When I located Carl Cocchiarella on a hillside at 10,500 feet, after hiking for hours toward a blue dot on my phone, he was eating lunch in the shade of a large spruce, blended with the terrain like the savvy hunter he is. His $2,000 compound bow rested in the dirt. He chomped into a flour tortilla slathered in peanut butter while reclined next to his hunting partner, Teig Olson.

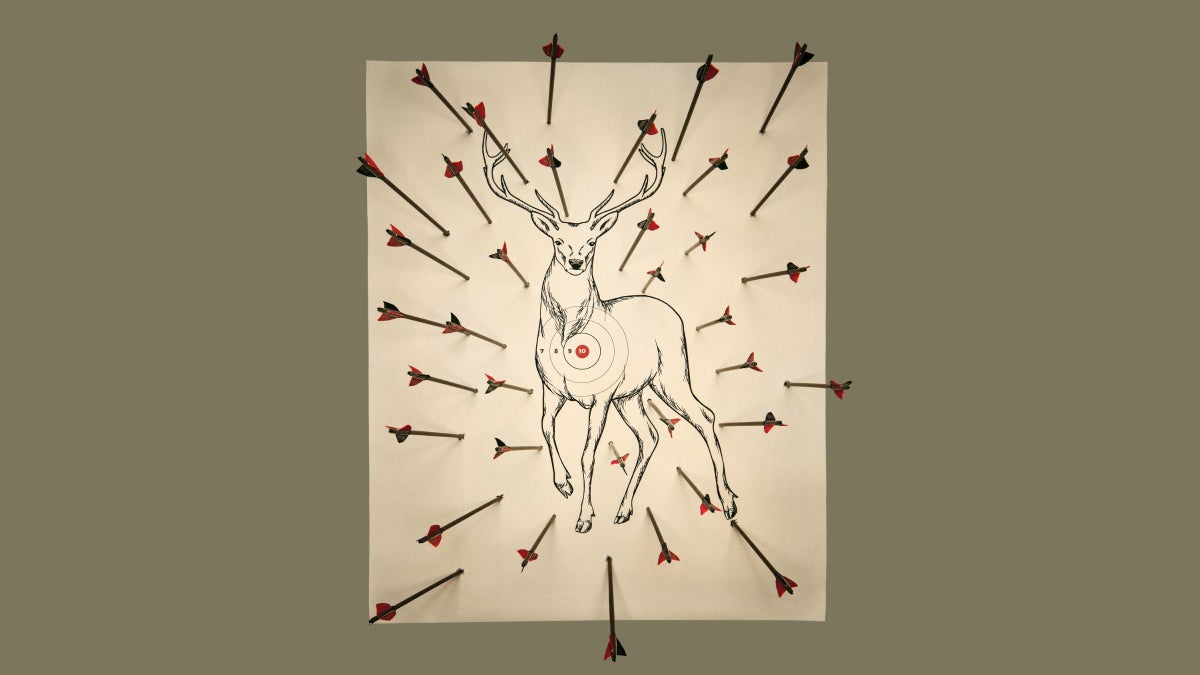

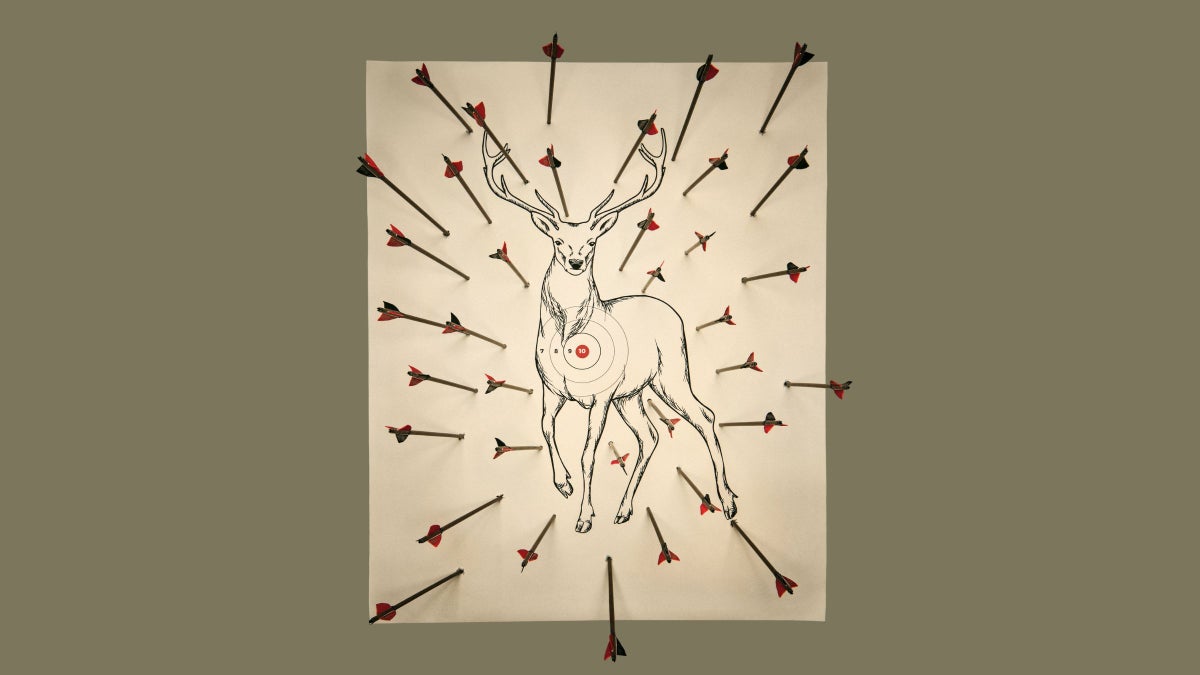

I would give you a rough idea of where we were, except Carl insisted I refer to the location only as “the high country of Colorado.” He explained why: “Hunters are territorial, and they have guns.” So did he: a Glock strapped to his hip, in case a large predator tried to move in on his kill. The prospect of him killing something, however, constituted a mighty if, considering this was Carl’s 40th year as an archery hunter and he had never harvested an animal with an arrow.

It was early September 2024, the second day of Colorado’s bow season. Carl, a 65-year-old house painter from Vail, held elk and deer tags good for both sexes but so far had not seen any animals. The sun’s heat felt like it does in July. Carl had dark, greasy smudges on his cheeks to avoid detection by his targets, and was dressed in a camouflage long-sleeve hoodie and beige pants. He would have been nearly impossible to spot if not for his 75-liter azure backpack, which could only be camouflaged in an ocean.

Carl started hunting, with a rifle, in 1983, drawn by the idea of filling his freezer with meat. He harvested a large buck his first day out, downvalley from Vail. Then he got a bow and never went back to bullets. He still owns a very nice rifle and knows it would improve his chances. But harvesting on its own is no longer worth the concessions in style and pride—and hasn’t been for decades.

Teig, a local electrician 24 years younger than Carl, has no problem making such concessions, even if his heart, like Carl’s, belongs to his bow. Resting in the shade, Teig was camouflaged from his ballcap—a brown flat-brim that read “Elk Hunter”—to his boots, all 6 feet and 3 inches of him. He spoke only in whispers.

Sometimes Carl and Teig hunt with other people, but mostly they go with each other. Their relationship skews toward mentor-mentee—Carl the self-deprecating sage, Teig the highly skilled understudy—owing to Carl’s experience in the mountains more than their respective hunting records. Quietly through the years, Carl had built an impressive list of conquests: he skied the Messner Couloir on Denali, riding out three nights in an ice cave at 17,000 feet; climbed the east ridge of Mount Logan, North America’s second tallest point, during a blizzard; made a first descent in Patagonia; summited three peaks in a season in Peru’s Cordillera Blanca; and kayaked the Grand Canyon.

He also survived a full avalanche burial on Vail Pass before transceivers were widely used; a thunderous slab in British Columbia that nearly washed him over a cliff—saved by a sapling that he grabbed at the last second; and a crevasse fall on Mont Blanc that left him dangling above death.

“Carl gets a lot of good days because he’s not afraid of the bad days,” says Scott Toepfer, a retired avalanche forecaster and one of his closest friends, summing up Carl’s approach to adventure.

Teig, meanwhile, grew up in the Vail Valley and started hunting as a grommet, following his dad through the forest with a rubber-band gun. He killed his first elk with a rifle when he was 12. As soon as he tried bow hunting, he says, “I caught the fever.” He found its intimacy—most shots are taken within 40 yards—“addicting. You only get one chance.”

Over 16 seasons as an archery hunter heading into 2024, Teig had harvested four elk, including a 600-pound bull that fed his family for two years. That success rate was about two and a half times the 2023 average, which hovers around ten percent in Colorado and serves as one of the discipline’s chief deterrents. Teig’s father never got into bow hunting. “He’d say, ‘No, I’m not a vegetarian,’” Teig recalls.

I had backcountry skied with Carl for years and often heard stories about his hunts, tinged with hints of hilarity. I also knew he avoided attention; allowing a reporter into his fold went against his ideology. He agreed to let me chronicle his season reluctantly.

More than simply accompanying him through the forest, I was here to see how Carl, a proud outdoorsman, self-made and successful, had lasted four decades in a sport built on results. How did he maintain his passion in the face of so much failure? And what life lessons might be buried within his futility?

Just downhill from their lunch spot, Carl and Teig made a plan in hushed tones that would take them back to camp by sunset. “I’m gonna go slow,” Carl said. “I might sit down.” “That’s fine, Carl,” Teig replied. Carl smiled. They fist bumped and tiptoed in opposite directions.

The post He’s Hunted for Elk for 40 Years but Hasn’t Killed a Single One. And That’s OK. appeared first on Outside Online.