I was in second grade when I learned that outdoor spaces were not meant for me. It was also when I realized that I was Black. Honestly, “realized” isn’t the correct word—more like declared. It was recess. The air was a little chilly, and the sky was gray. My classmates and I were pretending to be Star Wars characters. Another girl, who was white, and I both wanted to play Padmé Amidala. We bickered back and forth until a second white girl looked at me and spat out: “You can’t play her, because you’re Black and you look like poop.” The other kids, mostly White and one Latino kid, laughed. I laughed, too. Not because I thought it was funny, but because I laugh when I’m uncomfortable or angry. I immediately felt out of place. I didn’t want to play anymore. I walked away, found a spot to sit along the wire fence enclosing the playground, and stayed there for the rest of recess.

This is a memory I’ve frequently cycled between replaying and burying in my mind throughout my 31 years of living. But, most recently, it was Netflix’s newest true crime documentary told through hours of bodycam footage, The Perfect Neighbor, that hauled this memory—one that impacted my identity and self-worth for years—from the depths of my brain to the forefront.

The Perfect Neighbor opens with an aerial view of a complex located in Ocala, Florida. Large green lawns are dotted with ivory homes, and a wide paved road cuts through the complex, marking the battleground of a two-year-long dispute between Susan Lorincz, a white woman, and 35-year-old Ajike, “A.J.,” Owens’ four children—all of whom are Black. Lorincz, who referred to herself as “the perfect neighbor,” was known around town as anything but. She frequently took issue with Owens’ young children and other neighborhood kids playing outside. Her disdain for their typical adolescent activities–football, cartwheels, hide-and-seek—manifested in several episodes of verbal harassment, racial slurs, and dials to 911. She, allegedly, even waved guns at them. Tension brewed and came to a devastating head on June 2, 2023, following an argument between Lorincz and Owens that ended in the latter’s tragic death. Lorincz was convicted of manslaughter with a firearm in November 2024 and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

It would be an understatement to say that this story rocked me to my core. Watching Lorincz target those kids just for having fun outside transported me back to that time on the playground during recess, where my Blackness—not my emphatic and slightly obnoxious “I-am-Padmé” declarations that matched the tone and volume of those spouted from the girl I argued with—sucked the joy out of playtime. I was left to reckon with, yet again, that damn Star Wars game.

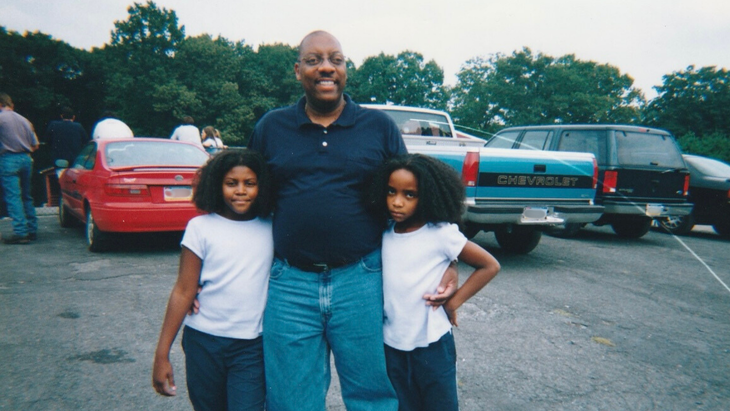

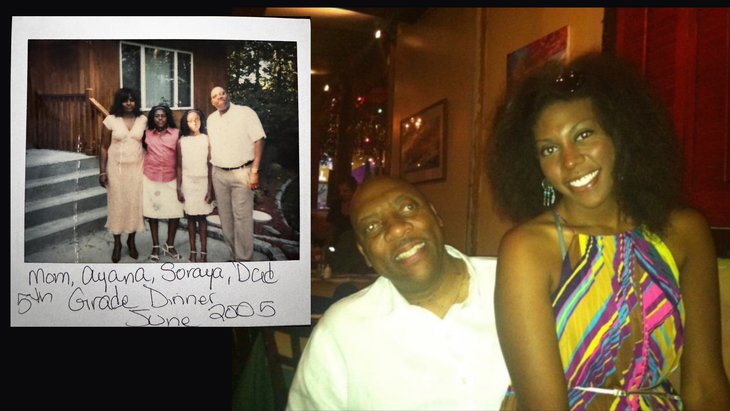

I’ve always loved being active and getting outside. My dad owns a printing company, so he sets his own hours. This meant he was home with my twin sister and me a lot as kids. We went bike riding, flew kites, climbed trees, and went paddleboating. Every Tuesday night, while I was still in grade school, the three of us met up with my uncle at the YMCA to swim. Sometimes, we’d go to an open field, lie in the grass, and watch the Blimpie blimp fly overhead. My dad, mom, and uncle were always around. It was almost suffocating at times. It wasn’t until I became an adult that I understood where their fierce protectiveness came from.

For me, the outdoors is a place where I find peace, an escape from my laptop or my apartment. But it’s also where my hypervigilance peaks.

I can’t remember exactly how old I was when my dad first gave me and my sister “The Talk,” not the sex talk. The Talk that most Black kids are familiar with: about how to be Black in America. While my dad’s tone was gentle, there was a sense of urgency and warning underneath it. Even when I was young, I got the feeling he was telling me this because he’d lived it himself. I was instructed to never be too loud, never leave my sister’s side, and never answer the door.

I recall a moment where I was in the middle of the road in my uncle’s neighborhood, kicking around a water bottle left lying on the ground. Me, my sister, and my dad had just left the community playground and were on our way back to my uncle’s house. His neighbor, an older white lady, admonished me for punting the bottle around, to which my dad said, “She’s just having fun.” The woman then proceeded to badger my dad with questions about where we were from and if we all lived together. “We live together,” he replied. She pressed him further. “But where do they—referring to my sister and me— live?” My dad firmly told her that my mom, sister, and he all live together under one household as a family. I didn’t fully understand what had just happened. He later told me that “a lot of white people can’t understand that a Black father would live under the same roof as his children.”

The Talk evolved as I got older. In high school, he told me I had to be twice as good as my white peers to get half of what they had. When my dad taught me how to drive, I learned that I should never have my music too loud and that if the cops ever pull me over, I should keep both hands on the wheel. Now, I love to go for long runs in the park or rent a bike when I don’t feel like running. I remember my dad telling me to always pay attention to my surroundings and not have the music in my headphones so loud that I can’t hear if someone “runs up on me from behind.”

For me, the outdoors is a place where I find peace, an escape from my laptop or my apartment. But it’s also where my hypervigilance peaks. Instead of only having to worry about encountering a rabid raccoon on the trail, falling, or getting lightheaded if I neglect to fuel properly, I’m also worried about which white person is staring at me like I don’t belong. I worry if I look intimidating or angry—or like I’m going to attack someone. I fear that if I cover my hair with my sweatshirt’s hood, even to just protect my ears from biting winds, someone will think I’m a criminal. So, I just let my ears get cold.

The outdoors is supposed to be for everyone. But who is everyone? If Owens’ four Black children, Israel, Isaac, Afrika, and Titus, can’t play outside without being verbally attacked, then who can? I don’t know the answer to that. But I think not having that answer is one of the reasons why I took this job as an editor at Outside. I ache to see that day when people who look like me can enjoy the outdoors without fear of being deemed a nuisance, a threat, a stain. I’m still going to go for a run tomorrow, not just for the second-grade version of myself who never got to be Padmé, but for Owens and for her four Black children—who dared to play outside.

The post Netflix’s New Documentary ‘The Perfect Neighbor’ Forced Me to Reckon with What It Means to Be Black Outdoors appeared first on Outside Online.