“Big moves on Day 1,” White House senior policy strategist May Mailman crowed on X the morning of President Donald Trump’s inauguration, linking to a news article about a forthcoming executive order. Even amid the barrage of actions during the first hours of the Trump 2.0 presidency, the order—“Defending Women From Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government”—was a bombshell. It directed federal agencies to eradicate every trace of what it called “gender ideology” and established new government-wide definitions of the sexes. “Woman” meant adult human female. “Female” was “a person belonging, at conception, to the sex that produces the large reproductive cell.” Men made “the small reproductive cell.” “Sex,” it decreed, was an “immutable biological reality.”

For at least two years, Trump had been promising to “get transgender out” of schools, women’s sports, and the military. “It will be the official policy of the United States government that there are only two genders: male and female,” he would tell his cheering crowds.

Riley Gaines, the swimmer–turned–anti-trans activist, fangirled, “May Mailman is my Taylor Swift.”

But the order’s sweep and audacity seemed to surprise even Trump’s admirers. “It’s perfection,” Megyn Kelly gushed on her SiriusXM show. “In my wildest dreams, I couldn’t have drafted something this beautiful.” On X, the kudos flowed in from people in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Brazil. Many of the posts singled out Mailman, a Harvard-educated lawyer quickly identified as the order’s chief author. Riley Gaines, the swimmer–turned–anti-trans activist, fangirled, “May Mailman is my Taylor Swift.”

Mailman had spent four years working in the first Trump administration, becoming an immigration hawk and close ally and friend of senior adviser Stephen Miller. During the Biden era, she landed at the Independent Women’s Forum, a Washington power player that rose to prominence by pink-washing conservative economic policies—claiming to champion women’s freedom and equality while actually working to undermine them. There, she threw herself into the anti-trans cause, going from state to state to promote model legislation, known as the Women’s Bill of Rights, that enshrined narrow definitions of “male” and “female” into law.

Now, at the start of Trump’s second term, Mailman was stepping into the spotlight as a White House surrogate and speaking to conservative outlets about the need to “protect” cisgender women. “If men can just assert that they are women and take women’s privacy away, take their opportunity away, take their safety away,” she told a St. Louis radio host, “then there is no such thing as women’s rights anymore.”

But there were intimations that the crusade against trans people encompassed something broader. Mailman wasn’t just anti-trans; she was profoundly dismissive of feminism. “There’s something about, you know, swiping right and left in your apartment by yourself at 11 p.m. after working a hard day that, like, doesn’t feel like feminism is the answer to all your problems,” she mocked on one podcast. She was worried about how “gender ideology” would affect men, too. “Who’s going to be our firefighters? Who are going to be our policemen?” she fretted on another.

At a Federalist Society webinar last March, she urged listeners not to even use the word “transgender,” so as not to give “credence” to the idea of “this being a category of people.” She also raised an essential question: After defining sex in the law and kicking trans women out of sports and sororities, what comes next?

The answer, she suggested, had something to do with sorting out social roles for men and women. “Trying to figure out how much do we care about gender roles, how much should gender roles infect the idea of womanhood, will, I think, ultimately affect our thinking about gender roles absent transgenderism,” she mused.

Then she stopped, as if realizing she was treading into dangerous territory, and smiled. “That conversation is maybe for another day.”

This is the story of an extraordinary effort by the second Trump administration to shape our ideas about who and what men and women are—a campaign that began with the targeting of trans people but has vast implications for the rights of cisgender people as well. At the center is Mailman, who describes herself as “one of the most effective and connected veterans of the Trump West Wing,” the get-it-done woman for Trump’s get-it-done man. “Stephen [Miller]’s the ideas guy,” she told Blaze News in April. “And then I’m trying to be the one who makes it happen.”

In her whirlwind tour through the White House last year, Mailman made quite a few things happen very quickly—including a high-profile pressure campaign against her alma mater Harvard University to adopt Trumpian priorities in hiring and admissions or lose federal funding. Then, after six months, she left the administration, returning to IWF—now rebranded as just Independent Women—to direct its law center. There, she co-authored amicus briefs in two of the biggest Supreme Court cases of the year, both involving transgender students trying to overturn laws that forbid them from playing girls’ sports. The day after oral arguments, Mailman was on Fox News complaining that some of the justices had dared to call the students “transgender girls.”

“The executive order absolutely has implications for heterosexual, cisgender women. Sometimes, I think that’s their main target.”

Her Defending Women executive order—and the other anti-trans federal decrees that followed—had an immediate, sweeping impact on the estimated 2.8 million trans Americans over age 13. On the phone several days after January’s Supreme Court hearing, Mailman tells me the push to enshrine definitions of sex had two goals: to prevent courts and administrators from interpreting existing laws in ways that are inclusive of trans people and to make voters feel alienated from Democrats. She frames the idea that transgender women are women as an “elite” concept. “If the left can’t agree that ‘woman’ means ‘female,’” she says, “there is something very othering about that to most Americans.”

Now feminist scholars are also starting to raise alarms about the order’s implications for non-trans women. They warn it could be used to undo 50 years of legal and economic progress in the workplace, health care, education, and much more. “At the moment, the most painful, prejudicial consequences are for trans people,” says Kathryn Abrams, a University of California, Berkeley law professor studying sex discrimination. But “the executive order absolutely has implications for heterosexual, cisgender women,” she says. “Sometimes, I think that’s their main target.”

For decades, much of the conservative movement has been fighting to undermine anti-discrimination protections based on sex, explains legal historian Mary Ziegler of the University of California, Davis. These include landmark laws like Title IX, which applies in education, and court decisions like United States v. Virginia, which said the government must have a strong reason, based on more than just stereotypes about physical capabilities, to treat men and women differently. Those protections profoundly reshaped American society, giving women more freedom to pursue the lives of their choosing. But they imposed new requirements on powerful institutions that balked at being regulated, and, Ziegler says, they outraged Christian conservatives who believe that “God has a plan for marriage and sexuality and the family” and “God’s plan should be written into the law.”

The right slowed the momentum for women’s equality when it killed the Equal Rights Amendment in the early 1980s and turned abortion into a wedge issue. Decades later, the anti-trans movement’s emphasis on strictly defining sex as “biological” has given conservatives a new weapon to claw back the feminist movement’s earlier gains, Ziegler says. The term “biological sex,” she says, has become “the new takedown strategy for anti-discrimination law.”

Mailman, not surprisingly, disputes that the sex definitions are part of a wider effort to weaken sex discrimination law. “Simply cementing the case that sex is real doesn’t change anything,” she tells me. “It is the status quo.” Nor does she think enshrining sex definitions based on eggs and sperm will lead to women being treated differently from men in, say, classrooms and workplaces. “There’s nothing about that that forces a woman into a separate calculus class.”

But Mailman’s allies in the conservative movement—groups like the Alliance Defending Freedom, the religious right legal organization that has led many of the biggest attacks on abortion and LGBTQ rights—have their own agendas. “What they’re trying to do is to replace sex discrimination law with a Trojan horse sex discrimination law that no longer prohibits sex discrimination,” Ziegler says. Rather than attacking protections head on, she explains, “they’re going to say, ‘American anti-discrimination law means you can treat men and women differently because they have different bodies.’” If courts embrace this logic, Ziegler says, it would be much harder to fight back against potential restrictions on women’s lives—laws that limit job options for pregnant workers, for example, or that ban women from military schools—by arguing they violate the Constitution’s equal protection clause.

“The administration is telling us what their long game is, which is to treat women’s bodies as commodities and to create laws to exert control over these commodities.”

Other Trump 2.0 priorities, like its fixation with increasing birth rates, add to this growing sense of feminist dread. “They’re so open about the fact that they want women to leave the workforce and have babies—the earlier, the better—and fulfill the role of motherhood,” says Ting Ting Cheng, director of the Equal Rights Amendment Project at the NYU School of Law. “The administration is telling us what their long game is, which is to treat women’s bodies as commodities and to create laws to exert control over these commodities.”

“The foundational piece,” Cheng adds, “is defining people by their biology—to essentially see women as people who have one manifest destiny to fulfill.”

Last spring, to mark Trump’s 100th day in office, Mailman spoke with Debbie Kraulidis, vice president of Moms for America and host of its podcast. Inevitably, the conversation turned to trans kids in schools. Mailman recalled her own childhood in the 1990s and early 2000s: “When I was growing up,” she declared, “it was okay to be a feminine guy. It was okay to be a masculine girl.” Nowadays, she lamented, “you can’t be a tomboy anymore, because you’ll get your body parts chopped off.”

The first child of a surgeon and his Korean-born wife, Mailman (née Davis) remembers her upbringing in “middle-of-nowhere” Kansas with great fondness: “For kids who are from small towns,” she told another podcaster, “you really get to build up your self-esteem and try a lot of things.” At Clay Center Community High School (class of 2006), she was a student council officer, drill team member, and athlete (lettering in cheerleading, tennis, and track), as well as the star at the top of the “Singing Christmas Tree.” By college, she was also a committed conservative, serving as treasurer for the University of Kansas College Republicans and interning for US Sen. Sam Brownback, a GOP stalwart who later became governor. But she didn’t seem to take herself too seriously, entering Spike TV’s “sexiest co-ed” competition in 2007 and earning a write-up in the college paper. “If somebody was doing it who wasn’t me, I’d probably be judgmental,” she told the reporter. Then again, “Why not, for $5,000?”

Graduating into the Great Recession with a journalism degree, she joined Teach for America, landing at Pathway Academy, a majority-Black charter school in Kansas City, Missouri. The school’s executive director, Jennifer Fleming, recalls her as “extremely intelligent, very self-motivated, goal-oriented,” building relationships with students and their families. Mailman would later describe implementing strict discipline, like “standing silent lunch,” in her classroom. Her sixth-grade class scored so high on state tests that the school got its accreditation back, Fleming says. The experience seemed to reinforce Mailman’s conservative beliefs. “I had always thought that Teach for America would help me equip people to be responsible for themselves,” Mailman later recalled for a profile on IWF’s website. “But my kids didn’t have the home environment necessary to do school…I became much more focused on what we can do to build families.”

After two years and a master’s degree in education, Mailman headed to Harvard Law, where she chafed at automatically being made a member of the Women’s Law Association, she told me in an email after we spoke in January. “They gave us ladies a little pep speech, saying that women should support each other in class by applauding other women’s contributions,” she wrote. Men had no equivalent. “I hated this. It felt so infantilizing.”

Mailman wanted me to know that as a conservative, she’s in favor of treating women equally; it’s left wingers who seek, through such “race and sex based identity groups,” to treat women as “weak or ill equipped” in her view. (Equal doesn’t mean identical, however: “At the same time, sex exists,” she wrote, citing differences between men’s and women’s LSAT scores.)

Mailman’s aversion to groups like the Women’s Law Association would echo, years later, in her Trump 2.0 campaign to eliminate diversity and inclusion measures at Harvard and other higher education institutions. The problem with universities, she told the New York Times last fall, is their “culture of victimhood—a glorification of victimhood—that is ultimately bad for Western civilization and bad for the country.”

During her Harvard years, she’d felt very much outside the Obama-era political mainstream. “Conservatism was a lonely place,” especially for women, she told a podcaster last year. But that isolation was also empowering: “You end up being very comfortable with yourself, comfortable with your arguments, comfortable not having a lot of friends.” She became president of the ultra-elite Harvard chapter of the ultra-connected Federalist Society. Post-Harvard, she landed a prestigious clerkship with a federal appellate judge in Denver, then moved on to a private law firm. When a Harvard friend reached out with an offer to work at the “center of the universe”—the first Trump White House—she accepted immediately.

Mailman started on day one of Trump 1.0 and stayed until the bitter end. According to emails reported by the New York Times, as deputy White House policy coordinator in 2018, she floated a proposal to send detained migrants to sanctuary cities. She describes herself as part of the “cleanup crew” for the administration’s family separation policy at the border. Later, she was promoted to the powerful White House counsel’s office, where her portfolio included social issues and the administration’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Trans issues were also on the White House’s radar, including a military ban. In 2018, the Department of Health and Human Services even considered an order that would have narrowly defined sex as “immutable biological traits identifiable by or before birth.” But the conservative base reacted with crickets to proposed anti-trans policies, Mailman recounted on a podcast. “Nobody seemed to care, except for people who didn’t like it.”

Indeed, public support for trans rights was at an all-time high. When North Carolina passed a law in 2016 restricting trans students’ bathroom access in schools, Fortune 500 companies boycotted the state. Then in June 2020, the Supreme Court stunned conservatives by ruling 6–3 that firing someone for being gay or transgender violated the federal law banning sex discrimination in the workplace. “It is impossible to discriminate against a person for being homosexual or transgender without discriminating against that individual based on sex,” Justice Neil Gorsuch, Trump’s first appointee to the high court, reasoned in Bostock v. Clayton County. Mailman hated the decision: “I would argue there’s no logic to Bostock,” she told me.

Mailman was still working for Trump when his supporters stormed the Capitol on January 6, 2021. That very day, she accepted a job offer from the Ohio attorney general, anticipating that her colleagues were about to become “unhirable for a very long time,” she later admitted. One month after Trump left office, Mailman also began a fellowship with the Independent Women’s Forum. Like many conservative organizations, IWF was starting to invest in anti-trans politics—putting Mailman at the center of the next big culture war.

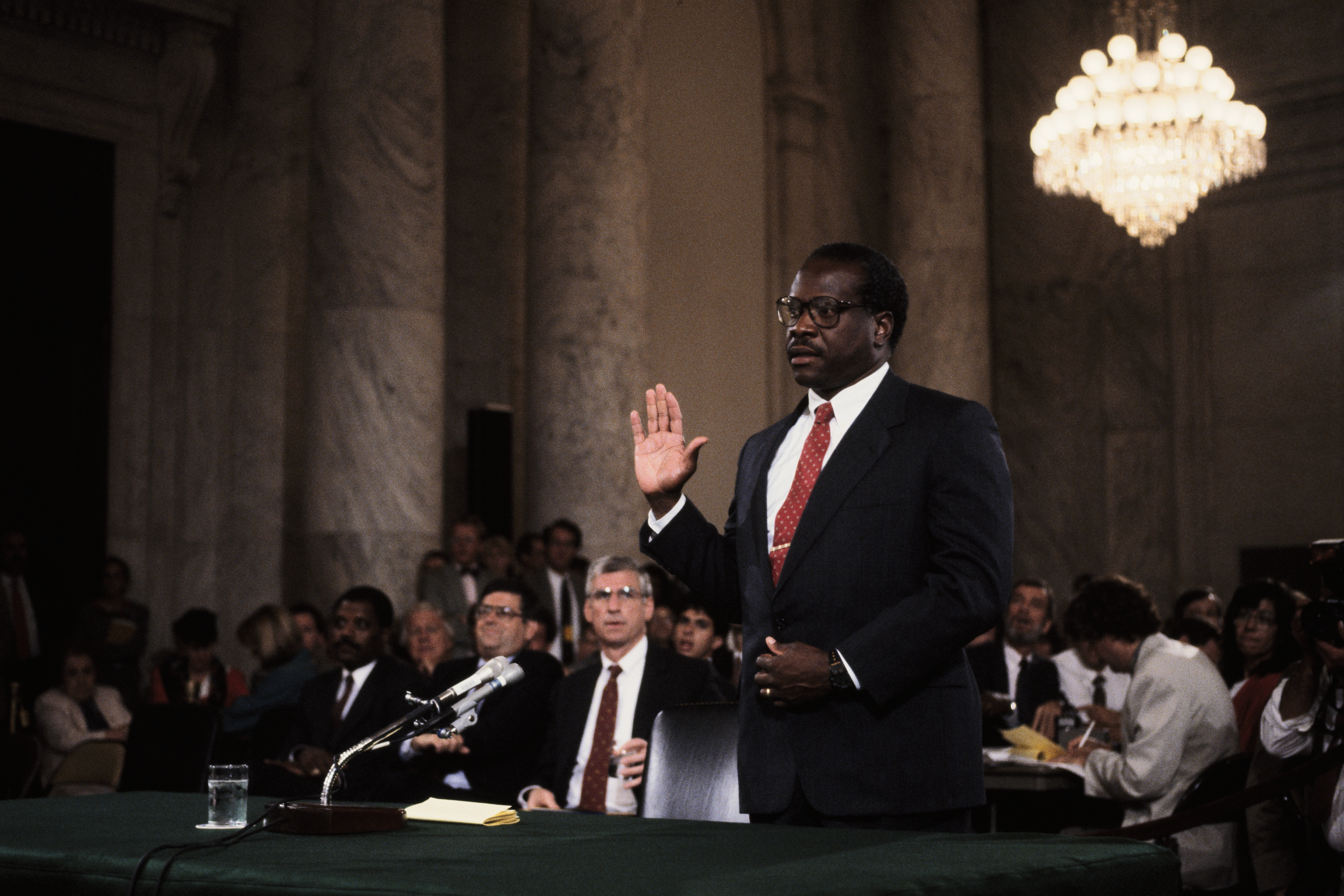

The organization Mailman joined had its roots in the 1991 Supreme Court nomination that was itself a turning point for the role of women in American politics. President George H.W. Bush’s nomination of Clarence Thomas to replace civil rights icon Thurgood Marshall on the nation’s highest court was greeted with howls of liberal outrage. Even before Anita Hill’s sexual harassment allegations threatened to tank his nomination, Thomas’ close friend Rosalie Silberman organized “Women for Judge Thomas” to vouch for his character. Thomas’ confirmation activated a generation of left-leaning women around the issue of sexual harassment. Silberman and her comrades created the Independent Women’s Forum to counter them. “We listened to the spin of those days—the litany that women are victims and men just don’t get it—and decided that those woebegone women did not speak for us,” Silberman said in 1998. “Nor did we think that they spoke for the vast majority of American women.”

IWF’s policy agenda was defined by being anti-regulation and anti–“female victimhood.” At various points over its 35-year history, the organization has opposed the Violence Against Women Act, women’s admission to the Virginia Military Institute, the Affordable Care Act, and paid family and sick leave. It claimed Title IX was being used to defund men’s sports, that sexual violence rates were overblown, and that the gender pay gap was the result of women’s choices. For a time, it was run in tandem with the Koch brothers–affiliated interest group Americans for Prosperity.

From the beginning, much of IWF’s influence was derived from its messaging, starting with its claim to be “independent”—seeming to stand apart not just from feminists, but from ultra-right groups, in part because it didn’t take a public stance on abortion. “Being branded as neutral, but actually having people who know-know that you’re actually conservative, puts us in a unique position,” IWF Board Chair Heather Higgins, a pharmaceutical heiress, explained at an event for potential 2016 donors. “Our value…is taking a conservative message and packaging it in a way that will be acceptable.”

IWF’s first public, tentative forays into anti-trans politics seem to have started around 2017, with news releases ridiculing colleges for putting free tampons in men’s restrooms and for recommending that professors ask students their pronouns. Then in 2019, the conservative anti-trans movement suddenly got serious. That’s when the far-right American Principles Project turned a Kentucky gubernatorial election into a petri dish for anti-trans messaging—and found that a video about a boy in girls’ wrestling struck a nerve.

It didn’t matter that trans athletes were—and continue to be—vanishingly rare, or that lawmakers in some states were unable to identify a single player who would be affected by their bans.

The Democrat won anyway. But conservatives had identified a compelling narrative: Trans people were victimizing female athletes. Within months, Republicans in 17 states introduced a new type of bill, banning trans girls from playing on girls’ sports teams. It didn’t matter that trans athletes were—and continue to be—vanishingly rare, or that lawmakers in states like Tennessee and South Carolina were unable to identify a single player who would be affected by their bans.

The sports issue became the turning point for an anti-trans coalition that included juggernauts of the religious right like the Heritage Foundation and Alliance Defending Freedom. IWF stepped up to provide a female face and voice for the message. Never mind that the “women are victims” narrative contradicted so much of its past work. By 2022, threat of trans athletes had become a central theme of IWF’s messaging. It snapped up aggrieved athletes like college swimmer Riley Gaines, training her to communicate her story of tying for fifth place with transgender swimmer Lia Thomas and eventually hiring her as a spokeswoman. Payton McNabb, a high school volleyball player injured from a spike by a transgender girl, became another “ambassador.”

Mailman embraced the message too, testifying on behalf of IWF against trans athletes in front of a House Judiciary subcommittee. IWF’s media training was a big part of why she joined the group. “I wanted to be on liberal media as a conservative person,” she says, “trying to talk to people,” the way pundits of old used television to shape public opinion when she was a kid.

As Mailman sees it, female messengers have been critical to shifting the narrative around trans issues because—stereotype alert!—they are better at conveying empathy than men. For a long time, she tells me, progressive messages of acceptance and affirmation held sway, and “women do want to be kind, and we do want to be empathetic.” So conservatives needed women to challenge “the empathy play,” she went on. For men, it’s “not their natural language.”

Differentiating the sexes based on such stereotypes is exactly the type of thing that causes left-leaning women to shudder. But one of the most confounding aspects of the Defending Women executive order is its connection to a group of activists who define themselves as radical feminists.

In 2022, IWF announced an ambitious new project that would serve as a prototype for the Defending Women order: a model bill, then known as the Women’s Bill of Rights, that defined male and female in law according to a narrow view of biology. At a press conference, IWF and other social conservatives spoke alongside current and former members of Women’s Liberation Front, a small left-wing group vehemently opposed to the very idea of transgender identity. IWF leaders described their legislation as merely ensuring that policymakers were all on the same page about the meanings of “female” and “male.” But former WoLF board member Kara Dansky, speaking on the call, made it clear that the bill’s goal was to end legal recognition of transgender people. “Everyone is either female or male,” she declared on the call. “Everything else is a lie.”

Sometimes known as trans-exclusionary radical feminists, or TERFs, activists like Dansky believe that women’s rights will be lost if the category of “women” includes people assigned male at birth. They’ve pushed for decades to exclude trans women from women’s spaces. (Some who adhere to these views—including, famously, Harry Potter author JK Rowling—consider the TERF acronym a slur and describe themselves as “gender critical”; others embrace it.) Mailman tells me that TERF activists, particularly Dansky, were the intellectual force behind the effort to enshrine sex definitions. “The ones that were really driving the charge and had just a lot more knowledge and background, and had been thinking about these issues, writing about these issues, for such a long time, tended to be people on the left,” she says. (Dansky, in an email, says she did not contribute directly to the model bill’s language or strategy, though she does call Mailman an “extremely intelligent lawyer.” Like Mailman, she doesn’t believe that enshrining sex definitions could turn back the clock on women’s equality under the Constitution. “Radical feminists are gender abolitionists who fully support women who do not conform to sex stereotypes,” she writes.)

The Women’s Bill of Rights wasn’t the first time radical feminists had teamed up with social conservatives on transgender issues. In 2016, WoLF received a $15,000 grant from the Alliance Defending Freedom to fund a lawsuit over trans students’ access to bathrooms and locker rooms. In 2021, WoLF took another $50,000 from ADF to sue California over a law that allows transgender women to be housed in women’s prisons. “It would be foolish to let performative virtue-signaling prevent us from using available resources,” WoLF legal director Lauren Bone emailed when I asked about the group’s work with the far right.

Both sides have benefited from the strange alliance, Joanna Wuest, an assistant professor at Stony Brook University, points out. Right-wing money and connections allow fringe TERF groups to “punch above their weight,” she says. And conservative Christian groups get “a lot of rhetorical leverage out of saying [that even] radical feminist organizations are opposed to this interpretation of sex as gender identity.”

Conservative Christian groups get “a lot of rhetorical leverage out of saying [that even] radical feminist organizations are opposed to this interpretation of sex as gender identity.”

Soon after the Women’s Bill of Rights was unveiled, Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith (R-Miss.) introduced a version of it in Congress. With the midterms approaching, IWF targeted hundreds of thousands of Facebook users in swing states with ads touting the model bill as part of its supposed crusade for women’s empowerment, boosted by a $100,000 “Innovation Prize” from Heritage. In 2023, versions of the legislation began popping up in statehouses around the country. To promote it, IWF sent Riley Gaines and Mailman—a trip Mailman would later describe as her “first foray into TERFdom.”

Mailman, by then married to former professional baseball player David Mailman, leaned on her own experiences as a woman to advocate for the bills. “‘Identification’ replaced the biological reality that we have been living our entire lives—that I am particularly 32 weeks into living right now,” she said on a stage in West Virginia, visibly pregnant with her second child. Her blitz through the state “was terrifying to watch,” says Khadijah Silver, director of gender justice and health equity at Lawyers for Good Government. “She did an incredible job of flooding legal and political environments, partnering with the right groups, to normalize a regressive and anti-scientific and extremely unfeminist analysis of gender—and make it pretty hard to break through that messaging.”

The Kansas legislature became the first state to pass the bill in the spring of 2023, and when Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly vetoed it, the Republican supermajority overrode her. (“Victory!” WoLF declared in a press release.) Today, 16 states have similar laws, and two more have issued executive orders likewise defining sex.

Logan Casey of the Movement Advancement Project describes the Women’s Bill of Rights as “more existential” than other anti-trans bills. “They’re not targeting just one policy area,” he says. “They’re zooming up and saying across the entire government, here’s how we define the word ‘sex’ so that we can basically apply it everywhere that we want, until somebody stops us.”

Mailman drew on the state sex-definition bills as she drafted the Defending Women executive order. But the ink on Trump’s signature was barely dry before scientists began to push back, arguing that for all the order’s claim to “biological truth,” a modern understanding of sex involves far more than eggs and sperm. Today, many biologists view sex as measured by multiple indicators—hormones, chromosomes, genitalia, brain physiology—that typically but don’t always align.

Scientists began to push back, arguing that for all the order’s claim to “biological truth,” a modern understanding of sex involves far more than eggs and sperm.

More outcry came from reproductive-rights advocates, because the order defined sex as existing “at conception”—language that nods to anti-abortion religious activists who argue that fetal rights begin at fertilization. House Speaker Mike Johnson, for one, was elated about that phrasing, vaunting it during the 2025 March for Life in Washington. Mailman tells me the “at conception” language was added not for abortion policy purposes, but to make the point that sex is determined by DNA prior to birth. Still, “there’s a nice flavor to respecting fetal personhood,” she says. “That’s an added benefit.”

So far, the Trump administration has not used the Defending Women order to pursue anti-abortion policies. Instead, it has zeroed in on attacks on the transgender community. The order had an immediate impact on passports, federal funding for gender-related health research, and transgender prisoners. Soon came more executive orders targeting teachers who supported trans students, schools that let them play girls’ sports, and doctors who provided them gender-affirming health care. Another order stated that being trans “conflicts” with a soldier’s “honorable, truthful, and disciplined lifestyle.” The Departments of Justice and Education formed a special team to investigate schools for promoting “gender ideology”—and some universities, in this new climate, fired instructors and censored Plato.

The changes have been so drastic that federal judges have put many of the federal government’s anti-trans policies on temporary hold. But the ultimate decider will be the Supreme Court, which already has signaled its willingness to interpret sex discrimination law in ways that exclude trans people. Last June, conservative justices ruled 6–3 that states can ban puberty blockers and hormone therapy for transgender minors. In November, the Supreme Court allowed the State Department to stop changing trans people’s gender markers on their passports.

The court is currently considering a pair of cases that directly ask how much different treatment for the sexes based on “biology” is allowable. The cases involve two states, Idaho and West Virginia, which have both passed laws banning trans girls and women from playing on women’s school sports teams.

During oral arguments in January, ultra-conservative Justice Samuel Alito seemed to view the cases as an opportunity to enshrine a constitutional definition of sex: How can a court determine whether there’s discrimination on the basis of sex, he asked, “without knowing what sex means?” But Justice Amy Coney Barrett appeared to understand that there would be greater consequences to a decision that gave states more leeway to treat men and women differently, so long as the state claimed the reason was biological.

“Your whole position in this case depends on there being inherent differences, right?” Barrett asked the lawyer for West Virginia. But, she hypothesized, what if a state could produce studies showing that women’s presence in calculus classes held back men’s learning? Could women be excluded from calculus? “Seems to me like there would be some risk on your understanding that that would be okay,” she said.

The exchange showed that even the Supreme Court justices are thinking about how an anti-trans ruling could have wider consequences for sex equality, says Kate Shaw, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania and co-host of the Strict Scrutiny podcast. “They’re opening up the possibility of much broader potential exclusions,” she says. Such a decision could call into question decades of progress fighting sex discrimination. After all, differences between men’s and women’s bodies have been used for much of human history to justify treating women as inferior to men.

The Trump administration has been open about its desire to return to those old days—from Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s opposition to women in combat to the White House’s reported consideration of proposals for “baby bonuses” to incentivize women to have more children. Even the title of the Defending Women executive order reflects early-1900s logic that the government needs to protect women due to their inherent fragility—an idea the Supreme Court rejected during the sex equality revolution of the 1970s, Shaw argues in a recent law journal article. And at a December press conference announcing a rule targeting trans teenagers’ medical care, Deputy Health Secretary Jim O’Neill described gender roles as divinely ordained. “Men are men. Men can never become women,” he paraphrased Mailman. “Women are women. Women can never become men.” Then he went a step further: “At the root of the evils we face—such as the blurring of lines between sexes and radical social agendas—is a hatred for nature as God designed it and for life as it was meant to be lived.”

It’s the focus on transgender people that gives the administration “cover” to pursue this broader regressive agenda, Ziegler argues. For that strategy, she credits Mailman and her allies. The Defending Women order “is about to matter in a big way,” she says. “It created political cover for all of these changes that are going to affect trans people, queer people, along with cis, straight men and women.”

Mailman left the White House in early August, pregnant with her third child. But she’s found it hard to step away entirely. In addition to rejoining Independent Women, she has launched her own consulting firm and is representing Netflix as it attempts to acquire Warner Brothers Discovery (reportedly alongside Kellyanne Conway, a Trump 1.0 loyalist who used to be on IWF’s board). She also continued to work for the administration in its negotiations with Harvard. At the time we spoke, she hadn’t turned in her government laptop.

On her last official day in the White House, the Wall Street Journal published a story titled, “The Conservative Women Who Are ‘Having It All,’” with Mailman prominently featured. She’d been flying on weekends from DC to Texas, where her husband, who owns a tree-transplanting company, took care of their children with a nanny’s help, the Journal reported. “In theory, I would love to be a trad wife,” Mailman confided. She’d intentionally picked a husband who made more money so she “wouldn’t feel trapped” in the workplace, she said. But she didn’t feel guilty about missing time with her kids: “I don’t have a victimhood mentality.”

For all the praise that conservatives heaped on Mailman for her work in the White House, these details about her home life rubbed some the wrong way. A few weeks later, the Institute for Family Studies, a right-wing think tank, started publishing rebuttals to the Journal article—and to the lifestyles of the conservative women it featured. “There is no boss, no industry, no political administration or nation who needs a woman more than her children need her,” one writer, Maria Baer, reprimanded.

Baer was calling out Mailman for defying the gender ideals that social conservatives were working so hard to promote. And then Baer stuck in the knife: It was a matter of biology for women to devote themselves to mothering. “We pursue high-powered careers because we want to make an impact, to leave a legacy, to be remembered, or to change the world,” Baer wrote. “There is no surer way to accomplish each of these than by mothering our own children—a job which, by definition, no one else in human history can do.”

Mailman probably shouldn’t have been surprised. But the criticism from an organization she respects came as a blindside. “It was frustrating,” she tells me on the phone, her baby fussing in the background. “I felt like I was getting critiqued on something that I literally was actually doing the opposite on.” She’d joined the Trump transition team thinking her tenure would be brief, she says, then accepted a job in the administration to “help my friends,” but only for six months. She’d repeatedly said no to working in the White House “because I wanted to be around my young kids and my husband, not for any cultural pressure reason, but that’s what’s best for me and for what I wanted.”

It was yet another reminder that, despite Mailman’s insistence that defining sex narrowly wouldn’t affect women’s equality, right-wing groups can’t be counted on to go along with that rosy thinking. Nor did it seem to strike her as contradictory that being able to pursue “what’s best for me and for what I wanted” depends on the very feminist gains that those groups—now armed with the Defending Women order—are working to undermine.

But Mailman was too busy to be upset at her allies-turned-critics. “Everybody is going to have their own opinion about everybody else,” she says. “You just move on.”