Ray Zahab first noticed that something was wrong with his body in the spring of 2022. “I just started to feel like shit,” he told me, chuckling. The Canadian ultrarunner was 54, and he felt like his body was breaking down. Even his warm up runs began to feel grueling. He was constantly out of breath, napping several times a day, and struggling with severe brain fog. “I felt like I had wool in my head,” he said. He wondered if he was nearing the end of his career.

Was this just what aging felt like, or was something worse going on?

Zahab had spent the last two decades crossing some of the most inhospitable environments on Earth. He’s best known for running over 4,600 miles across the Sahara Desert in 2007, becoming—with partners Kevin Lin and Charlie Engle—the first runners to do so. But if you name an extremely hot or cold place, chances are, Zahab’s crossed it. The deserts of Atacama, Namib, Patagonia, Gobi, and Death Valley. The frozen tundras of Kamchatka, Baffin Island, Antarctica, and Siberia.

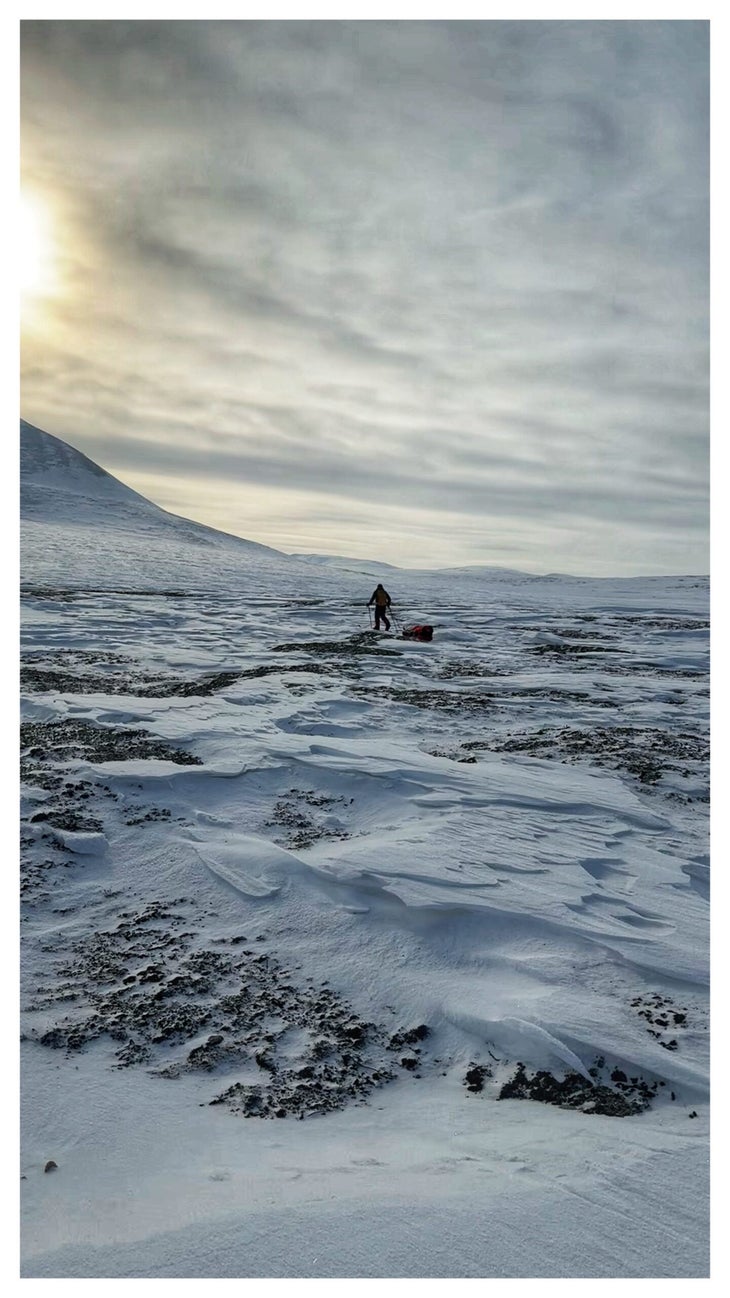

Early in 2022, Zahab and longtime expedition partner Kevin Vallely were stymied while attempting an unsupported crossing of Ellesmere, a 500-mile-long Canadian island in the Arctic Circle (and one of the northernmost land masses on the planet). “It was clear after starting northward that the snow conditions were going to make it nearly impossible to pull our heavy sleds,” Zahab said. The men made poor progress, trudging directly into a brutal wind, and Vallely ended up with a condition known as “caribou lung,” which Zahab described as “frostbite of the lining of the lungs.” They soon threw in the towel.

Now, after failure on Ellesmere, Zahab’s body was failing him, too. Doctors ran tests, and knew that something was wrong—his red blood cell count was severely depleted—but for several months, they couldn’t give Zahab a diagnosis. “I thought maybe I had long COVID, or parasites left over from a past expedition,” Zahab told me. “I wondered if I was maybe just getting older.”

When the results finally came in, they were worse than he’d imagined.

Zahab had a rare form of lymphoma, a blood cancer, in his bone marrow. He’d caught it early, and his prognosis was good, but for an extreme endurance athlete like Zahab, already in his mid-50s, it could mean the end of a career.

“My doctor was like, ‘Good news. We caught this. We don’t think you’re going to die. Bad news is there’s no cure for what you got.’”

But Zahab dove into chemotherapy with the same mentality he took into his expeditions. “I had the right, if you will, to sit on the couch, binge Netflix, and just try to make it through the next six months of treatment,” he said. “But I wanted to fight it.”

Each month, Zahab went for a few days of chemo and monoclonal therapy. “I would come home, and I’d be sick as a dog for two days,” he recalled. But as soon as he was able, he’d force himself to get up and out, pushing himself little by little. “I’d say, ‘Ok, I’m going to walk a mile one day. The next day I’d jog a mile. Then I’d get myself as fit as I could over a 10-day period, and I’d go away for a week or so to do something personally challenging, whatever that might be for me at the time.”

In between chemotherapy sessions, Zahab ran 30 miles in the Mojave Desert with his daughter. After another session, he crossed a valley in Baffin Island with friends. During another chemo break, he went to the Atacama Desert.

These trips were small potatoes compared to his usual expeditions, but they kept his spirits up. “I did these things, not to prove that I could,” Zahab said, “but to try and get myself as fit and stoked and full of life as possible before each round of chemo. I’m reminding myself that I’m alive, right?”

Zahab Returns to the Arctic

After six months of chemotherapy, Zahab was in remission. But throughout his treatments, Ellesmere Island never left his mind. And this March, almost three years after their failure in 2022, he and Vallely returned to the frozen island.

They first crossed the island on snowmobiles, burying two caches of supplies, then set out from Eureka, a research base, to ski over 300 miles to the town of Grise Fiord.

The men trudged through blizzards, across frozen sea and land, dragging 150-pound sleds behind them. “The surface of the snow was jagged, like little daggers,” Zahab recalled. “It felt like pulling something across sandpaper.” They encountered temperatures as low as -112 degrees Fahrenheit with windchill, and winds up to 60 miles an hour. “We almost never saw a morning that was warmer than -22 Fahrenheit,” Zahab told me. Zahab’s tracker suggested the men climbed somewhere between 30,000 and 40,000 vertical feet, hauling their sleds up and down steep dunes of frozen snow known as sastrugi, and endless rolling climbs overland.

When the men arrived and set up camp each night, all of their gear was so cold that touching anything was risky. “You touch the sleeping mat, it’ll give you frostbite,” Zahab recalled. “You touch the air inflation bladder for the sleeping mat, it’ll give you frostbite. Everything was so frozen that I could barely feel my hands.” Zahab got frostbite on his fingertips just from setting up camp inside the tent.

At night, they staked down their tent with custom-made footlong titanium stakes, double-walling it and burying the fly deep in the snow so it wouldn’t blow away. Polar bears were a constant threat. They staked out a wire fence around their campsites on the ice, tied to shotgun blanks that would fire if bears tripped the line. They slept with neck gaiters over their face, so that the moisture of their breath wouldn’t freeze their sleeping bags.

The men packed 7,000 calories a day, “but we were burning through it like it was nothing,” Zahab said. Their kit included six liters of olive oil, frozen solid into ice cubes, which they sucked on as they walked to keep their energy up. (By the end of the expedition, they’d become so adapted to the cold that when the temperatures crested -20°C—which was rare—they felt so warm that they stripped down to their long underwear.)

After 28 days they finally reached Grise Fiord, becoming one of the few to have ever crossed Ellesmere Island overland. “Money, time, cancer, planning, training, everything, it all paid off,” Zahab said.

“I Get to Live”

Zahab, who has a side career as a professional speaker and also founded a youth nonprofit, Impossible2Possible, is a walking embodiment of the power of positivity. But he wasn’t always this way. Until his early thirties, Zahab was an overweight, pack-a-day smoker. He went from never having run a race in his life, to setting speed and distance records in some of the most extreme environments on the planet, all after turning 40.

“For the first half of my life, I talked myself out of doing things because I was afraid of what might happen, or failing, or what others would think,” he said. “In the second half, I decided I was going to make decisions for myself. You never know how many days you’ve got left.”

Cancer, he says, taught him that “every moment you have is something to be celebrated.”

“There was this moment during chemotherapy where I decided that I was going to continue to try,” he recalled. “To do whatever I could do to keep living my life as I had before. The cancer wasn’t going to own me. I was going to own it.”

Today, Zahab is 56, and says he’s in the best shape of his life, but eventually, his cancer may very well return. He remains in remission, but the lymphoma is in his bone marrow, and there is no cure. This doesn’t faze him.

“I don’t even think about it,” he told me. “Let’s say it comes back in a few years… What am I going to do? I can spend my time worrying about that, or I can spend it celebrating. I get to wake up every single day and make an awesome espresso. I get to go see my kids. I get to run, ski, or paddle somewhere. I get to go trail running with my wife.”

“Right now, I get to live. Why not focus on that?”

The post Two Longtime Friends Cross Frozen Arctic Island After Years of Setbacks and Cancer appeared first on Outside Online.