A few months ago, I wrote an article about running and colon cancer. While researching it, I came across a new study showing that exercise extends life for people diagnosed with that condition. I didn’t pay much attention to it, because its results seemed obvious. After all, exercise does everything. You’ve got colon cancer? Of course exercise will help.

But I now realize that I missed the study’s true significance. It wasn’t just another study. It was the first time a randomized trial—the gold standard in medical evidence—had shown that exercise extends life in cancer patients. Lots of studies show that exercise improves quality of life or reduces esoteric markers of inflammation or increases some obscure cellular function, but extending life is a big deal. In fact, this may well be the first time a randomized trial has shown that exercise extends life in any context. It’s a significant milestone, and there are a few important takeaways to consider.

Some Evidence Is Better than Others

A frequent lament in exercise science is that the studies are either small or poorly designed. If you have eight subjects in your study, how do we know the results weren’t a fluke? If it’s not a randomized trial, how do we know there aren’t confounding factors skewing the findings? That was the worry with all the previous observational data suggesting that exercise might help colon cancer patients. Maybe those who exercised the most happened to be those with the least severe disease or the least aggressive form of cancer, which is why they seemed to live the longest.

In the new study, which was led by Kerry Courneya of the University of Alberta and Chris Booth of Queen’s University and published in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers recruited 889 patients from 55 different health centers in six countries. All had undergone surgery and chemotherapy between 2009 and 2024; half were randomized into a three-year partly supervised exercise program. Those who got the exercise program were 37 percent less likely to die during the study’s follow-up period and 28 percent less likely to have a recurrence of colon or other cancer.

What’s buried in those numbers is how gargantuan a task this was. I recently had a chance to chat with Booth, a former university middle-distance runner who I occasionally locked horns with back in the 1990s, and he put it in context for me. He came up with this idea during a research fellowship more than 17 years ago, and wrote the first draft of the study protocol as a class project for a course on clinical trial design. His daughter hadn’t been born when the trial began; she graduated from high school a few weeks after the results were presented. We wish all studies were this rigorous, but there’s a reason most aren’t.

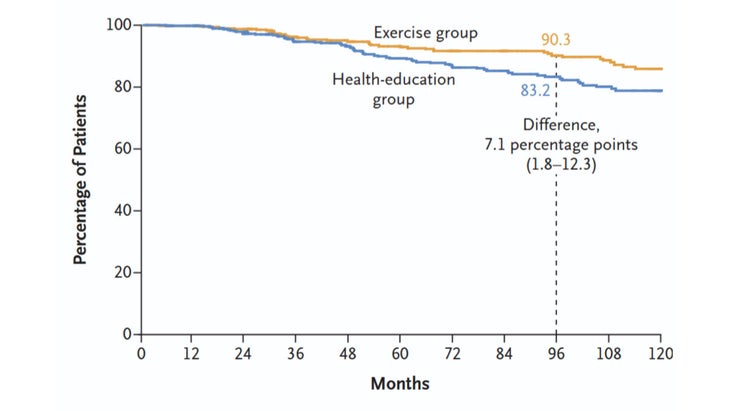

The payoff, to me, is the graph below. It shows the percentage of patients who were alive a given number of months after they enrolled in the trial.

There were 445 patients in the exercise group, 444 in the control group. After eight years, 41 of the exercisers had died compared to 66 of the control group. If I get colon cancer, I know which group I want to be in. (There’s also good reason to think the same logic applies to other cancers, since the mechanism may be related to systemic effects such as reduced inflammation or improved blood sugar control. In support of that view, the exercise group was also significantly less likely to develop new cancers in other parts of their body.)

Telling People to Exercise Is Not Enough

It’s important to note that the control group wasn’t just set adrift. They were given health-education materials telling them about the importance of exercise. This is akin to the general public health advice we’re all bombarded with: exercise is good for us, and we all know it, but that doesn’t necessarily get us out the door.

Courneya is an expert in behavior change, and he designed this aspect of the study. For the first year, the patients had supervised exercise and “behavioral support” sessions with their exercise coaches every two weeks. For the second and third years, it was once a month. They were free to choose any form of aerobic exercise they wanted, with the goal of increasing their weekly activity by about 10 MET-hours per week, which corresponds to about 2.5 hours of brisk walking. Most of the participants ended up choosing walking as their activity of choice.

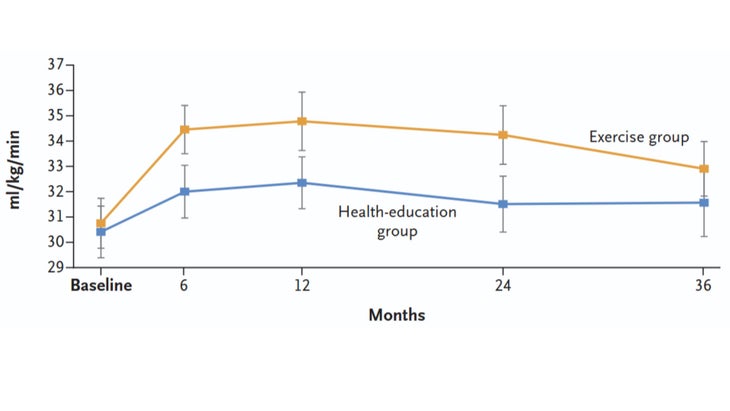

That support and accountability were crucial. It doesn’t mean the patients showed up for every session. By the third year, attendance at the mandatory behavioral support sessions averaged under 60 percent. But it was enough to keep them on track and produce measurable increases in both physical activity and in objective measures of fitness like VO2 max. Here’s estimated VO2 max (on the vertical axis) in the two groups based on a walking test, over the three years of the exercise program:

To their credit, the control group managed to boost their VO2 max to some degree too, perhaps because the health education spurred them to exercise. But the coached group outstripped them by a wide margin.

Coaching Is Not a Frill

All of this makes a convincing case that exercise should be an important treatment option available to cancer patients. As Booth and his colleagues point out, the magnitude of the benefit seen here is comparable to what you get from new cancer drugs that cost $100,000 to $200,000 per year. The exercise program provided in the study, in contrast, typically costs around $3,000 for the entire three-year period. Unlike drugs, however, this type of cost generally isn’t covered by health insurance.

Booth and his colleagues are currently running the numbers on a more rigorous cost-benefit analysis for the program, but it seems clear that any investment in supervised exercise will more than pay for itself in the long run. Still, it’s hard to get past the feeling that being told how and when to exercise is somehow less tangible—and less worthy of paying for—than a drug or a medical procedure.

That’s a feeling I had to grapple with several years ago when my wife and I were encouraging my parents to work with a personal trainer. In hindsight, that arm-twisting is one of the best things I ever did for them. And ultimately, that’s why the new colon cancer study is so important. You may say—as I initially did—that the results were obvious and entirely predictable. But if we really want to change how people approach their health, we need more medical-grade evidence like this.

For more Sweat Science, sign up for the email newsletter and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.

The post If Exercise Is Better Than a Drug, We Should Test It Like One appeared first on Outside Online.