For kids like me, who grew up in the 1960s and ’70s, comics were a big deal. Our media landscape otherwise consisted mainly of books and records, commercial radio, and, in my family’s case, a small black-and-white TV with a coat hanger antenna that got four staticky channels. So we periodically raided our piggy banks and headed to the Stop-N-Go for candy and comics. My favorite was Richie Rich.

Richie was wildly popular, a brave and generous little fellow with unfathomably wealthy parents. He’s 9 or 10 years old in the comics, with a signature outfit consisting of white booties, blue shorts, a black jacket, and a white shirt with a big red bowtie. (He’s a teenager, with outfits less Little Lord Fauntleroy, in the 1980s cartoon series—ditto the 1994 Macaulay Culkin movie.)

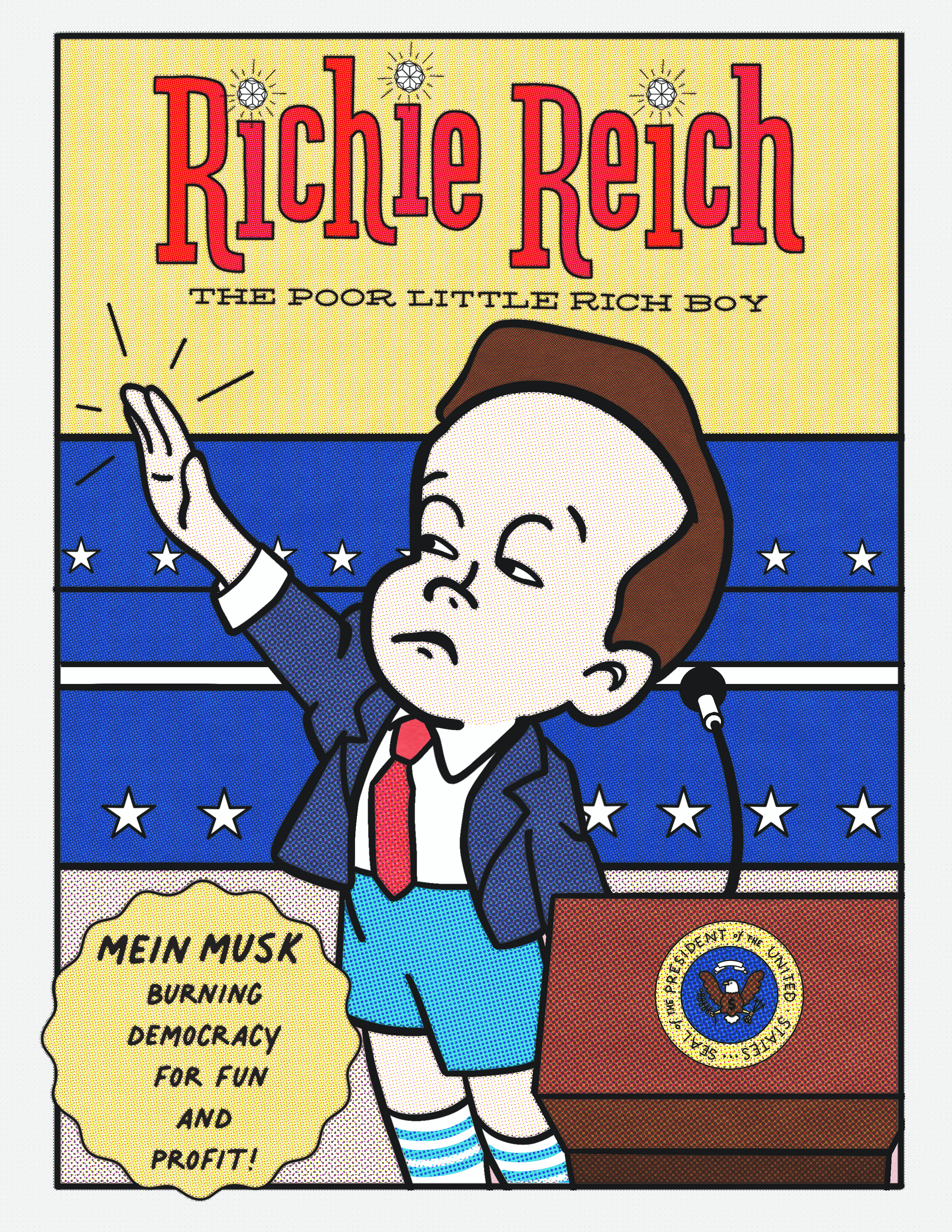

Had someone compared you to Richie back in the day, you might have thanked them. After all, he used his vast wealth for good. But Richie’s reputation has fallen upon hard times. “We all knew Trump was richie rich scumbag,” one Bluesky user wrote in March. Another posted, in reference to the Virginia governor and Trump sycophant Glenn Youngkin: “‘Richie Rich’ Youngkin (R), thinks poor people should just fucking stay poor.” A third circulated a parody comic book cover, “Richie Reich,” featuring a dour Musk/Richie hybrid doing the Nazi salute. It got more than 1,100 likes.

“Richie is so misunderstood,” laments 30-year-old news producer Jonny Harvey, whose late grandfather, Leon, along with brothers Alfred and Robert, churned out hundreds of issues of Richie Rich on their family-friendly Harvey Comics imprint from 1960 through 1982—with an encore from 1986 to 1989, when the company was sold—in addition to titles like Little Audrey and Casper the Friendly Ghost.

“I think people believe he’s this spoiled rich kid,” says Harvey, who is working on a documentary about the late family business. “Because of the blond hair, because he was the son of a multimillionaire, people make that [Trump] comparison. And there couldn’t be anything further from that.”

Something clearly has shifted in our culture that we would so defame this icon of upper-crust benevolence. As a journalist who covers inequality and the author of a book, Jackpot, about the American wealth fantasy run amok, I decided it was time to revisit Richie to try to understand how economic changes since his heyday might account for the transformation. As it turns out, there are important lessons here for grownups, even if you’ve never heard of “the poor little rich boy.”

The Richie comics, in retrospect, are wildly incongruous. Richie’s family (much like Trump’s) is comically ostentatious. His mom is a jewel-laden socialite, his dad some sort of industrialist. They have swimming pools filled with cash, piles of gleaming gemstones, safes swollen to bursting, and driveways paved with gold bars—not to mention monogrammed ships and planes and swank mansions. The “help” includes butler Cadbury, robot maid Irona, and Bascomb, a chauffeur who shuttles Richie around in a stretch limo. Their dog, Dollar, has dollar signs for spots.

It’s all quite over the top, and that’s part of the appeal. Billionaire and former Dallas Mavericks majority owner Mark Cuban, raised in a middle-class Pittsburgh family, “loved, loved, loved Richie Rich,” he told me via email. “Watching the cartoon was like driving around wealthy neighborhoods, dreaming of one day being able to afford one of the palatial homes I never thought I would ever even walk inside.”

Yet Richie is no snob. His endless money is leavened by courage, loyalty, and sheer goodness. Despite his vast fortune, he steers clear of the trust-fund kids, opting instead to share his adventures with public school pals. Richie’s besties, Freckles and Pee-Wee Friendly, basically live in a shack. “It was so funny,” says Angelo DeCesare, who wrote and drew Richie for Harvey Comics from 1978 to 1980. “It looked like this beat-up old thing with boards. They really made them poor!” Gloria Glad, Richie’s sweetheart, is the proverbial middle-class girl next door.

Plots typically involved Richie using his limitless resources to bail out a friend, help solve somebody’s problem, or foil the bad guys forever scheming to steal his family’s wealth. In a paper, York University marketing professor Russell Belk summarized one 1966 story like this: “To keep his girlfriend Gloria’s father from being transferred out of town, Richie Rich buys a hot dog factory for $500,000 and has her father made general manager. The man Richie outbids for the plant is his father, who was buying it as a gift for Richie’s next birthday.”

The Harvey neighborhood crew includes a Black kid—quite the rarity in mainstream comics back then, though race is never referenced: Tiny’s distinguishing trait is his diminutive stature. “It was a way of showing that we’re all part of the same neighborhood, that we all have the same aspirations…that we all can have fun together,” Kathy Jackson, a professor of media at Virginia Wesleyan University, told Jonny Harvey in an interview for his film. “Certainly, in the 1960s, in the age of civil rights, that had important ramifications.”

Most of Harvey’s founders, artists, and writers were first- or second-generation Jewish immigrants, more than a little familiar with ethnic bigotry. Their mission was to sell comics by creating stories that appealed to kids, encouraged them to read, and imparted good values along the way.

Richie would be appalled by the thought that “the fundamental weakness of Western civilization is empathy,” as Elon Musk told Joe Rogan in February. He would never, as Musk did on X, brag about a weekend spent “feeding USAID into a wood chipper.” Nor would he terrorize federal workers or seek Medicaid reductions to facilitate tax cuts for his family. He wouldn’t slash research funding, either—Richie loves scientists and inventors. He’d be inclined to build them new, cutting-edge labs—and gleaming hospitals for the sick, and cozy abodes for the unhoused.

Because Richie Rich is not an asshole.

He is, alas, entirely fictional. “There was no such person like that in the world, who had that kind of money and would use it in the way Richie did,” DeCesare told me. To longtime Harvey Comics editor Sid Jacobson, “Richie was his idealized fantasy of what he really wished the wealthy would be; they would be kind,” says son Seth Jacobson, 67, who remembers hanging out with his late father’s team at their offices in Manhattan’s old Gulf and Western Building. “My dad was a diehard Democrat,” he recalls. “He wanted taxes to be higher for the rich and the upper middle class. He wanted universal health coverage.”

Some Richie characters were more in sync with the Mar-a-Lago crowd, like Reginald Van Dough, Richie’s greedy, scheming cousin, and Mayda Munny, a snooty social climber who is desperate to woo Richie away from Gloria but inevitably fails because Gloria loves Richie despite his money, not because of it. “Those comics were very moral. That’s what I liked about them,” says DeCesare. “Reggie was a jerk. The idea was to be more like Richie. Be generous, kind, have empathy for your fellow human beings. Reggie was presented as the guy who always got his comeuppance.”

Ideally, children are encouraged to share and tell the truth—and to care about others. As we grow up, some people continue to embrace those values. Others clearly don’t. As for Richie’s parents, the question of what it might take to amass and protect such riches or who may have been exploited in the process is never explored. Did Mr. Rich, like even the “good billionaire” Warren Buffett, have vast holdings in polluting industries or take advantage of obscure (if scandalously legal) tax avoidance strategies? We’ll never know. Richie exists in a realm free of adult politics, unscathed by what one wealthy Silicon Valley denizen described to me as the “blasé weirdness” experienced by the heirs to vast fortunes—think Succession. (“My wife and I are doing our best for that not to happen,” Cuban told me. “I hope my kids are more like Richie.”)

The values Richie embodied, and our notion of noblesse oblige—the duty of society’s richest to behave with honor, generosity, and responsibility toward those with less—have waned in tandem with a staggering rise in wealth inequality. In 1960, if your salary exceeded $60,000, every additional dollar was taxed at a rate ranging from 71 percent to 91 percent. This helped keep our financial differences in check. But the tax cuts signed by President Ronald Reagan during the 1980s chopped the top bracket from 70 percent to 28 percent. Two years after he left office, Congress enabled a type of trust—by accident, the lawyer credited with inventing it told me—that America’s dynasties now use routinely to transfer vast fortunes, often billions of dollars, to offspring without paying a dime of inheritance tax.

Since Richie’s heyday, we’ve also witnessed the rise of the zero-sum mindset embodied by Trump and his minions. Namely, the idea that every transaction has a winner and a loser—and you do not want to lose. This ethos is now standard operating procedure for a subset of the superrich, compelling ultrawealthy parents to bribe and cheat their children’s way into elite colleges, as revealed in the 2019 scandal dubbed Operation Varsity Blues. It also helps explain why more than 84 percent of that year’s incoming college freshmen—whose collective top priority in 1969 was “developing a meaningful philosophy of life”—selected as their new No. 1 goal: “being very well off financially.”

A uniting myth of America for scrappers and strivers and immigrants is that of a land of opportunity, despite the bigotry that has pervaded our laws and culture. (Leon Harvey would have excelled in advertising, grandson Jonny told me, “but Jewish sons of Jewish immigrants mostly could not get the advertising jobs.”) The distribution of wealth in Richie’s day was by no means egalitarian, but it was markedly more so than today. The notion of a child of superrich parents attending public schools and mixing with poor and middle-income kids was less laughable in 1965, when the pay ratio of CEOs to typical workers at the nation’s 350 largest companies was 21 to 1. By 2019, the ratio had soared to 320 to 1.

Such vast resource differences contribute to what social scientists call “income segregation,” and I like to call “wealth flight.” “The things that people can afford tend to dictate the spaces that they inhabit,” explains Cornell sociologist Kendra Bischoff, who studies the phenomenon in collaboration with Stanford’s Sean Reardon. Rising inequality increases “the spatial separation of people of different incomes,” she told me. When parents opt into private schools, elite sports leagues, and other exclusive activities for their children, “those are the kinds of structural conditions that lead kids to be a lot less likely to hang out with each other,” and that lack of exposure very plausibly “limits their understanding of the world and decreases empathy for people who are different than them.”

There’s that word again—the one that, in the Trumpian mindset, belies weakness. Indeed, there’s good evidence that people of higher socioeconomic status tend to be less empathetic than their lower-status counterparts. “We find that people who are relatively well-off are less likely to orient to others in social environments,” says Paul Piff, a psychologist who studies wealth and behavior at the University of California, Irvine. What’s more, he says, “upper-class individuals show—both explicitly, they talk about it, and physiologically—reduced signs of compassion, less sympathy. They’re less moved by the needs of others.”

Who’s to know if hoarding money makes some people callous or whether less-empathetic people are simply more prone to pursuing materialistic aims? Cuban restated a theory I’ve heard numerous times, that great wealth merely amplifies a person’s character: If you’re a Reginald sans dough, you’ll end up a Reginald Van Dough. But “if you were nice and caring” before you hit the jackpot, you’ll remain a good person—and have more resources to do good. “Where I think people deviate from that is during the grind to make money—to get to having more than you ever dreamed of,” Cuban says. “That grind is filled with uncertainty for all those not born wealthy. That’s where you focus on your company, often to the exclusion of others. Families. Relationships.”

The ramifications of America’s wealth divide have grown clearer as the Trump regime lays waste to agencies and programs that the families of Richie’s friends might have relied upon and seeks to privatize federal services and enact more tax breaks for the wealthiest 0.01 percent—a group who began this year with an average of $938 million in estimated household assets, and whose share of the nation’s overall wealth has more than quadrupled since 1976, even as the middle class’s share has dwindled.

Richie Rich was a good egg, if a Fabergé one. But today, as America’s wealthiest have fallen in line behind the most egregiously materialistic human being ever to occupy the Oval Office, Richie seems like an anachronism. Remember that Gulf and Western Building where Harvey Comics once had its offices? In the mid-1990s it was acquired by a consortium that included a certain New York City real estate developer. Now it’s the Trump International Hotel and Tower.

The irony, as they say, is rich.