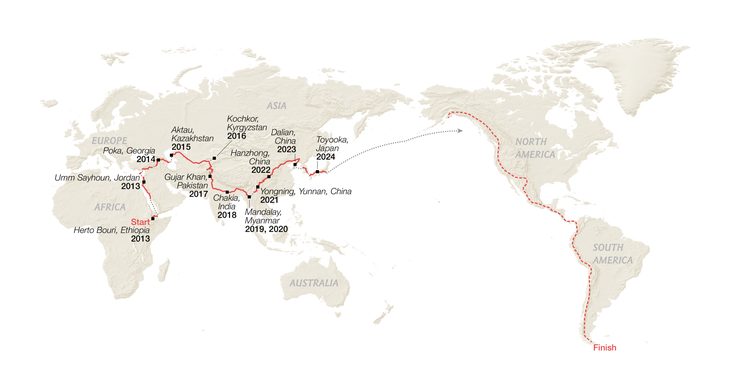

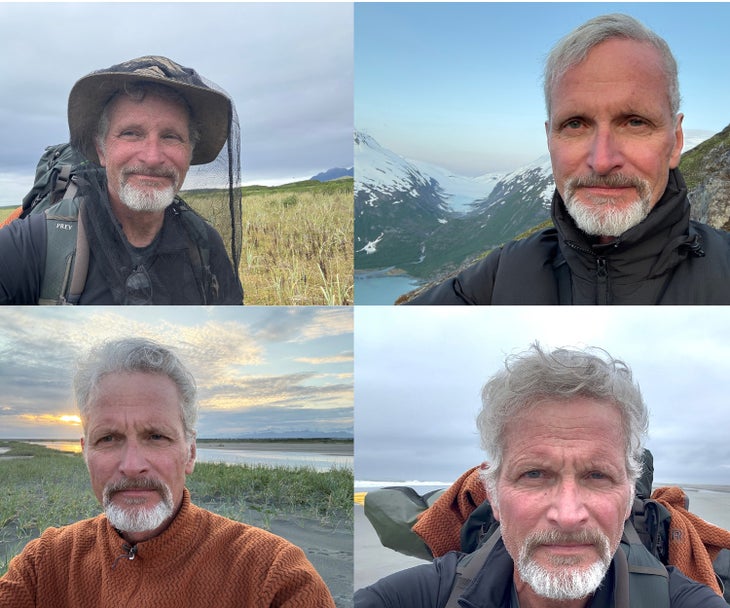

In 2013, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Paul Salopek walked out of Ethiopia’s Rift Valley, the beginning of a seven-year journey on foot to follow the trails of the first Homo Sapiens. Two continents and 13 years later, Salopek has returned to North America for the first time in over a decade to continue his worldwide trek. This spring, he will begin the final phase of his 24,000-mile odyssey—walking to the southern tip of South America. Outside caught up with Salopek during a layover in Gustavus, Alaska.

I was born in Barstow, California. At five and a half years old, I moved to the central Mexican plateau with my parents. When you take any kid into new environments outside of their social frontier and expose them to a new language, culture, and a new human landscape, it leaves a big impression. That probably led to subconscious decisions, which led me to be a foreign correspondent and an international journalist.

I’ve walked in the ballpark of 18,000 miles. So far, so good. It’s just the luck of the draw of genes. I’m skinny by predisposition and walking is pretty low impact, so no complaints. I don’t even get blisters. Go figure.

I’m not on Strava. That’s not the kind of project this is.

I carry a canvas bag with arm straps. That’s intentional. It’s not a statement of Thoreauvian simplicity. It’s fewer things to break. I try to keep the weight under 26 pounds if possible. This is maybe one of the secrets of having a fair amount of knee cartilage left.

The whole seven-year thing was a calculation on a napkin, basically, where I just said, “how far can a person in reasonable health walk in a day?” and I said, “OK, it’s x miles a day.” Then I cut it in half because I’m a reporter. Divide that into how many miles it is to walk from the horn of Africa to South America, and that adds up to seven years. The ridiculousness of that was apparent to me even back then. It’s a number grasped out of thin air because life happens. You run into things like borders. You can’t walk through Iran. Iran won’t give you a visa. It’s a bloody big place; you have to walk around it.

The way I try to think about “slow journalism” is that it’s not just about slowing down. It’s much more profound than that. It’s the whole way of looking at how current events shape the lives of each one of us. Slow journalism implies having a hunter-gatherer mindset where you don’t know what the story is. You go out open-minded into the world to find the stories or have them find you.

The way I think of this walk is that there are corridors, the way ancient people probably moved. They didn’t have destinations because destinations hadn’t been invented. They didn’t know where they were going. That’s why I don’t often use the word migration because that implies knowing where you are going. They went not only forward, but often sideways and sometimes went backwards. I’m kind of in the same boat.

It took more than four years of effort to get a China visa. Originally, I was going to walk from Central Asia through western China, and they did not want me in western China. I ended up walking south through the Pamirs and the western Himalayas into Afghanistan and then into Pakistan and then into northern India. I’m very philosophical about this. One, the ancient peoples I’m following did the same thing. Also, wonderful things happen on detours.

I was really looking forward to Siberia; amazing literature comes out of Siberia. I was in Manchuria, close to the Russian border and the invasion of Ukraine started to make that option untenable. Finally, a few hundred kilometers from the Russian border I had to make a conflicted and painful decision to turn around and say, ‘I’m not going to risk walking through Russia at this time.’ So, I turned around and walked a long way back to a port—435 miles. I took a ferry boat from a port in China to South Korea and walked across South Korea. I had never been there. It was incredible.

At the beginning I walked with pastoralists, camel and goat herders. In Saudi Arabia it was a Saudi journalist and a retired Saudi special forces officer who was a desert survival expert. In Jordan it was a guy who volunteers on archeological sites. In China I walked with a conceptual artist who walked through parts of Vietnam and huge chunks of western China sometimes backwards. One of the great gifts of the walk is who you walk with. There’s something about walking that unlocks friendship very quickly.

This project is driven by hope. I’m taking this literally one step at a time. But hopefully, if I do reach the tip of South America, it will be kind of a cool thing to have this record of a journey that is so inclusive. The people that I meet, these encounters with strangers who then become friends and, in some cases, save your life, is a powerful affirmation for me, about through all the crud and all the darkness that we have to wade through, there’s still a kernel of light. You’ll find it. It gets proven out in one form or another almost every day that I hit the trail.

I don’t have high points or low points. It’s like walking across landscape, the topography. There are highs and lows that are then followed by other highs and lows. There are painful parts of the journey, walking among the refugee communities, the millions of people who fled Syria and seeing people living on nothing but tomatoes, including infants. But there are many, many, many more highs. The high points for me are the people that I’ve met, the people who have taught me and succored and tested me along the way.

Walking is like a meditation—it unleashes this kind of movie in your head about your life that you play over and over again. It’s this internal reexamination and kind of a reverie that happens simultaneously when your neurons are firing because they are being exposed to the outer world. You’re feeling the sun on your skin, you’re hot and sweaty, your big toe hurts or you’re thirsty or you hear beautiful birdsong. There’s something about walking, this inward outwardness happening simultaneously that I think cannot help, if not make you a better person, at least a more empathetic one, including to yourself.

I was in Alaska years ago. I was in college in the summers coming up to work on a slime line in a salmon processing plant. This gigantic state is fairly new to me. I happened to bump into a friend of a friend of a friend who knew this coastline in southeast Alaska. The way I compare it is like walking from Los Angeles to San Francisco with one village in between. A lot of bears. I was thinking I’d walk in through the Alcan. No, I cut a corner, I took a raft down the Copper River and walked down the mouth of the Copper south toward Gustavus. It was such a great opportunity. I got to see the wildest, longest coastline that very few people see. Sometimes wonderful things happen when you’re knocked off course.

I won’t be walking along the U.S. coastline. I think I may be walking along the Continental Divide. Small farm roads, ranch roads, communities, big cities, but also small communities. Kind of get a yin-yang of the American West.

Come walk along if you need a break.

As told to Stephanie Pearson.

The post What It’s Like to Walk 18,000 Miles Across the World appeared first on Outside Online.