A nasty cold or a bout of flu is a nuisance for you; it’s a complete disaster for the 2,900 athletes currently gathering in Milan, Italy, for the Winter Olympics. Staying healthy is one of the crucial prerequisites to climbing onto the podium. That’s not just hyperbole: a study of Norwegian cross-country skiers found that Olympic and world championship medalists averaged just 14 days per year with colds and minor stomach bugs, while non-medalists averaged 22 days.

As a result, Olympic medical staff spend a lot of time and effort trying to figure out how to keep their teams healthy. If you’re hoping to stay healthy this winter, you could do worse than emulating their approach. There are three main strategies to consider: avoiding exposure, boosting your immune defenses, and fighting infections immediately after they take hold.

Avoiding Exposure

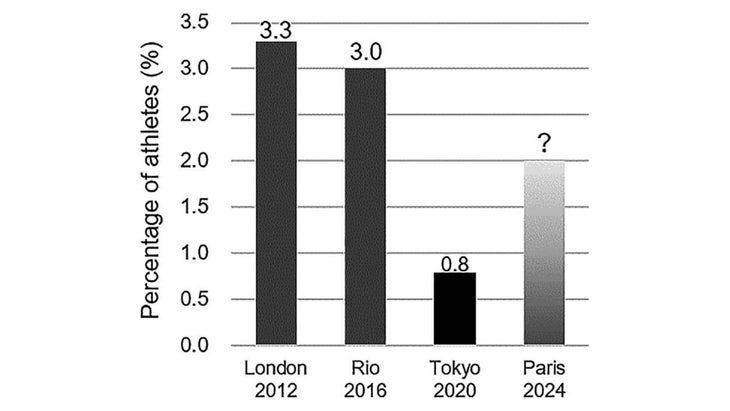

At the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, infection rates among athletes were 73 percent lower than at Rio 2016 and 76 percent lower than at London 2012. It’s not hard to guess why: anti-COVID measures kept other infections from spreading. Heading into the Paris Olympics in 2024, the big question was whether athletes had learned enough from this experience to keep infection rates low.

Here’s a graph that South African sports medicine physicians Marcel Jooste and Martin Schwellnus published in the months leading up to the 2024 Games, posing this question:

There hasn’t yet been comprehensive health data from 2024 published, Jooste told me. But he pointed to some preliminary data on illness rates in the United States team, which suggests that they did indeed jump back up to pre-pandemic levels. The rate for respiratory infections, for example, was a stunning 8.6 times higher in Paris than in Tokyo.

Interestingly, the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee medical staff reporting this data point out that they had a warning this would happen because illness rates were also high at the 2023 Pan Am Games in Santiago. In response, they focused on simple illness prevention measures in the lead up to Paris: masking, hand hygiene, and avoiding crowds, particularly during travel. But adherence was low. Athletes simply couldn’t be bothered, even with potential medals at stake.

There are more complicated ways of reducing exposure. A few months ago, USOPC’s chief medical officer, Jonathan Finnoff, gave a fun interview to the Wall Street Journal where he suggested more esoteric tactics like choosing window seats in the middle of the aircraft, which tend to have the least passing foot traffic, and directing the overhead air nozzle between you and your seatmate to create a germ barrier. At the Vancouver Olympics, Norwegian athletes were issued plastic sheeting to cover germy hotel carpeting. But it’s hard to imagine that any of these tricks are more effective than basics like masking and avoiding crowds.

Boosting Immunity

Even if you’re really good at avoiding exposure, you’ll encounter some germs eventually—and when you do, you’ll hope that your immune system can deal with them. Getting a flu shot is a good start, as is taking care of basics like getting enough sleep. Jooste points out that athletes are two to three times more likely to pick up an infection when they travel across more than five time zones.

But it’s not just sleep: immune function is also suppressed by stress. In athletes, that can take the form of hard training, but more general life stress also plays a role. In a study published last fall by Sophie Harrison of the University of Bangor, for example, runners who reported higher levels of anxiety were more likely to pick up a respiratory infection in the weeks following a marathon. It’s not always easy to dial back stress in our lives, but understanding its potential consequences is a good motivator to take it seriously.

There are also a near-infinite number of supplements that claim to boost immune function. Few have much evidence behind them, but two that Jooste and his colleagues highlight are vitamin D and probiotics. I’ve generally found the evidence in favor of vitamin D as a sports supplement to be unclear, but keeping your levels above the “deficient” threshold does seem like a good idea. For probiotics, they suggest multi-strain combinations of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium at a dose of at least 1 billion CFU per day.

Fighting Infections

If the first two strategies—avoiding exposure and boosting immunity—fail, then your last hope is to fight an infection as soon as it takes hold. At the 2018 Olympics, the Finnish team took an aggressive approach to identifying and immediately fighting infections, and subsequently detailed the results in a journal paper. (My favorite nugget from that study was that they tracked how infections spread on the flights to South Korea, and found that sitting in business class was the best way to stay healthy and avoid passing an infection on to others.)

On a more practical note, any athletes or team staff feeling under the weather immediately took a nasal swab that was fed into a rapid analyzer to determine whether they had the flu or some other type of infection. If they had the flu, they were given Tamiflu, which is most helpful in shortening the illness if started within 48 hours of the first symptoms. A recent article in The Atlantic highlighted another antiviral, Xofluza, which offers similar benefits—getting better roughly a day sooner—from a single dose (rather than ten doses of Tamiflu), comes with fewer side effects, and is apparently more effective at reducing transmission to others. Antivirals remain a relatively niche product, but they’re something to keep in mind if you’re in a high-stakes situation where you really need to get better as soon as possible.

If, instead of the flu, you have a bacterial infection like strep throat, you need antibiotics. For a plain old cold, there are fewer options. Both Jooste and exercise immunologist Neil Walsh note that there’s some evidence for zinc lozenges to shorten the duration of colds if you take at least 75 mg per day starting less than 24 hours after symptom onset, though the evidence remains contested.

None of these strategies will guarantee you a healthy winter. But the dip in Olympic infection rates during COVID and the subsequent rebound should reassure us that we do have at least some control over our fates. Whether masking up and avoiding crowds seems worthwhile is entirely up to you—but if you have an upcoming event or trip where you really don’t want to be sick, you know what to do.

For more Sweat Science, sign up for the email newsletter and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.

The post The 3 Steps This Year’s Olympic Athletes Are Following to Avoid Illness appeared first on Outside Online.