of these saunas that bob in Oslofjord is that they’re affordable—unlike the saunas back home in Brooklyn, New York. On a mission to “bring sauna to the people,” Oslo Badstuforening (Oslo Sauna Association) is inspiring a worldwide movement to make the Nordic bathing tradition accessible for everyone. One of their 19 public floating saunas in Oslo is the world’s first wheelchair-adapted universal sauna that’s made out of recycled sustainable materials.

Fortunately, I no longer have to leave the country to enjoy my love of Nordic sauna culture. The sauna and bathhouse movement is expanding rapidly in the United States, with the market projected to grow $150 million over the next four years; every month, it seems, a new sauna opens stateside.

Unlike artificially lit and windowless spas, floating saunas have the extra appeal of being immersed in nature—something urban Finns and Norwegians have access to more readily than many city-dwellers in the U.S. New York state’s first floating sauna, Kos, opened this fall in Saratoga Springs, a historic town upstate known for its healing mineral waters. Its American founder, Kate Butchart, was inspired by the floating saunas in Oslo she frequented while living there for seven years. Butchart dreamed of bringing her daily practice—especially helpful for surviving harsh winters—home with her.

Kos is designed by Norwegian architect Bjørnar Skaar Haveland, who operates a similar community-driven floating sauna in his hometown of Bergen, Norway.

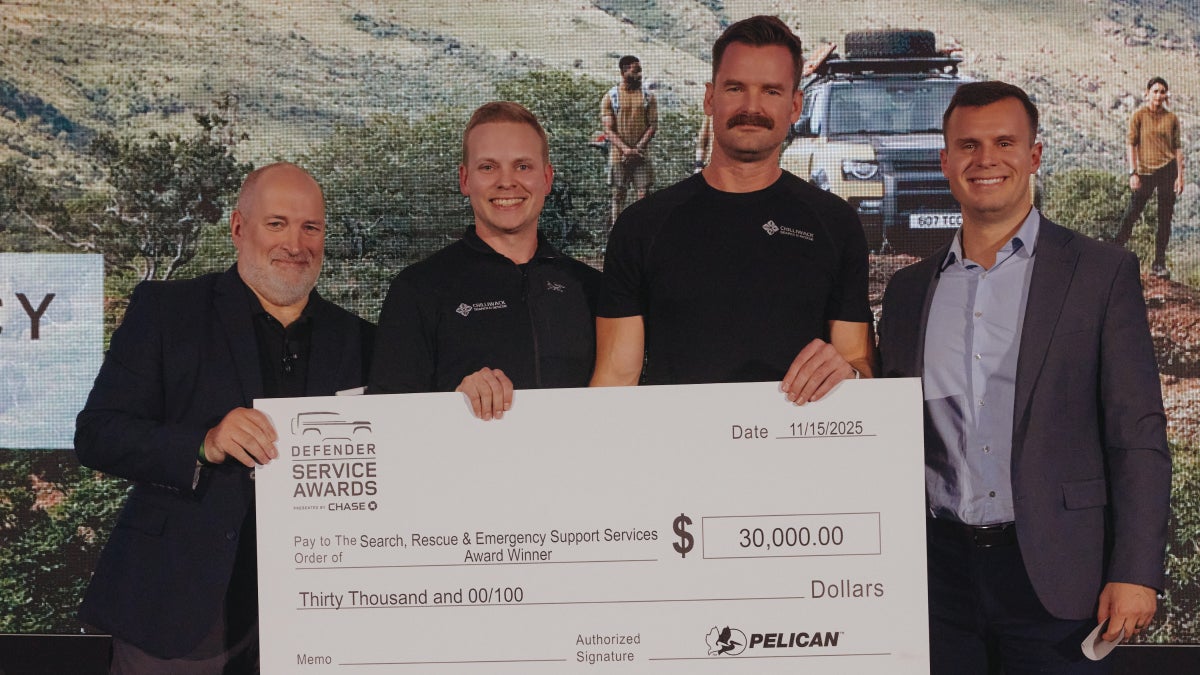

One of the first public floating saunas in the U.S., Cedar and Stone in Duluth, Minnesota, was similarly inspired by its founder’s time in the Nordics. Justin Juntunen visited a floating sauna in Turku, Finland, on a heritage trip in 2011 tracing his ancestry. He decided then and there that he wanted to open a floating sauna in his hometown of Duluth, which at one point had so many Finnish immigrants (it has one of the highest concentrations in the U.S.) it was called “Little Helsinki,” and the neighborhood around its Canal Park was dubbed “Finn Town.”

A month before the pandemic started, Cedar and Stone opened their first public sauna on Lake Superior, and in 2023, their flagship floating sauna opened on a renovated barge. Later that year, their rooftop sauna debuted at the Four Seasons Hotel in Minneapolis. The company also designed and built Othership’s new 100-person sauna, which opened in Brooklyn in September. Cedar and Stone also offers an accelerator sauna business course for a growing community of “saunapreneurs.”

Why is there such a growing demand for a place to sweat it out with strangers? For one, saunas are seemingly the last social space where you can’t be on your phone. This inherently leads to a pause in your day and, even if you sit in silence, a way to connect with others.

The loneliness epidemic is a global public health concern, and saunas are creating new democratic social spaces to help cure it. During the pandemic, we realized how desperate we were for daily escapes in nature and moments away from our screens.

“Traditional sauna is timber from the land, rocks from the soil, and fresh water from nearby,” says Juntunen. “You put those together with heat, and you have some of the best ingredients for great sauna. This place-based experience gets people into nature and into their bodies, and floating sauna as a concept, gets people also into the water.”

Cedar and Stone (Duluth, Minnesota): Resting on Lake Superior, the world’s largest freshwater lake by surface area, Cedar and Stone is built on a 40,000-pound barge, making it an epic spot for some serious contrast therapy. This pioneering floating public sauna is inspired by the city’s—and the founder’s—Finnish heritage. (Photo: Courtesy Cedar & Stone)

Cedar and Stone (Duluth, Minnesota): Resting on Lake Superior, the world’s largest freshwater lake by surface area, Cedar and Stone is built on a 40,000-pound barge, making it an epic spot for some serious contrast therapy. This pioneering floating public sauna is inspired by the city’s—and the founder’s—Finnish heritage. (Photo: Courtesy Cedar & Stone)Beyond being a place to connect in a healthy social space—and disconnect from the stresses of daily life—floating saunas have another added societal benefit. They remind us of our need for clean water. That cold post-sauna dip wakes us up to how important pollution-free places to swim are to our well-being and our communities.

“We’ve lost our ability to bathe and swim,” Juntunen says. A hundred years ago in the U.S., we had public bathing facilities and bath houses on the Mississippi River, in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and among many other places, he adds. With the revival of swimmable cities such as Paris and Chicago, Juntunen tells me I shouldn’t be surprised if New York City opens a floating sauna on its rivers in the near future.

“To get people to care about water, you have to get them in and around it,” the saunapreneur says. “[As you] cold plunge into Lake Superior—you care about it when you’re in it, because you feel it. And there’s beauty in that. We’re teaching people how to conquer winter. They jump in the cold water in their bathing suit. They get out, and it’s ten degrees, or negative ten degrees outside, and they feel like they ran a marathon.”

The feel-good effects of a physical challenge in nature with a community to cheer us on? Bring it on.

The post Sweat. Plunge. Repeat. Floating Saunas Are on the Rise Across the Country. appeared first on Outside Online.