The Grand Canyon is one of the world’s most famous waterways, and its stretch of the Colorado River and its tributaries are protected. But a new study has discovered that some of the canyon’s water systems may contain pharmaceutical drugs and forever chemicals.

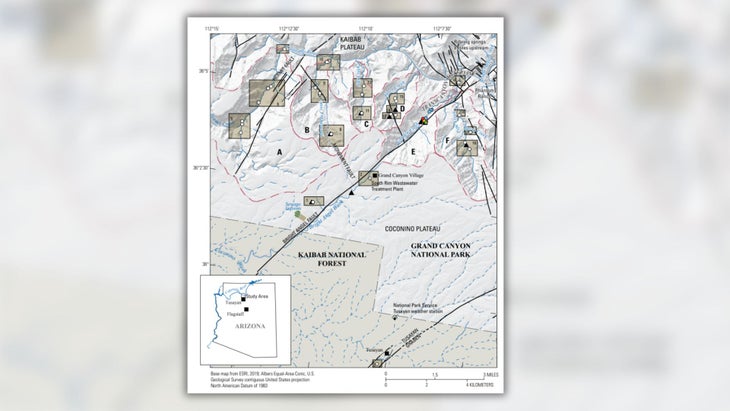

Researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and National Park Service (NPS) found multiple contaminants of concern (CECs) in water emerging from several springs near the Grand Canyon’s South Rim. These areas include the Bright Angel Wash, Monument Spring, and Upper Horn Bedrock Spring.

The USGS published the findings in a scientific investigation report last December.

Monument Spring, which feeds into the Colorado River, showed traces of multiple pharmaceutical medications, including an antibiotic, antifungal, antidepressant, and a diabetic drug. The amounts are small, but experts say the findings indicate wastewater from a nearby treatment plant is somehow seeping back to the canyon and the Colorado River, a major water source for plants, animals, and humans in the region.

Other detected CECs included several per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as forever chemicals, used in a number of products, including waterproof outdoor gear and nonstick cookware. PFAS are linked to health concerns, including cancer and infertility.

Studies show that small amounts of pharmaceutical drugs are present in freshwater sources worldwide. None of the drugs found in the Monument Springs were shown to exceed drinking water standards.

However, the study authors added that “most of the compounds detected have no regulatory standards,” meaning it’s hard to really tell how much is too much.

Mike Fiebig, southwest river protection director for the nonprofit American Rivers, told Outside that, although the CECs were found in small amounts, the findings are concerning for animals that depend on the springs, especially frogs and salamanders. Scientists also believe PFAS can disrupt the body’s hormones, potentially interfering with an animal’s sexual function and reproduction.

“Not only could these cause problems for the reproductive systems of sensitive species, but backcountry recreationists likely don’t want to be exposed to these chemicals either, even though they are at low levels,” said Fiebig. Typical wastewater treatment plants are designed to treat biological contaminants, such as feces, not chemical contaminants.

“Being common doesn’t mean that it’s OK, though. There is growing concern about CECs and pharmaceuticals in wastewater across the country,” Fiebig added.

There are different methods for removing these chemicals from wastewater, but Fiebig said they’re expensive and oftentimes difficult to implement. NPS, which manages the treatment plant where the contaminated water is likely coming from, is already operating with a severely reduced budget due to federal cuts in 2025.

“The NPS might not have the funds or the staff remaining to implement such a fix,” Fiebig said.

The facility involved, the South Rim Wastewater Treatment Plant, was designed to send its treated water away from the gorge. However, Fiebig says the treated wastewater is probably entering groundwater and returning to the springs around the South Rim through the Bright Angel Fault, a geological fault line that cuts through the Grand Canyon.

“Without knowing the geology where the treatment plant sits and drains, there might also be an option to divert the drainage away from the Bright Angel Fault, though this could also be expensive or infeasible depending upon the substrate. It would also end up dumping it elsewhere,” said Fiebig.

Even if the sources of some contaminants, like PFAS, were removed from the water supply at their source, the drugs would likely still be found in the water.

“Pharmaceuticals most often travel to the wastewater treatment plant through urine, which is unavoidable,” said Fiebig. It’s important to remember that similar issues with treated yet still contaminated wastewater are occurring across the nation, including in wilderness areas and water bodies with much less public visibility.

“The springs, seeps, and tributaries of the Grand Canyon are very sensitive desert ecosystems, and we’ve committed to protecting them at a high level,” said Fiebig. “Just because ecosystems aren’t protected to the level of Grand Canyon National Park, that doesn’t mean that we want these chemicals and pharmaceuticals in them either.

The post The Grand Canyon’s Water Is Supposed to be Pristine. Scientists Just Found Pharmaceuticals in It. appeared first on Outside Online.