Why is the incidence of side effects from statins so low in clinical trials while appearing to be so high in the real world?

“There is now overwhelming evidence to support reducing LDL-C (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol)”—so-called bad cholesterol—to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD),” the number one killer of men and women. So, why is adherence to cholesterol-lowering statin drug therapy such “a major challenge worldwide”? Researchers found “that the majority of studies reported that at least 40%, and as much as 80%, of patients did not comply fully with statin treatment recommendations.” Three-quarters of patients may flat out stop taking them, and almost 90 percent may discontinue treatment altogether.

When asked why they stopped taking the pills, most “former statin users or discontinuers…cited muscle pain, a side effect, as the primary reason…” “SAMSs”—statin-associated muscle symptoms—“are by far the most prevalent and important adverse event, with up to 72% of all statin adverse events being muscle-related.” Taking coenzyme Q10 supplements as a treatment for statin-associated muscle symptoms was a good idea in theory, but they don’t appear to help. Normally, side-effect symptoms go away when you stop the drug but can sometimes linger for a year or more. There is “growing evidence that statin intolerance is predominantly psychosocial, not pharmacological.” Really? It may be mostly just in people’s heads?

“Statins have developed a bad reputation with the public, a phenomenon driven largely by proliferation on the Internet of bizarre and unscientific but seemingly persuasive criticism of these drugs.” “Does Googling lead to statin intolerance?” But people have stopped taking statins for decades before there even was an Internet. What kinds of data have doctors suggested that patients are falsely “misattribut[ing] normal aches and pains to be statin side effects”?

Well, if you take people who claim to have statin-related muscle pain and randomize them back and forth between statins and an identical-looking placebo in three-week blocks, they can’t tell whether they’re getting the real drug or the sugar pill. The problem with that study, though, is that it may take months not only to develop statin-induced muscle pain, but months before it goes away, so no wonder three weeks on and three weeks off may not be long enough for the participants to discern which is which.

However, these data are more convincing: Ten thousand people were randomized to a statin or a sugar pill for a few years, but so many more people were dying in the sugar pill group that the study had to be stopped prematurely. So then everyone was offered the statin, and the researchers noted that there was “no excess of reports of muscle-related AEs” (adverse effects) among patients assigned to the statin over those assigned to the placebo. But when the placebo phase was over and the people knew they were on a statin, they went on to report more muscle side effects than those who knew they weren’t taking the statin. “These analyses illustrate the so-called nocebo effect,” which is akin to the opposite of the placebo effect.

Placebo effects are positive consequences falsely attributed to a treatment, whereas nocebo effects are negative consequences falsely attributed to a treatment, as was evidently seen here. There was an excess rate of muscle-related adverse effects reported only when patients and their doctors were aware that statin therapy was being used, and not when its use was concealed. The researchers hope “these results will help assure both physicians and patients that most AEs associated with statins are not causally related to use of the drug and should help counter…exaggerated claims about statin-related side effects.”

These are the kinds of results from “placebo-controlled randomised trials [that] have shown definitively that almost all of the symptomatic adverse events that are attributed to statin therapy in routine practice are not actually caused by it (ie, they represent misattribution.)” Now, “only a few patients will believe that their SAMS are of psychogenic origin” and just in their head, but their denial may have “deadly consequences.” Indeed, “discontinuing statin treatment may be a life-threatening mistake.”

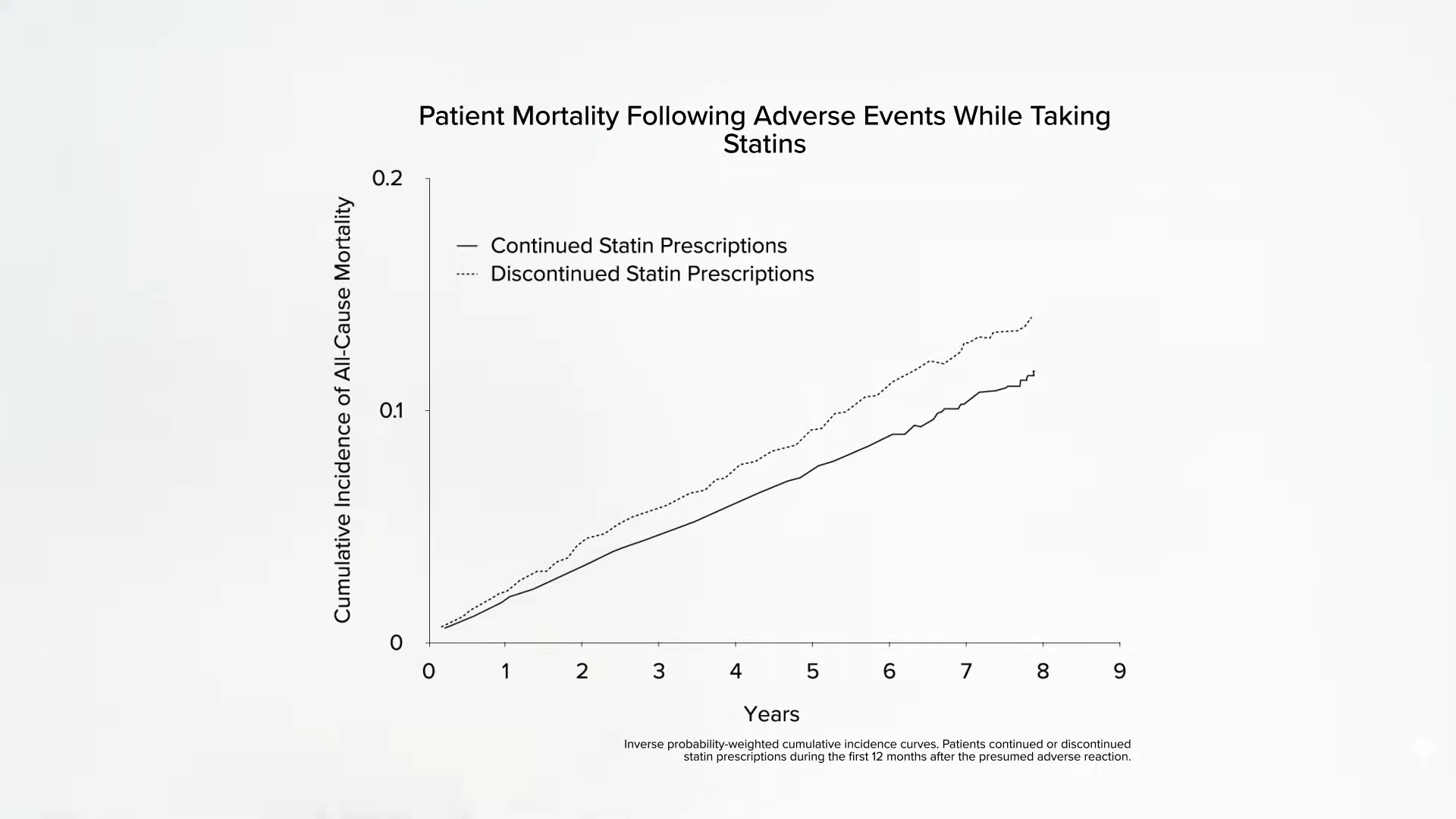

Below and at 4:46 in my video How Common Are Muscle Side Effects from Statins?, you can see the mortality of those who stopped their statins after having a possible adverse reaction compared to those who stuck with them. This translates into about “1 excess death for every 83 patients who discontinued treatment” within a four-year period. So, when there are media reports about statin side effects and people stop taking them, this could “result in thousands of fatal and disabling heart attacks and strokes, which would otherwise have been avoided. Seldom in the history of modern therapeutics have the substantial proven benefits of a treatment been compromised to such an extent by serious misrepresentations of the evidence for its safety.” But is it a misrepresentation to suggest “that statin therapy causes side-effects in up to one fifth of patients”? That is what is seen in clinical practice; between 10 to 25 percent of patients placed on statins complain of muscle problems. However, because we don’t see anywhere near those kinds of numbers in controlled trials, patients are accused of being confused. Why is the incidence of side effects from statins so low in clinical trials while appearing to be so high in the real world?

Take this meta-analysis of clinical trials, for example: It found muscle problems not in 1 in 5 patients, but only 1 in 2,000. Should everyone over a certain age be on statins? Not surprisingly, every one of those trials was funded by statin manufacturers themselves. So, for example, “how could the statin RCTs [randomized controlled trials] miss detecting mild statin-related muscle adverse side effects such as myalgia [muscle pain]? By not asking. A review of 44 statin RCTs reveals that only 1 directly asked about muscle-related adverse effects.” So, are the vast majority of side effects just being missed in all these trials, or are the vast majority of side effects seen in clinical practice just a figment of patients’ imagination? The bottom line is we don’t know, but there is certainly an urgent need to figure it out.