In the past, for veteran federal employees, the weeks leading up to a potential shutdown situation have always involved a flurry of emails and meetings in preparation for a winding down of their agency. That, at least, has been the experience of an employee I spoke with at the National Institutes of Health (my former employer) who asked not to be named for fear of retribution. This time was very different, they told me: “I experienced absolutely none of that, because there’s nobody around me…I go to the office most days and it’s empty.”

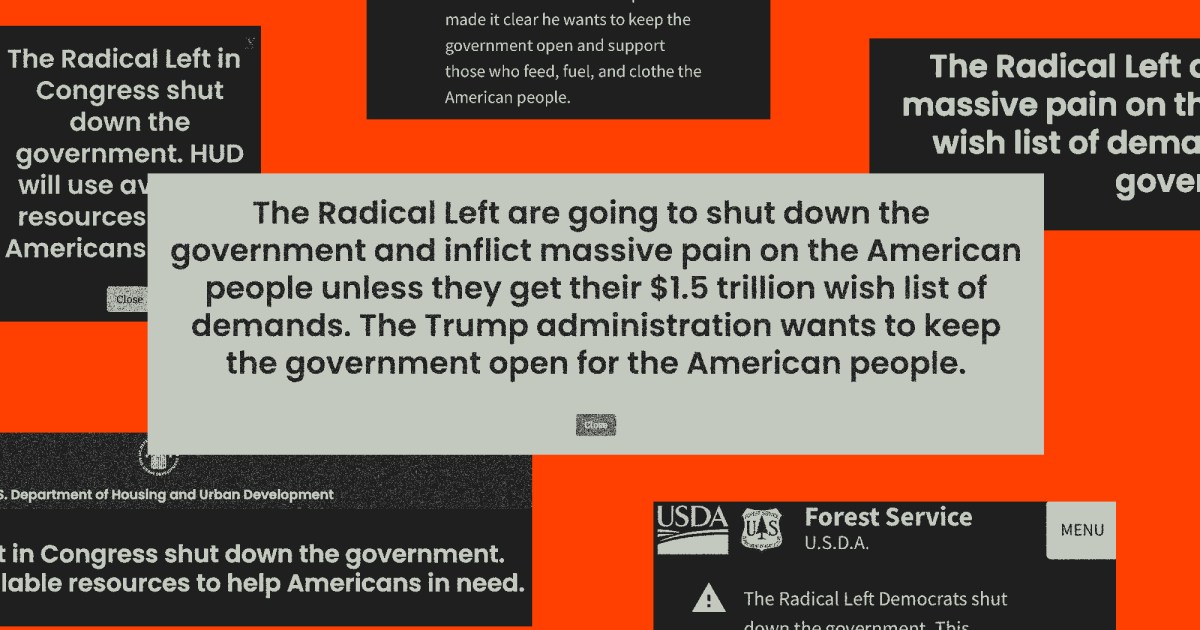

One of the few communications this employee received was an email stating that “President Trump opposes a government shutdown” and that any lapse in funding was “forced by Congressional Democrats.” Emails of this nature have been sent to employees throughout the government, in addition to some agencies instructing their staffers to set up out-of-office emails containing similar language—some employees have even reported that their automated replies were altered without their consent.

Apart from violating an apolitical ethos that runs deep within the career federal workforce, this partisan framing is a likely violation of the Hatch Act, which prohibits federal employees from engaging in political activities. “Honestly, at this point, I don’t think me or my coworkers were shocked at the ethics violations,” says a State Department employee who also asked for anonymity.

The NIH employee wasn’t particularly surprised, either, they said, but given the workforce reductions and other administration actions that have impeded their work since January, “I liked the fact that I still had the capacity for disappointment.”

The Hatch Act isn’t some small stipulation buried away in an employee handbook. Impartiality is emphasized in the ethics training that federal workers take when they start their jobs and typically re-up every two years. And it’s something career civil servants take seriously.

“I, like every other federal employee, have gone through tons of hoops and given up tons of things,” the NIH employee said. For example, when invited to give lectures at other institutions, the employee had to fill out piles of paperwork and always declined any honorarium, as many federal workers are required to do. “And that didn’t bother me. That felt correct,” the employee said.

Of the Hatch Act and related ethics stipulations, they added, “Those aren’t laws for the sake of being laws. They actually were things that were worth believing in because they prevented real conflicts of interest.”

The Trump administration’s blatant disregard of the laws and traditions governing federal communications—rules that most employees follow dutifully throughout their careers—has left some workers with a bad taste in their mouth. “Not only is it insulting to the standards we’re all supposed to abide by,” the State Department employee said, “but it’s also insulting to our intelligence.”

It furthermore has added insult to injury. A shutdown is a pause to normal operations, but for those who have remained in the federal government through rounds of layoffs and reduction-in-force deals, normal operations ended a long time ago. “I can’t do the job I was hired to do now at all…because, you know, everyone I work with was fired,” the NIH employee said.

This is true for teams across the NIH and other agencies. For much of this year, the website of the NIH institute I used to work at had a banner alert saying it was not being updated because of “reduction in workforce efforts.” Now, a new banner blames the lack of updates on the shutdown, when the truth is that the entire team that managed that website is gone.

To claim the shutdown is the cause of government dysfunction—and to blame “the Radical Left in Congress,” as the Housing and Urban Development website does—is “factually untrue,” the NIH employee said.

This is something many Americans realize, even if they don’t share front row seats with dedicated federal workers. But the pain for those workers transcends the administration’s falsehoods: “There were reasons for the rules and the norms,” the NIH employee told me. “They created a sense of legitimacy…The institution doesn’t have the legitimacy it did six months ago.”