Back in 2012, an evolutionary anthropologist named Herman Pontzer published some baffling data from his time among the Hadza, a group of hunter-gatherers in Tanzania. Using a sophisticated technique called the “doubly labeled water” method, he measured the daily calorie burn in 30 Hadza adults, and compared it with similar data from the U.S., Europe, and elsewhere. The surprise: it was more or less the same.

Obesity rates in developed countries are disturbingly high, and a seemingly obvious culprit is that we don’t have to move around as much as our ancestors did. But Pontzer’s data suggested that we burn just as many calories driving to the store and lying on the sofa as the Hadza do digging tubers or tracking warthogs. Data from other populations supported this claim. This led Pontzer to propose what has become known as the “constrained energy model”: when you burn calories by, say, running a mile, your body responds by finding ways of saving calories in other ways.

Pontzer’s idea has important implications for how we think about topics like weight loss and the health impacts of large volumes of exercise, and scientists have been debating it ever since. He and his Duke University colleague Eric Trexler have a new paper out in Current Biology that weighs the current evidence. The paper adds some new wrinkles about where the calories go, apparent differences between endurance and resistance exercise, and the role played by your diet.

Is Energy Really “Constrained”?

The strongest version of Pontzer’s claim is that when you burn 100 calories exercising, your body finds a way of saving 100 calories—that is, that compensation is 100 percent effective. Perhaps you find yourself spending a little more time lying on the sofa instead of doing chores around the house; or perhaps the adaptations take place unconsciously, as your body skimps on things like cellular repair and immune function.

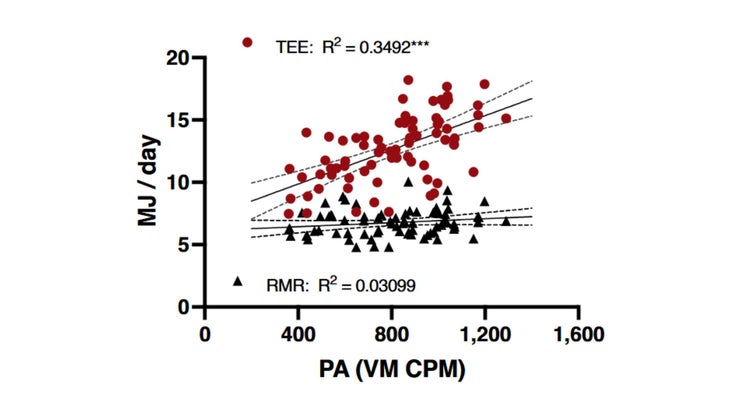

That’s what the Hadza data seemed to suggest, but not everyone is convinced. Back in October, a research team led by Kristen Howard and Kevin Davy of Virginia Tech and John Speakman of the University of Aberdeen published data from 75 volunteers between the ages of 18 and 63 who reported walking or running an average of 32 miles per week, with a range between 0 and 80 miles. Using the doubly labeled water technique, they found the following relationship between total daily calorie burn (in megajoules per day) and daily physical activity (PA, as measured with an accelerometer):

The red circles show total energy expenditure, with the relationship you’d expect: the more exercise you do, the more calories you burn. The black triangles show resting metabolic rate, which is how quickly you burn calories while lying around doing nothing. That line is flat, showing no evidence that those who exercise more are saving calories by reducing their resting metabolic rate.

To Howard and her colleagues, this graph shows that the constrained model is wrong. Instead, energy expenditure from exercise must be “additive,” contributing directly to your overall calorie burn. But Pontzer and Trexler’s new paper argues that this interpretation isn’t justified. The relationship between exercise and calorie burn in Howard’s and other datasets shows that energy compensation isn’t 100 percent. But there might still be a lesser degree of compensation going on, Pontzer says: if you burn 100 calories exercising, your total energy burn might only increase by 90 calories, or 50, or 10. That’s still compensation.

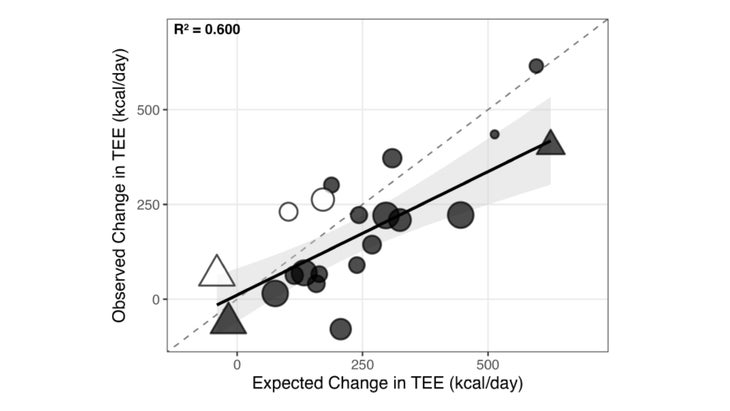

Pontzler and Trexler pool the results of 14 studies with 450 participants to show that, on average, when people start exercising, they burn fewer calories than you would expect based on how much exercise they’re doing. Here’s the key graph:

The dashed line represents a purely additive model where there’s no compensation: burning 100 exercise calories adds 100 calories to your overall calorie burn. But the solid line corresponding to the best fit through the data points falls below that dashed line, indicating that people who exercise a lot don’t increase their total energy burn by as much as you’d expect. In other words, at least some compensation is happening—but judging from that graph, it’s a modest amount, far from the horizontal line that would correspond to 100 percent.

Why Your Diet Matters

There are some additional nuances in the graph above. The data points indicated with circles show studies where subjects were allowed to eat whatever they wanted; the triangles show studies where there was some form of dietary restriction. Note that the study with the biggest and most robust evidence of compensation (on the far right) is a triangle. Perhaps, Pontzer suggests, calorie-saving mechanisms are more likely to kick in when you can’t simply eat more to replace the energy you’re burning through physical activity.

This matches results from animal studies, which tend to see more compensation when diet is limited. And it might explain why groups like the Hadza seem to have such strong compensation: it takes a lot of effort (and a lot of calories) to acquire more food as a hunter-gatherer, so it’s not easy to simply decide to eat more after a physically active day. Their high level of energy compensation may be triggered in part by the relative scarcity of easily available food calories.

Cardio vs. Weights

Another detail in that graph: the filled shapes involve aerobic exercise routines, while the open shapes involve strength training. There seems to be less compensation (i.e. fewer “disappearing” calories) in the strength training studies. In fact, all three of the strength studies shown are above the dashed line, suggesting that total energy expenditure increased by more than you’d expect based on how much they’re exercising.

There are a few possible explanations for this. One is that it’s difficult to measure the exact number of calories burned while lifting weights: the technique used in the studies is better suited to sustained aerobic exercise, so the numbers may be off. On the other hand, it’s possible that maximal strength efforts don’t trigger the same compensation responses as sustained aerobic exercise, or that the metabolic costs of repairing post-workout muscle damage are higher after strength training. But the most important thing to note is that it’s just three data points, so consider this observation tentative for now.

So Does Exercise Impact Weight Loss or Not?

The way I read the data is that there’s probably some compensation that occurs, but under normal conditions without dietary restriction, it only claws back a fraction of the calories you burn. Exercising more burns more calories. What this means about the value of exercise for weight loss depends on whether you’re talking about public health or physiology.

From a public health perspective, the Hadza results and others like them suggest that the reason for the obesity epidemic isn’t simply that we don’t move as much as we used to. The existence of compensation may also help explain why telling people to exercise doesn’t make weight magically melt off. If you restrict diet, then compensation ramps up, making it harder to burn calories. If you don’t restrict diet, then another form of compensation comes into play: you get hungry and eat more.

Still, when people tell me that you can’t outrun a bad diet, my stock response is: How far were you planning to run? In Kristen Howard’s study, the subjects were averaging 32 miles per week, and there looked to be a difference of over 1,000 calories per day in how much the least active and most active subjects were burning. Lots of people run (or bike or swim or pogo-stick) the equivalent of much more than that. A typical resting metabolism is somewhere around 1,600 calories. If you’re burning more than 1,600 calories a day (as the subjects in this study were, for example), it becomes mathematically impossible to “compensate” for all your exercise calories.

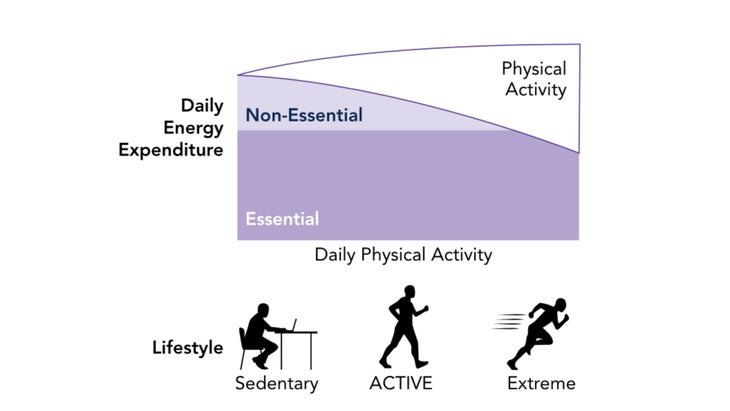

For weight loss in the real world, the question of whether training like a collegiate cross-country runner really works is more hypothetical than practical—or to put it another way, it’s relevant for physiology but not public health. Energy compensation has other potential implications, though. Back in 2018, Pontzer wrote a paper in which he outlined how the body might save calories by cutting back on immunity, reproduction, and stress response. These cutbacks might be beneficial when you go from sedentary to active: a dialed-back immune system, for example, might reduce the negative effects of systemic inflammation. But if you keep pushing far enough, energy compensation could begin to cut into essential functions.

Here’s how Pontzer visualized it in that 2018 paper:

This theory is harder to test, but the idea that too much exercise starts to impinge on important bodily functions fits intuitively with the idea of overtraining syndrome, another concept that remains poorly understood and perennially debated. I’m not sure how to parse the difference between energy compensation from too much exercise and the problems that arise more generally from a caloric deficit (i.e. the interaction of exercise output and caloric intake, rather than exercise alone). The fact that dietary restriction seems to make energy compensation stronger suggests that caloric deficit is a key signal.

I’m afraid this is one of those articles that ends without a definitive answer. The data is sparse and scattered enough to fit with strong, weak, or non-existent energy compensation. That should change, though. Doubly labeled water used to be prohibitively expensive; now it’s on the consumer market through a company called Calorify (for which Pontzer serves as scientific advisor). It’s still not cheap, at roughly $1,000 per consumer test, but we should start seeing more and better research data that directly tests what happens to your metabolism when you ramp up your workout routine. Watch this space.

For more Sweat Science, sign up for the email newsletter and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.

The post Does Exercise Actually Burn Calories? appeared first on Outside Online.