I live in Vermont, 268 miles from Canada’s capital of Ottawa and 487 miles from Washington, DC, so an interesting thought experiment is: Why do I identify with the United States? I’m legally an American, of course, and Canada doesn’t need me—but those are practicalities. What I’m asking is, at least at first, a philosophical question: What does it mean in 2025 to be an American?

And it’s a question that acquired new urgency in the last week when—obscured somewhat by the Trump–Musk imbroglio—something quite fascinating happened. The president threatened to cut off much of the federal aid to California, in response to what a White House spokesman called “lunatic” state policies, most recently the fact that a transgender girl was allowed to compete in a high school track meet. In response, Gavin Newsom, governor of the most populous state in the union (and fourth-largest economy on the planet), threatened to withhold the state’s tax payments to DC. “We pay over $80 BILLION more in taxes than we get back,” he tweeted at the president. “Maybe it’s time to cut that off, @realdonaldtrump.” As one California congressman said in a letter to the president, “this targeted political vengeance is a threat to our democracy and an offense to California and every American.” Several of the contenders in last week’s New York mayoral debate made the same point. And the stakes were raised over the weekend, as an increasingly imperial president federalized the California National Guard and threatened to mobilize the Marines to quell what was essentially peaceful protest against his signature policy of mass deportation.

Until a few months ago, the question of America’s cohesion—whether it would stick together—was rarely raised. Yes, there are always simmering secession movements (there’s a Texit, and an NHExit, and the Alaskan Independence Party, which helped Sarah Palin win the mayoralty of Wasilla back in the day), but they’re always deeply fringe (and usually deeply cringe). That’s because most people could answer my initial question fairly easily, though with different emphasis. Here’s what I would say: I am an American because, beyond my citizenship, I identify with the outlines of the American idea: America was born as a radical experiment in democracy, denying the right of kings and empires to rule at a distance or without the consent of the governed, a place with full religious liberty but where no single creed ruled save the secular one of progress undergirded by science and reason.

America was not always true to those ideals—indeed, it often fell disastrously short. But that democratic process allowed for improvement and that democratic ideal guided that improvement: toward more democracy, defined as more involvement by more types of people. America, haltingly, was on a path toward becoming the first big truly multiethnic democracy the world had ever seen. As a player in that world, America had done great damage, but when the chips were furthest down—above all in the world wars of the last century—it had sided with democracy against authoritarianism. And it had—more than most places—opened its arms to those seeking what we had to offer and fleeing the tyranny we had defined ourselves against. If we had a job as citizens, it was to keep America on those tracks, indeed to accelerate its progress down those tracks.

America was born as a radical experiment in democracy, denying the right of kings and empires to rule without the consent of the governed.

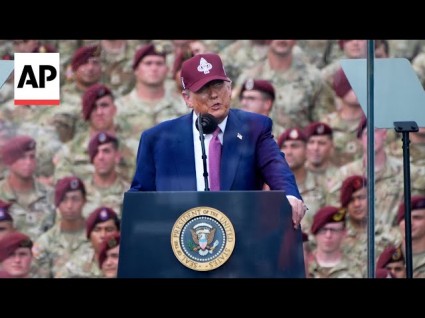

I am loath to give those ideals up, and I am fighting for them as hard as I know how (eager for No Kings day on Saturday!)—but in the past few months the new Trump administration has done its best to shred those notions. (Put them through a wood chipper, to use Elon Musk’s phrase.) We now have a king, or a president attempting to be one—not just posting pictures of himself in a crown, but ruling by fiat as best he can. He and his colleagues are doing their best to restrict the number of people who can participate in that democracy, and to restrict the control that democracy can exercise; they have done their best to remove even the evidence that our society once worked to expand participation and opportunity (the Navy has decided against naming boats for Harriet Tubman and Harvey Milk on the grounds they weren’t fierce-enough warriors); they have downgraded science and reason, insisting that the widely understood principles of climate change and vaccine science are hoaxes. Around the world they are abandoning defining commitments; the US is considering stepping back from its formal leadership of NATO, a post first held by Eisenhower in the aftermath of D-Day. We now routinely side with the big and autocratic against the small and democratic.

So—assuming as a thought experiment that we are unable to derail this new regime, and that it manages to impose its values on our government for the foreseeable future—what is it going to mean to be an American?

It’s pretty simple to figure out what it means to Trump: It’s to be a winner. We’re meant to have more. More money, more territory. A 51st state to the north, a giant frozen island protectorate to the east, a global shipping canal to the south. His urges are always the urges of toddlers; if he has a larger vision, it’s that this will yield more money for the rest of us too, but toddlers are not great at sharing. And I’d say Elon Musk and many of the Project 2025 zealots are responding to the urges of adolescent males—for “liberty” narrowly conceived, the right to do what one wants to do, unrestricted by any larger interest, the triumph of Ayn Rand in place of Ben Franklin. (Musk is clearly not a patriot—he’s got close friends in the corridors of Russian and Chinese power, and if his allegiance is to any territory, it’s probably Mars.) And of course there are Christian nationalists, responding to the high-pitched sounds of a weird hymn the rest of us (including old-school Christians) can’t really hear.

All of these are minority ideas. Powerful minorities, yes. Libertarian ideology combined with corporate money and power, especially in our age of grotesque inequity, can be overwhelming. But they aren’t ideas capable of explaining a diverse nation to itself—unlike the story I outlined above, which has more or less sustained us since the Revolution, and especially since the Depression. Trump’s and Musk’s are highly individualized stories, about personal wealth and personal salvation.

The closest I can come to making out an actual argument for what America means to MAGA comes from erstwhile (and quite good) author JD Vance, who laid it out most explicitly in his acceptance speech at the Republican convention. In it, he paid passing lip service to the idea that there were “brilliant ideas” like “the rule of law and religious liberty” that got written into our Constitution, but what he really wanted to stress was:

America is not just an idea. It is a group of people with a shared history and a common future.” When I proposed to my wife, we were in law school, and I said, Honey, I come with $120,000 worth of law school debt, and a cemetery plot…. in Eastern Kentucky is near my family’s ancestral home. And like a lot of people, we came from the mountains of Appalachia into the factories of Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. They’re very hardworking people, and they’re very good people. They’re the kind of people who would give you the shirt off their back even if they can’t afford enough to eat. And our media calls them privileged and looks down on them. But they love this country, not only because it’s a good idea, but because in their bones they know that this is their home, and it will be their children’s home, and they would die fighting to protect it. That is the source of America’s greatness.

Aside from the slightly comical roll call of swing states (apparently greatness mostly resides in states whose electors you most need), this is a kind of classic blood and soil appeal. Indeed, Vance kept returning to that graveyard:

Now in that cemetery, there are people who were born around the time of the Civil War. And if, as I hope, my wife and I are eventually laid to rest there, and our kids follow us, there will be seven generations just in that small mountain cemetery plot in eastern Kentucky. Seven generations of people who have fought for this country.

As it happens, my people have been here longer still, back to when we lived in a colony. They too came from those Appalachian hills, and they too fought in war after war—the frontier Pennsylvania home of John McKibben hosted the first Presbyterian worship service west of the Alleghenies and then became a stockade fort in the Revolution; my ancestors were fully implicated in the glories, and the Indian-fighting atrocities, of frontier America.

We now have a king, or a president attempting to be one.

But over the centuries my people moved around. America is a vast country, continental in width and almost all of it temperate, a place that made for easy mobility. My grandfather was born in China to missionaries, and he settled out West where he was the only doctor in a small shipbuilding town. His kids ended up scattered far and wide, and his grandkids even more so; I’ve made my life at the northern end of the Appalachians, in the mountains on either side of Lake Champlain. We’ve remained committed Americans, but not because we’re tied to some ancestral piece of soil; instead because we were tied to the story of our national experiment. Grandpa McKibben won a Silver Star in World War I for dragging the wounded off battlefields under intense bombardment; he’s no longer around to ask, but I don’t think it was Volkisch attachment to a piece of land that animated him. (And, since he also volunteered for World War II, I don’t need to ask what he would have thought of Vance’s friends throwing Nazi salutes.)

Vance tried a variation of his argument again a little later, when he tried to explain that he was a big believer in the Catholic concept of ordo amoris.

“[Y]ou love your family, and then you love your neighbor, and then you love your community, and then you love your fellow citizens in your own country, and then after that you can focus and prioritize the rest of the world,” he explained, calling it an “old-fashioned Christian concept.” One gets why he’d like to ground his lack of ideals in an ideal—and how freeing it would be for a ruler to operate outside a philosophical framework that could constrain or shame them. That’s what clannishness amounts to; if it’s good for your people then it’s good.

But the first and most obvious problem is moral. A few days after Vance’s attempt at exegesis, Pope Francis wrote a letter to the US bishops explaining that Vance had gotten his theology backward. “Christian love is not a concentric expansion of interests that little by little extend to other persons and groups,” he explained. “The true ordo amoris that must be promoted is that which we discover by meditating constantly on the parable of the ‘good Samaritan,’ that is, by meditating on the love that builds a fraternity open to all, without exception.”

Never fun to be corrected by the pope, but the other problem with Vance’s reasoning is simply practical. Namely, given the size and diversity of this country, is an appeal to place really sufficient to hold it together?

That is to say, as Vance is attached to the mountains of Ohio and Kentucky, so I am entirely at home in the Adirondacks and Vermont. I understand their geography, their history, their political currents, and the people who inhabit them. I feel deep connection to their flora and fauna and the way their seasons progress. I feel a certain kind of affection for the West Virginia where my mother grew up, but it’s not the same tight connection; I feel no great attachment to the black soil of the Mississippi Delta, though I honor the brave civil rights movement it helped spawn.

My link to these places is through that shared story, with which I began, but if we’re going to throw that story overboard, then Arkansas or Indiana become as Peru or the Cotswolds are to me; perfectly fine places that I’m perfectly happy to respect and admire, but not of particular deep connection. And I’m sure that Hoosiers and Arkansans feel much the same about Vermont or New York (their remove is sometimes exploited by some politicians of the heartland who disdain New Yorkers as criminals, and Californians, as we have seen, as “lunatics”).

Our vastness and complexity have always been at tension with unity. Even when America was much smaller, people’s affection for their particular place was often greater than their love for the whole, which is why the Articles of Confederation didn’t work and had to be quickly replaced by the Constitution. But if it was difficult when the country comprised the eastern seaboard, it’s much harder now. Vance and Trump can’t deport enough people to make our diversity go away; either it’s going to be something we celebrate as part of the story that makes us a whole, or it’s going to be a strain.

I’d much prefer the former. I love our vast country precisely for its geographical and cultural diversity. But if that’s not going to be our story, I’m also content to live a New England life. We’d make a perfectly sensible country, 16 million people with enough colleges and commerce and resources to get by just fine: We have the wind off the Atlantic to provide our energy, and we’ve always been skilled traders. Boston would make a fine capital, and Fenway Park is a spiritual ground zero. We’ve got Emerson and Longfellow, Thoreau and Alcott; W.E.B. Du Bois and Ethan Allen, Bernie Sanders and Big Papi, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu. We could cobble together our own story; it obviously wouldn’t be a perfect story, since this is where the oppression of indigenous North Americans had its start, and since New Englanders played their role in the slave trade—but it can boast quite rightly of everyone from William Lloyd Garrison to Susan B. Anthony to William Sloane Coffin. It has its own foodstuffs (the lobster roll, the maple sap boiling in the evaporator) and its own musicians: from James Taylor to the Dropkick Murphys. And Phish!

Our vastness and complexity have always been at tension with unity.

You could do the same exercise for, say, California, where history has been abusive to both land and people and where a breed of tech overlord currently holds too much sway, but also where they’ve built a kind of dynamism that turned the Golden State (with the help of that local industry Hollywood) into an idyll for the rest of the world. The best public college system in the history of the planet, an ever-more-successful merging of cultures from both sides of the border and both sides of the Pacific, the great parks of Big Sur and Yosemite. (And yet, with 40 million people, rewarded with the same two senators as Vermont or North Dakota.) And for that matter you could build a story for Texas, or for Florida, or the Upper Midwest, or the Plains states, or the Deep South.

It would be impoverishing to let our national links wither—I love the idea that the great national parks and wildernesses of the West are supported in some part by the ecological impulses of the crowded East, and that the civil liberties of new arrivals to the Southwest draw in some measure from the principles of early Pennsylvanians; those immigrants enrich in turn even the lives of those of us at some remove. Reflexively liberal New England is made stronger by grappling with conservative ideas from the Lone Star State, and vice versa. And Americans still speak common languages—baseball, basketball, barbecue, Beyoncé—that make life better. But those may not be enough to sustain this national project in the face of the ideological nihilism unleashed by Trump and Musk and Vance. They are taking our national tale, which is about democracy, and turning it into a tale about power, and there’s a lot of us who don’t want to live in that story.

I wrote a book about a Vermont secession once. It was a mostly comic novel, but I was impressed with the number of neighbors who resonated with the idea. That was in the first Trump years, and I said when I was interviewed about it: “I don’t think we should secede. But ask me again if there’s a second Trump administration.” And now there is a second Trump reign, far more militant than the first, whose main task seems to be disposing of the story that knit this vast country tenuously together. Trump’s been increasingly clear that he wants to kill off FEMA, the system that lets (temporarily) intact parts of the nation bail out those parts in distress: “I say you don’t need FEMA, you need a good state government,” he declared recently. There are still some practical things that link us—above all Social Security, which people have spent lifetimes paying into and can’t afford to walk away from. But it’s now unclear how long MAGA will let Social Security survive—and in a congenial breakup there’s no reason it shouldn’t be part of the settlement.

I still think our national story is worth fighting for. And I can imagine ways we come together to write new chapters. For instance, in the rapid heating of the planet we face an external threat as great as any war, and a national project to move to clean energy could be as exhilarating as the moonshot of the 1960s. It takes advantage of our scientific prowess, and it works into both liberal and conservative ideas of the good life: If your red-state home is your well-defended castle, why wouldn’t you want a bunch of solar panels on the roof? But fossil fuel money has corrupted this administration, and it feels far more likely that a clean energy Apollo project is going to be China’s story, not ours.

Maybe we’ll figure out something else to bring us back together. The American idea is worth fighting for. But not indefinitely. It’s possible we may honor it best by remembering that its early chapters were written by relatively small numbers of people in a relatively small place, and that just maybe we’ve outgrown each other.