Just a few months ago, pro-Palestinian college students around the country were getting arrested and detained by US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. But some are now challenging their detentions in court—and getting released.

Last week, Columbia University student activist Mahmoud Khalil, the first known pro-Palestinian activist arrested by ICE under the Trump administration, was let out of a Louisiana prison on bail by a federal judge who called his detainment unconstitutional. That decision followed the release of another previously detained student activist from Columbia: Mohsen Mahdawi.

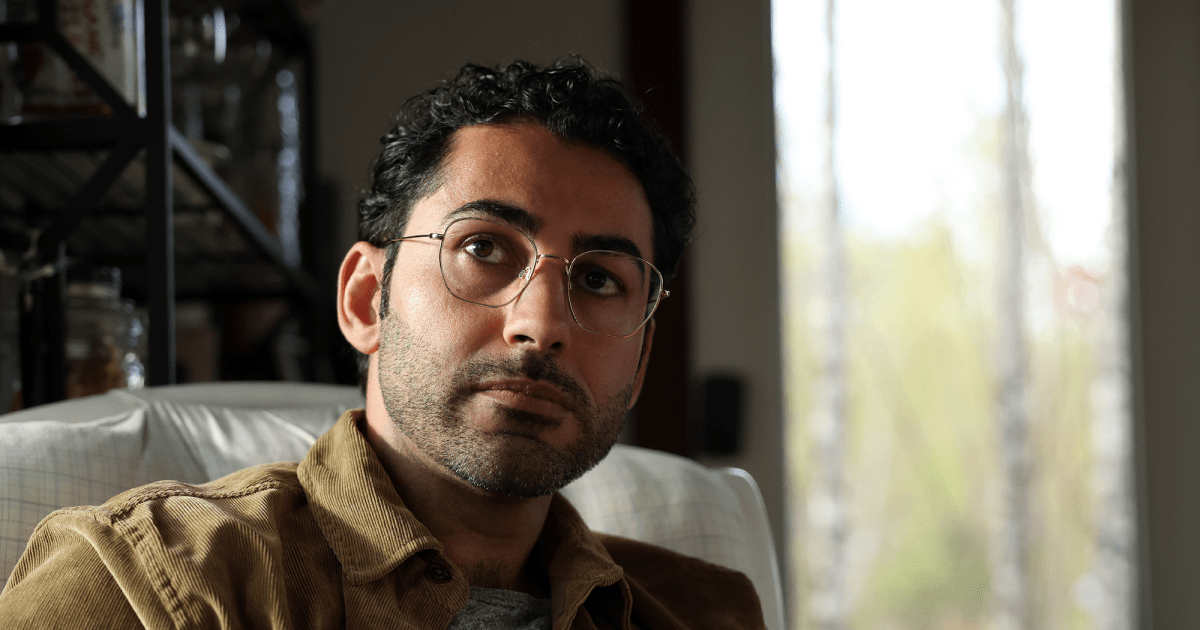

In April, Mahdawi was scheduled for an immigration interview to obtain US citizenship. But after watching what happened to Khalil, Mahdawi knew he could be handing himself over to federal agents just by showing up. “I had conflicted feelings,” he says of appearing at the immigration office. “Is this an actual interview for my citizenship that I’d been waiting for for over a year? Or is it a trap?”

Soon after Mahdawi took an oath of allegiance to the US, ICE officers surrounded and arrested him, and the Department of Homeland Security accused him of jeopardizing the country’s foreign policy interests. But Mahdawi was prepared. Through his lawyers, he quickly sued the administration over his detainment and was released on bail a couple of weeks later. He says he believes he was detained “to intimidate other students, to make an example of me.”

On this week’s More To The Story, Mahdawi sits down with host Al Letson to discuss his arrest, the accusations that Columbia’s pro-Palestinian protests made Jewish students feel unsafe on campus, and the troubling images that linger from his time growing up in a refugee camp in the West Bank.

Subscribe to Mother Jones podcasts on Apple Podcasts or your favorite podcast app.

Find More To The Story on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, iHeartRadio, Pandora, or your favorite podcast app, and don’t forget to subscribe.

This interview was edited for length and clarity. More To The Story transcripts are produced by a third-party transcription service and may contain errors. Please be aware that the official record for More To The Story is the audio.

Al Letson: You went through a really traumatic experience. I want to kind of unpack all of it. So let’s just start from the beginning. Weeks before your arrest by ICE and April, you had a feeling that something might happen when you showed up for your citizenship interview. What tipped you off?

Mohsen Mahdawi: So, Mahmoud Khalil, who is my fellow student and a friend from Columbia, he was detained on March 8th. The night Mahmoud was detained, my phone was ringing over and over and over after 3:00 A.M. It was a Saturday, so usually it takes Saturdays to meditate. And generally speaking, I ignore phone calls or when people are reaching out to me, but when I saw that my phone was basically exploding with messages and phone calls, I decided to answer. And that’s when I picked up the news that Mahmoud was detained.

And there was fear and intimidation and serious concern in the student body, everybody was encouraging me to leave the city. But at that time, I said the best course of action would be sheltering in place because most likely if I get outside of the building where I was staying, I would be also caught, kidnapped, and taken to Louisiana. And that what sets the feeling for the interview. So the moment I received the interview, I had conflicted feelings. Is this an actual interview for my citizenship that I’d been waiting for over than a year, or is it a trap?

I imagine when you got the notice that you had this interview and all of this is going on, that it feels like this can’t be a coincidence.

That’s exactly right. And I saw also what ICE agents have done with other students. For example, two students from Columbia, one PhD, and one undergrad who’s in Barnard, they went to their own apartments and dorms, and ICE agents were activated there.

The first thing I’ve done when I received this, I emailed the legal team who I was working with, and they said, “We need to wait on this.” And they too were kind of confused. “Yeah, it might be a trap, it might be a legitimate interview.” But we knew that by that time because President Trump in January, he declared that pro-Palestine students would be deported, and there was a vicious attack by the extreme pro-war, pro-Israel groups that were calling for our deportation. And they actually launched a campaign against me starting in late January, about two months before Mahmoud was arrested.

What was the mood like on campus prior to Trump’s election? Did you ever think something like this would happen, i.e., them coming to take student protesters and basically deport them all because they were just exercising their first amendment rights to free speech?

The general sense was not there to be honest with you. I did not imagine that this is coming up and I hear the threats and the promises that is being delivered by Trump. And actually, some of my friends said, “You should speed up your citizenship interview because what if he comes into presidency and then he starts deporting people?” And I thought, “Well, I can’t see it happening for students with visas, but I am a green card holder. I’ve been in this country for 10 years. I’ve seen it through ups and downs. I’ve seen the first Trump’s administration policies and way of action. I have not seen anything like this.” So it was a very low possibility on my end, but I did not see it coming this way.

What did you do to try and prevent your detainment when you had a feeling that this might be coming down the road?

A number of things. What I did, actually, this is something I learned from Palestine because I was born and raised in a refugee camp living under the apartheid system of Israel and under occupation. So I knew the best thing to do is to limit my contact, to not create routines, to not be in public spaces and to shelter in a place where nobody else except a very, very tight trusted circle. And in fact, I was sheltering in a place for a long time, for over more than 20 days I was in the same spot, I did not leave the apartment.

I also tried to reach out to Columbia to engage the senior administration telling them that, “You have encouraged us to free speech and academic freedom, all what we do here.” So I tried to engage Columbia University as well in the conversation to provide protection to me and to move me from off campus, which is I was living basically nearby campus, but on the street. If I walk outside of the building, ICE agents could detain me.

Do you feel like there was a change in the administration of Columbia or do you feel like this is kind of always who they were since you started there?

I would say that there is a betrayal to the principles and values of the university because when it came to Ukraine, for example, I was at Columbia and I saw the statements that came out from the senior administration. They even lit Law Library, which is the most significant building if you’ve been on campus, they lit it with the Ukrainian flag and they made very strong statements. They encouraged the students to speak up and they provided resources to Ukrainian students. And keep in mind, I lost many family members after October 7th, and other Palestinian students also lost family members.

When people say the protests you were a part of at Columbia were anti-Semitic and made Jewish students feel unsafe, how do you respond to that?

I would say this is a false accusation. It’s part of this whole agenda of gaslighting American people and capitalizing on the trauma that the Jewish people have from the anti-Semitism in Europe, and they’re pointing the wrong directions. There are many reasons why this can be easily refuted. First of all, I have many partners who are Israelis who see the injustice, who stand against it, and who want to see peace and justice in the region. So they cannot be anti-Semitic. They call them self-hating Jews sometimes, but they cannot be called anti-Semitic, Israelis and Jews.

The second part, I have actually wrote a paper, a long paper, over 60 pages, about envisioning a peaceful resolution in the Middle East, especially between Palestinians and Israelis. Add to all of this, I’m a person who is empathetic. I understand and I empathize with the pain and the trauma of all people. And my empathy, as I mentioned in many different interviews, extends beyond the Palestinians, my people. It extends to the Israelis and to the Jewish people. And my whole project, my whole vision, is centered on basically alleviating and relieving the suffering and the pain of the children who are innocent of any guilt. The children who deserve to live free of trauma, free of pain, free of suffering.

And I am also a Buddhist practitioner. I believe in nonviolence, I believe in empathy, I believe in alleviating suffering. So the accusations of anti-Semitism, it’s a textbook tactic to basically create more intimidation and fear and to blind people from seeing the truth. The truth is very clear, that there is a genocide in Palestine and there is an apartheid in Palestine, and America is funding it.

So going back to the process that you were going through, what’s going through your head on the morning of the citizenship interview?

I would say on the night before the citizenship interview, I actually was meditating the night before. And by that time, keep in mind I have prepared well before the interview, not only for the questions that I would be asked for the citizenship about the constitution of this country, but also I prepared that this might be a very strong possibility. So I reached out to my representatives, to the senators and the congresswoman, to house representatives, to my community tight circle. And they said, “Just keep it confidential, but this is a possibility.” I did interviews with some media telling them, “I’m a peacemaker, I’m a person who’s advocating for ending the conflict and for justice. And this is my story because if I get detained, I may not have a voice anymore.”

And I also prepared with an intelligent team of lawyers who were so prepared that at the moment I get captured or detained or with the accurate names, kidnapped, because that’s what happened, they would be able to file on the spot to prevent my transfer from here to another place. So this is all before the day off, I was thinking, “How can I be comfortable during detainment?” So what I did is I chose the suit and the shirt that are most flexible and breathable. Instead of using formal shoes that would be difficult on my feet, I chose a sneaker, a white slip-in sneaker, and I ensured that I would be comfortable, so I was hydrating and trying to just be ready for that moment.

I think it’s really important to say just really clearly for the listeners that before this interview, you didn’t come to this country without documents. You have a green card, you were documented, you were here legally, all of this stuff that happened to you should not have happened under the rule of law.

That’s exactly right. And also, I’m like if one might say a perfect immigrant. I worked in this country, I paid taxes, I learned about the laws and respected the laws, never committed a crime. And I went to the top institutions to learn basically Western education and that is what has opened my world. So to make this exception and to want to basically silence me, that’s what they wanted, and to intimidate other students, make an example of me, is really a great violation I would say, to what we have seen in this country, even to the rule of law.

Can you tell me about the arrest itself? In the back of your mind, and maybe not even the back of your mind, in the forefront of your mind, you knew that this was a possibility. So you’re heading to the interview that’s been set up with immigration. Talk me through the arrest. How did it all happen?

We entered the USCIS office, which is the immigration where my interview should take place. It was myself, the lawyer, and a friend of mine. After we arrived, within less than 10 minutes, the lobby had nobody, everybody was processed and left the office except us, just three people sitting in the lobby. And it gets so quiet to the point I looked at my lawyer and my friend, they said, “The calm before the storm.” Well, the interview took place, I answered everything as I should, and I answered the questions. And there was this moment, actually after I was quizzed on the test, before you become a citizen, you have to study 100 questions about this country and the institution.

So I answered them correctly and the agent who was interviewing me, he said, “Would you be willing to take the Pledge of Allegiance to protect and defend the constitution of this country?” And I said, “This is why I’m here, because I believe in the principles of this country. Of course, I will.” And he asked me to sign a document. So I signed the document and he said, “Just give me a few seconds.” He opened the back door and all the sudden DHS agents stormed the office and they say, “You’re under arrest.” They isolate me from my lawyer, they don’t show me any paperwork, and I give them my hands. I didn’t want to be handcuffed to my back, so I give them my hands and I say, “I’m a peaceful man. I’m not going to resist.”

And I have to give them credit because they did not make the cuffs too tight on my hands and I noticed that they were gentle. And this is something special to Vermont, that generally speaking, even if you deal with ICE agents or with police in Vermont, the culture is a little bit different. And that is when basically I was taken out directly into an unmarked SUV and that’s the moment when I was very calm. I was able to be so aware of my surrounding and I saw somebody with a phone recording and that’s when I saw him, I wanted to send a message, and I gave the V sign and I smiled.

One of the things that really struck me was something that you had talked about before, which is the revelation while being detained about following the footsteps of your family members and your elders. Can you kind of talk me through that?

I thought that I was off the hook the moment I left Palestine, and off the hook means that I’m not no longer subjected to systems of injustice and being detained unjustly and being put in prison and being persecuted just for speaking up for justice and for truth. So over the years, after my family was exiled into the West Bank into a refugee camp, my grandfather was arrested unjustly and put in prison. My father and my uncles, and recently also over the past two decades, my cousins. So when I was detained and put in a cell in a prison that was seven by 12, this is the dimension of it, I really started thinking of how did they feel my family? And I felt connected to them. And it was ironic that this is happening in the United States in a place where I first knew the experience of freedom.

I never knew what freedom is before coming to the United States. Now I am being detained for speaking about my first-hand experience, the pain, the loss, the trauma that I felt in the refugee camp. And there was this very strong image actually because there is routines in the prison. So the guard would come with a flashlight at night and they would check regularly. And how would they check? They would shine the light through the squared window in the door. And one night while I’m laying in the bunk bed, the light was so strong in my eyes, it flashed in my eyes, and with it I had a memory flashing of my uncle Abed who had permanent red eyes from the torture in Israeli prisons, and that’s when I started connecting this whole image with my uncle, with my cousins, and with my father and my grandfather.

When you were younger, you experienced some violent incidents growing up in the West Bank. Can you tell me about those and how they shaped your worldview?

So, as a child, just living in a refugee camp is a level of suffering, very tight place, almost 61 acres with about 10,000 people. You have no space to play, no space to study except in refugee schools. And it’s a very difficult experience. Add to this, the very traumatic experience during the Second Intifada. And as a child, I saw my best friend who was actually a Black Palestinian, 12 years old, his name is Hameda, was shot by an Israeli soldier and killed in front of my eyes. We were playing basketball before and basketball without having actually a basket in the street. We just like shooting over kind of an edge, and if it lands 90 degrees, we consider it that we scored. Very innocent kid. Oh, his life was taken in a second and I felt that burn inside of me. That is unjust. He shouldn’t have been killed. He’s an innocent kid.

Also, I lost my uncle September 12th, 2001 after September 11, and that’s actually was my 11th birthday. Instead of my uncle celebrating my birthday, I walked in his funeral and I saw him with blood on his beard, blood on his body. He was shot twice in the head and once in the shoulder. And for a child, this is a traumatic experience to lose somebody who you look up to. And after that, this series continues. I lost two cousins, I was shot in my leg when I was 15 years old, and the trauma of the explosions, the shooting, seeing people body parts just torn apart all over the place and skin sticking on walls where I had to peel it with my little hands when I was 12 years old, to put their bodies in plastic bags. That’s all very strong images, trauma that can live with us forever, and I feel very blessed that I was able to process this trauma and to heal from it.

Here in America, America provided me, and Vermont provided me, with the space to reprocess and to feel a little bit safe and to be able to heal from this. So those experiences you feel at rest in your stomach, you feel a rage at the beginning and anger when you see them. This is something weird to say. I’m grateful for this path of suffering because without pain and suffering, I would not understand what healing and joy is. Without this path of loss and the trauma, I may not have that strong sense of empathy to alleviate stress and the trauma. And seeing what’s happening now in the West Bank and in Gaza and even what’s happening in Iran and in Israel, it makes me just empathize with children who are going through this. Wars are not an answer to making peace.

After this long journey and everything that you’ve gone through here in the United States, do you still want to be a US citizen?

I think the United States is in a very critical stage of its life. The country is in danger. I see that. And I’m not alone. It’s every other American who is concerned about equality, was concerned about democracy. It’s a struggle for humanity. And what’s going to happen in America is going to affect the rest of the humanity. So do I want to be a citizen? I am in solidarity with people here. We’ll see what’s going to happen.

I hear you. That’s not a clear answer though. So are you saying that, listen, I wouldn’t blame you for feeling differently after everything that you’ve gone through. This is not a trick question. I’m just curious that after everything you’ve gone through, would go into Canada be better? And so I just imagine that there’s got to be this feeling of like, “Where do I call home?”

What’s the alternative? The alternative is putting my life under risk to go under apartheid system that might assassinate me, that might imprison me, that might shoot me, to live in a West Bank under the Israeli terrorist settlers who are living there and attacking Palestinian communities every day. So this is the only home actually that I’ve known when it comes to being safe and loved. And yes, I want to be a citizen in this country.

When I look at the history of this country and I think of Martin Luther King, he was imprisoned, he was treated badly, he was spied on, he was attacked. John Lewis, he was hit with a bat and he continued to be persecuted and he was imprisoned, but they did not give up on the principles, because the principles are good principles, to be honest with you. The issue is the application of those principles. What makes America great really is this diversity and this continuous momentum for struggle. And it’s a struggle some people think for racial equality. No, it’s a struggle for humanity. We all now are yearning for this equality for humanity to be seen, to be respected, and to have our freedom and our rights, and we are in this together.