The group chat lit up Jonathan Paz’s phone: Another immigration raid was happening a few blocks away. Paz took off running.

He arrived minutes later to a quiet block of auto body warehouses in Waltham, Massachusetts, where SUVs with tinted windows had surrounded a sedan and apprehended the driver, a man in his late 20s. An Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent in a balaclava and tactical vest stood in the street, talking to a 13-year-old boy who had been in the car. As Paz approached, he realized the agent was going through the boy’s phone and asking about his immigration status.

Paz, 31, is the founder of Fuerza, a volunteer group in Waltham that responds to ongoing ICE arrests. On that gray morning in May, he had been in the middle of a neighborhood patrol walk when he got the text messages. He did as he’d trained dozens of volunteers to do: He pulled out his phone and started recording, stayed a few feet from the officers, and addressed the boy. “I was telling him to relax. I was telling him to breathe,” Paz says. “I was telling him his rights—like, don’t say nothing. You’re here. You’re fine with us.”

Within minutes, the agents had driven away with the man, leaving the child alone on the sidewalk, hands in his pockets.

A handful of other volunteers were already on the scene, including Colleen Bradley-MacArthur, a Waltham city councilor, who recorded video as an agent veered his car toward where she stood on the sidewalk before telling her not to interfere.

The operation dispersed as quickly as it escalated. Within minutes, the agents had driven away with the man, leaving the child alone on the sidewalk, hands in his pockets. Volunteers walked the boy home—the man who had been detained was his dad’s friend—and suggested a pro bono lawyer who might be able to help the man, who was detained at the Plymouth County Correctional Facility. They logged the incident into the records they’ve been keeping of ICE arrests. A few days later, the event made the national news, thanks to Bradley-MacArthur’s video.

But before any of that, on the sidewalk at the scene of the arrest, Paz pulled the boy aside for a pep talk. Paz knew what it was like to see ICE detain a loved one: When he was 14, his father was deported to Bolivia and his mother followed soon after, leaving Paz and his brother in the care of an aunt. Paz went on to become a Waltham city councilor and mayoral candidate, and he now works at a tech company while spending his free time on Fuerza.

“None of this stuff is okay. I don’t want you to think this is normal,” Paz remembers saying to the boy, “but that doesn’t mean it defines you.”

Waltham, a city of 66,000 a half hour from Boston, has historically opened its arms to immigrants. A quarter of the population is foreign-born, and a fifth is Latino. A short stretch of a main drag called Moody Street features restaurants with cuisines from a dozen countries.

But lately, Paz says, it feels like his city is under siege. When I joined him on a neighborhood patrol last month, he kept an eye out for the license plates of ICE agents and flagged recent landmarks. “We had someone arrested today, I think, down the street that way,” he said, pointing down a residential block. We walked by the spot where the 13-year-old was left standing on the sidewalk, and the place where, a few days after that, a high school girl recorded officers smashing a van window to arrest a driver as she waited for the school bus.

He nodded to a sedan parked outside a warehouse. “You start picking up on the fact that there are abandoned vehicles because people had a loved one taken,” he says.

At CPAC in February, border czar Tom Homan promised, “I’m coming to Boston. I’m bringing hell with me.”

Fuerza documented more than 50 arrests in Waltham in May—likely far fewer than the actual number. The dramatic escalation wasn’t surprising. At CPAC in February, border czar Tom Homan promised, “I’m coming to Boston. I’m bringing hell with me.” A month later, on a trip to Massachusetts, Homan stopped by a Mexican restaurant on Moody Street for breakfast. No arrests were made that day, but the visit spooked employees.

It felt “like a mobster,” says Bradley-MacArthur, coming “to survey their territory.”

The sweeps in Waltham typify ICE’s crackdown across the country—one that has swept up immigrants at court houses, schools, traffic stops, and workplaces, from day laborers in Los Angeles to construction workers in Tallahassee to coffee farmers in Hawaii. ICE recently announced that federal agents arrested nearly 1,500 people across Massachusetts as part of an enforcement surge in May dubbed Operation Patriot.

Fuerza is one of countless rapid response groups that have sprung up to document arrests and warn other immigrants to stay away. In Waltham, when someone thinks they see ICE activity, they call a volunteer-staffed hotline run by a statewide immigrant rights group called LUCE. Flyers for the hotline are everywhere in Massachusetts, pinned to bulletin boards, taped to lamp posts, posted in the comments sections of neighborhood Facebook groups. The hotline receives as many as 100 calls a day, says volunteer Jaya Savita.

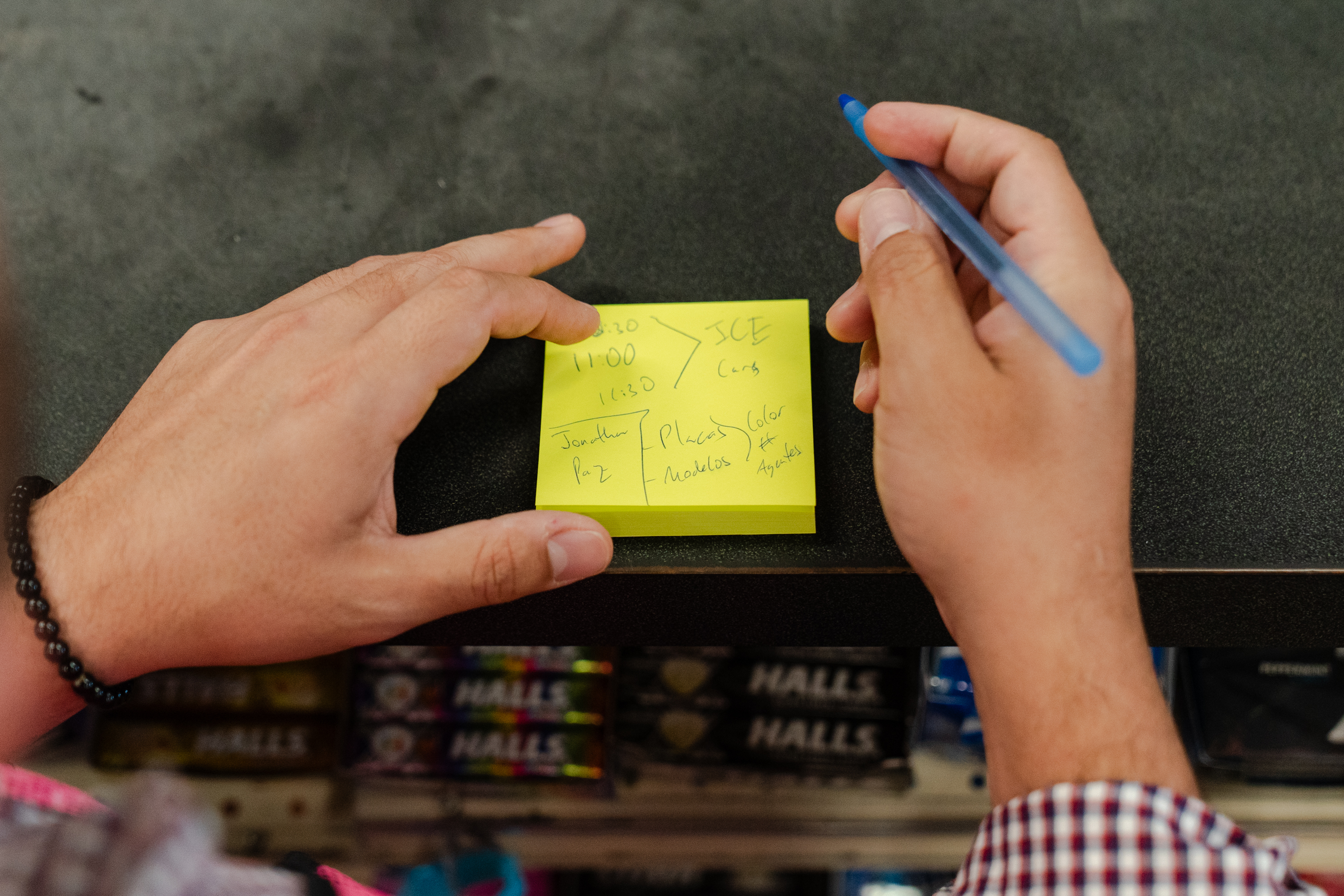

LUCE then alerts Fuerza volunteers, called “verifiers,” who go to the scene of the alleged enforcement. If the officers are indeed with ICE, Fuerza spreads the word to neighbors. Verifiers are trained to document what’s happening without interfering; they practice stepping back at least seven paces, telling officers that they’re going to record what’s going on, and asking the officers what agency they’re with. They also talk directly to those being arrested, informing them that they have the right to remain silent.

“This administration is telling a story that they’re coming after criminals. They’re not telling you that they’re taking small business owners and left a bunch of kids without their dads.”

LUCE was inspired by Siembra NC, a program in North Carolina that pioneered the volunteer-driven ICE hotline model. Siembra, which started during the first Trump presidency, has trained more than 1,200 volunteers outside of North Carolina this year, helping teach groups in Atlanta, Nashville, Phoenix, and California. Each has its own tactics. Some groups arm volunteers with loudspeakers; others do neighborhood patrols with walkie-talkies. Many, like Fuerza, also try to help the families of those who have been detained with referrals to pro bono lawyers, mental health care, and other social services.

“Hundreds and hundreds of people keep showing up to these community watch trainings,” says Marlene Martinez, Siembra’s rapid response manager. The hope, she says, is to change the narrative about ICE arrests. “This administration is telling a story that they’re coming after criminals,” she says. “They’re not telling you that they’re taking small business owners,” she adds, “and left a bunch of kids without their dads.”

The recordings serve other purposes, too. Together, they help track trends: In Waltham, the federal agents often drive Dodge Chargers with tinted windows. As is the case elsewhere, many of the arrests are in the early morning or early evening, and the agents wear balaclavas. “That’s the easiest tell,” Paz says. The masked agents are “inside the car just waiting. And it looks really—very creepy.”

The recordings also help cases get media attention. Videos in several immigration arrests that made national headlines—including the arrest of Rosane Ferreira-De Oliveira, a Brazilian mother of three in Worcester, Massachusetts—were taken by local volunteers.

One Fuerza volunteer says she wakes up at five in the morning—“when they do,” referring to ICE officers.

But the ultimate hope is that the recordings help get someone out of detention. At the scene of an arrest, “You’re like, ‘I hope they don’t do anything illegal,’” said one Waltham volunteer, who asked to go by her nickname, Nic. “And part of you is like, ‘Well, I kind of hope they do so that we can use this and get this person out.’”

A white woman who was recently laid off, Nic has turned volunteering with Fuerza into effectively a full-time job in recent weeks, doing dispatch and training other volunteers. She wakes up at five in the morning—“when they do,” she says, referring to ICE officers. Nic had never paid attention to cars, but now, she says, “I’ve learned a whole bunch of car brands.” She was among the many volunteers I spoke to who took pride in the diversity of Fuerza’s more than 120 volunteers, who include retirees, activists, soccer moms, and church groups.

Sometimes, though, the work can feel futile. Siembra co-founder Andrew Willis Garcés says he’s not aware of any recent cases in which someone was released from detention due to footage taken by a volunteer for Siembra or other similar organizations, though such evidence has been used in past cases.

“You get all this information in a video, and it’s like, well, now what?” Nic says. It’s “better than nothing, but like, how much better than nothing?”

Like any mutual aid, the movement is hard to categorize and morphing in real-time. Fuerza recently dispatched volunteers to the local food pantry in case ICE showed up. “Then we realized that the turnout was so low because people are afraid to leave their houses, so we boxed up a bunch of the food and hand-delivered it to their houses,” Bradley-MacArthur says. “We’re building the plane while we’re flying it.”

Three weeks before we spoke, the mother heard from a friend that ICE was looking for her. Ever since, she and the kids had been in hiding.

Just before Memorial Day, I received a call from a Fuerza volunteer who is known for being a connector among Waltham’s Latino community. She asked if she could put me on a three-way-call—a mother Fuerza works with was willing to talk to me. (Both women asked to not be identified.)

The mother, who is undocumented, lives in Waltham with her sons, ages 10 and 14. Years ago, the family immigrated from El Salvador, in part to seek medical care for the 14-year-old, who has a debilitating heart condition. Three weeks before we spoke, the mother heard from a friend that ICE was looking for her. Ever since, she and the kids had been in hiding. They hadn’t left the house, afraid even to take the trash out. The boys had missed weeks of school and doctor’s appointments, living off of food brought by relatives. The mother was trying to pass the time in a way that felt light for the kids, watching Superman and having pajama parties, but she could tell the boys were scared and stir crazy. They longed to go outside, to play in the park.

She prayed that President Trump would soften his heart. No somos criminales, she said in a pleading voice.

When I asked what it was like for her to see videos of ICE arrests on social media, she began to weep. She lives in fear that she’ll be next. Did she have a plan if that happened? I asked. What would happen with the kids? She admitted she didn’t know.

At this point, the volunteer apologized to me, saying she needed to stop translating for a moment. In Spanish, she explained to the mother that she works with pro bono attorneys who are helping families plan in case parents are deported. The mother needed an affidavit authorizing another caregiver to take in the kids if she’s detained, and also a form with the kids’ passport information in the event they were sent back to her in El Salvador.

In that moment, the two came up with the plan. If the mother were detained, the kids would go to their grandmother, who lives nearby. The mother relayed the pertinent information—her full name and the names of her kids, their birth dates, their grandmother’s phone number.

“Today’s the first time she’s thinking about this,” the volunteer told me later. “She didn’t have a plan because it’s happened so fast.”