Every outdoor adventurer knows the nervy feeling of a close brush with danger, but few know it quite so well as Simon Winchester. Ever since he started working as a travel journalist in the sixties, Winchester has made a career of writing about thrilling and treacherous journeys, from sledding through Greenland’s ice caps to summiting an active volcano. At 81 years old, the author’s days of courting danger are behind him, but he still has ample advice for budding adventurers, from what to pack to how to revive a frozen colleague.

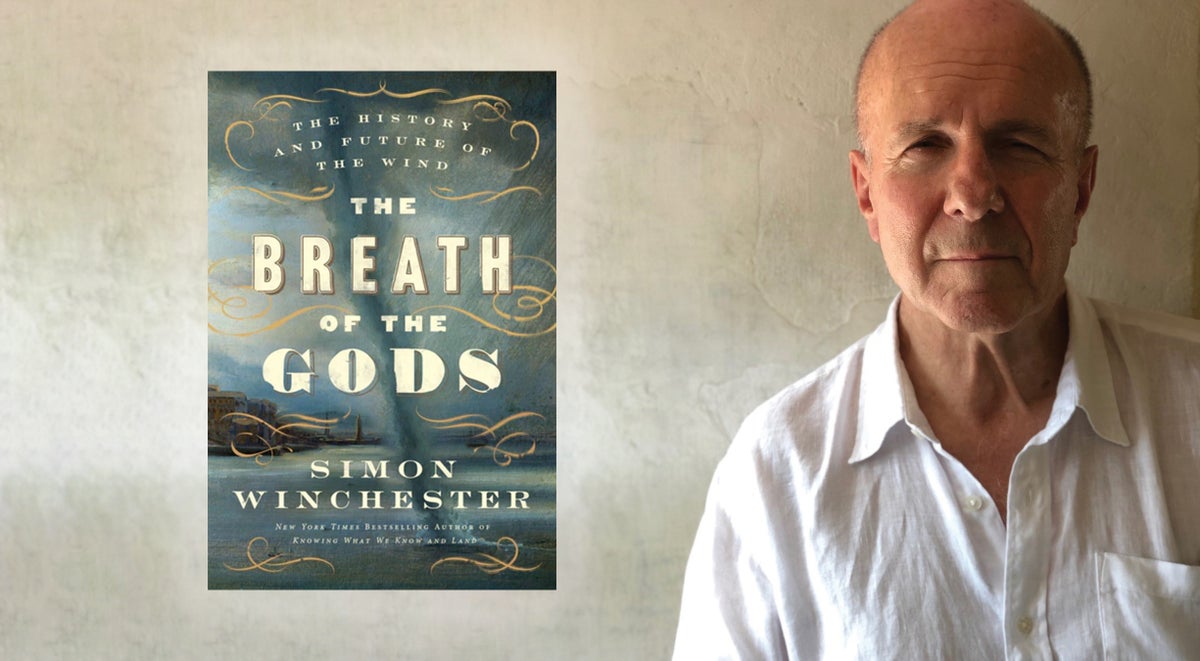

Winchester is the bestselling author of 30 books. His latest, The Breath of the Gods: The History and Future of the Wind, combines geology, meteorology, and history in a survey of how the wind has shaped human lives, from ancient sailing ships to disastrous tornados. The book also assesses the future of the wind, exploring the promises of wind power and the gusty dangers of climate change. The Breath of the Gods hit shelves on November 18.

We caught up with Winchester to talk about his most harrowing outdoor adventures, what geology has taught him about reading landscapes, and why he always travels with a squash ball.

Outside: What’s one of your earliest memories of getting outdoors and enjoying nature?

Simon Winchester: When I was at Oxford studying geology, we went on field trips to amazingly fascinating corners of the world. Once, we went to the Isle of Arran, where there’s a mountain called Goatfell. Waking up on Goatfell was a revelation to me, because it was the first mountain I’d ever been on. I grew up in North London, so there wasn’t much delight in terms of the outdoors, but Scotland, and particularly the extraordinary geology of Western Scotland, kindled a lifelong love in me. People always ask me, “You’ve traveled all over the world—where’s the place you like most of all?” Without a shadow of doubt, it’s the Western Isles of Scotland.

How does your background in geology influence the way you experience the world?

I lived in India for many years, and often I would go up into the foothills of the Himalayas, which are only a few hundred miles north of Delhi. Once you leave the city, everything’s flat, until a moment about two and a half hours outside of Delhi, when suddenly you feel your back pressed into the seat of the car, and you realize that you’re climbing. As a geologist, I would know instantly that this was the beginning of a subduction zone that created the Himalayan mountain range. I knew it was going to get cooler, greener, and more beautiful, and soon, I’d see snow. That sensitivity to subtle changes in the landscape is born of a geological understanding.

What’s the most dangerous situation you’ve ever experienced in nature?

A long time ago, I was traveling with a photographer for Conde Nast Traveler, and we were climbing Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines. It had blown its top off and left behind a typical crater lake. There happened to be a plastic kayak, and I decided I’d like to row out to the middle of the lake, where the water was still bubbling with sulfurous gases. So I paddled out, and what I stupidly didn’t realize is that once you’re over the bubbles, two things will happen. The water is going to get extremely hot, because it’s nearly boiling. And because it’s full of bubbles, it ceases to be buoyant. So two things happened: my canoe started to melt, and it started to sink, too. The photographer was really worried that I was not merely going to drown, but be boiled alive. Luckily, I got out just in time.

Was there ever a time where you weren’t sure if you’d survive?

Greenland comes to mind. I went there in 1965 to collect rock samples as part of a six-member expedition. We each had a 60-pound box of rocks, which we took down the glacier. When we arrived at the sea, the plan was that a little Eskimo boat would meet us and take us to the north side of the field, where there would be an icebreaker on a regularly scheduled trip from Copenhagen. We would get on it, and it would take us back to Europe. However, when we saw the sea, it was completely covered with pack ice. I radioed the boat, and the captain said, “I can get to you, but only if you walk out over the ice floes.” With 60-pound boxes of rocks on our backs, it was very, very risky, but we roped ourselves together and started to walk, jumping from floe to floe. After about 24 hours, we came upon a small boat. It was only able to approach about eight feet away from us, so we had to jump. Everyone made it except our leader, John Rutledge, who went straight through the ice. We belayed him, and when he came up, his beard instantly froze. In that situation, you don’t feed someone brandy—you just hug them and use your body heat to revive them.

When we got to the north side of the field where the icebreaker should have been, it had already left. Someone said the only way to get out was to call a pilot over in Iceland who specialized in rescuing people. So I radioed him, and he agreed to come. He said he wouldn’t take any money from us, but he asked that we build him a runway. So we cleared the land of any big rocks, and we lit oil cans with kerosene rags—that was our rudimentary runway. He came in a little Cessna 172, which could only take three of us at a time, as well as our precious rocks. We drew lots to determine who went first, and I was in the second group. So he landed and took three of us to Reykjavik. Then it started to get dark, and it started to snow—it was a nightmarish, hellish scene. But he came back, and before too long, we were in the comfort of a hotel near Reykjavik Airport drinking beer and thinking, what was all that fuss about? The next day, once we were back in London, we learned that the pilot had been killed in an accident that morning, and we were the last people he ever rescued. The whole narrative arc of that trip, I’ll never forget it.

How do you deal with fear in these situations?

Honestly, I’m not at all courageous. I can hardly swim. I’m a very bad bicycle rider. I deal with these little things very badly. But somehow, when major systemic failures take place, something

in me rises to the occasion. I once spent three months in prison in southern Argentina for allegedly being a spy. People asked me, “How did you deal with being in prison in Tierra del Fuego?” I said, “I went to an English boarding school, so it was very easy for me.”

What do you always pack for these adventuresome trips?

I always pack a squash ball. Invariably, if you come to some low-budget hotel, there won’t be a plug in the sink. But a squash ball can always be plugged into that hole, allowing you to fill the sink with water.

How has your relationship to the outdoors changed as you’ve gotten older?

Now I’m much more cautious. I’m always holding onto the banisters when I go downstairs, particularly in icy conditions. I drive much more cautiously. There’s a famous book about a chap who parachuted inadvertently into the Brazilian rainforest; he called it The Jungle Is My Friend. He argued that we need to learn to live with nature, and to recognize that it can be a benign force. That’s true if you’re a 25-year-old parachutist. But as you get older, you begin to be less aware of the friendliness of nature. I love the outdoors, but now, it’s a more anxiety-filled environment.

What’s your favorite way to get outside nowadays?

Anything to do with the sea. When I was 17, my ambition was to join the Royal Navy, but I’m colorblind and couldn’t do that, which is why I became a geologist. So if I can get on a ship of any size, I’m happy. Even riding the little ferry to Governor’s Island in New York brings joy to my heart.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

The post Legendary Adventurer Simon Winchester on Wind and Surviving Boiling Lakes appeared first on Outside Online.