I have a runner friend who claims he has to avoid doing too many push-ups, otherwise he starts to bulk up so much that it interferes with his running. It’s hard to understate how annoying I find this. I also have trouble believing it, to be honest, as someone who never seems to add any muscle at all no matter how many push-ups I do. Is it really possible that people can have such widely varying responses to the same exercise stimulus?

As it turns out, this is a hot question in exercise physiology these days. The traditional view is that yes, of course there’s individual variation in how people respond to training. That’s part of how we define “talent.” In fact, some scientists even argue that there are some unlucky “non-responders” among us who don’t get fitter at all when they train. But a more recent line of research has pushed back against these notions, using statistical analysis to suggest that the apparent variations in response are just the result of measurement error and day-to-day biological variability. I took a deep dive into this question last year.

Now a new study in the European Journal of Sport Science brings some fresh data to the debate. A research team led by Juha Ahtiainen of the University of Jyväskylä in Finland put 20 subjects through two separate ten-week strength training programs, separated by a ten-week washout period, to see whether the same people tended to be the biggest (or smallest) gainers both times. The results suggest that some people really do pack on muscle (and/or get stronger) more easily than others, but that everyone benefits to some extent.

The Evidence for Individual Variation

The strength training program in the study was fairly standard. Subjects worked out twice a week, doing five exercises targeting the upper (e.g. bench press) and lower (e.g. leg press) body, with three to four sets of eight to ten repetitions, finishing within a rep or two of failure. The outcome measures were muscle size, measured with ultrasound, and muscle strength, measured as one-rep max for leg press and barbell biceps curl. (More muscle and more strength mostly go together, but not perfectly: some strength gains result from improving the signaling between your brain and muscles, for example.)

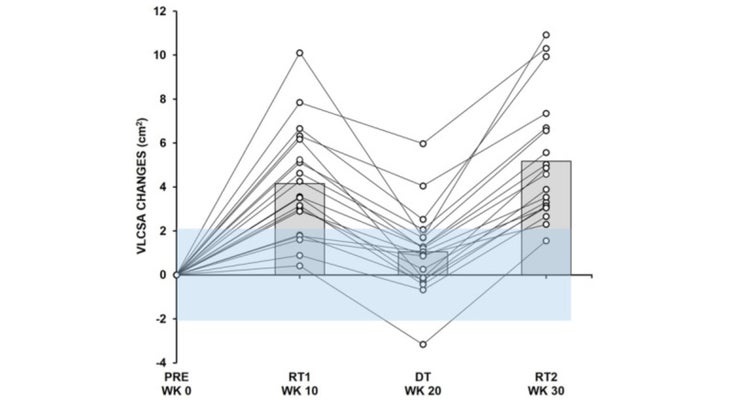

Here’s what the resulting data looks like for leg muscle size. The measurements are taken before training, after ten weeks of training, after ten weeks of no training, and then again after a second ten weeks of training:

In the individual results (the lines and circles), there are some lines that cross, but for the most part the biggest gainers in the first session were also the biggest gainers in the second session.

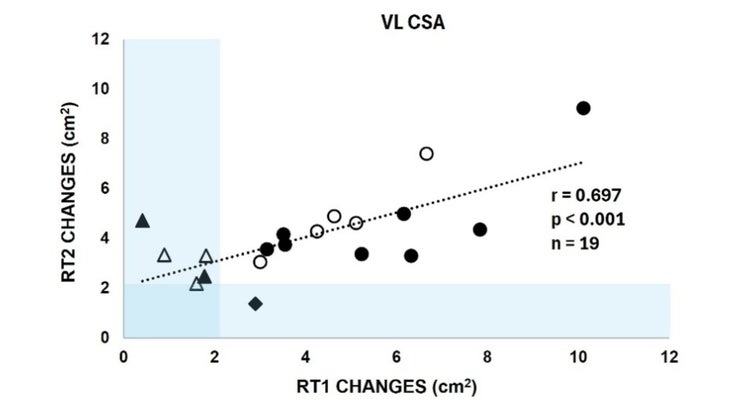

Another way to visualize the same data is to plot the increase in muscle size in the first session on the horizontal axis and the increase in the second session on the vertical axis:

Once again, the big gainers in the first ten weeks (on the right-hand side of the graph) tend to also be the big gainers in the second ten weeks (on the upper part of the graph). The results are very similar for arm muscle and for arm and leg strength. This seems like pretty strong evidence that we don’t all get the same amount of juice from each squeeze of strength training.

The Myth of Non-Responders

There’s another interesting feature in the graph above. The shaded blue areas represent the “minimal detectable change,” based on how much these measurements changed in a control group that didn’t train at all for ten weeks. If you’re in the shaded area, then your improvement was too small to be sure it’s not just measurement error. Notice that nobody is in both shaded areas—that is, there’s no one who didn’t get bigger leg muscles during at least one of the two training periods.

Back in 2012, a BBC journalist named Michael Mosley produced a documentary called The Truth About Exercise, in which he reported on emerging research suggesting that some people are wired not to respond to exercise. He did four weeks of supervised workouts and didn’t get fitter, seemingly confirming this hypothesis. “It turns out that the genetic test they had done on me had suggested I was a non-responder and however much exercise I had done, and of whatever form, my aerobic fitness would not have improved,” he explained.

Not surprisingly, this idea of exercise non-responders became very popular: it’s nice to think that any shortcomings in your fitness can be blamed on your genes. But in the years since then, other researchers have pushed back. Several studies have found that if you take people who don’t respond to a given training program and, well, make them train harder—then lo and behold, they get fitter. Make the training program hard enough, and eventually everyone responds.

The new Finnish study offers a twist. Instead of making people train harder, they just repeat the training program a second time, and this effectively eliminates non-responders. Why do some people not respond the first time but respond the second time (or vice versa)? Maybe they were tired or sick or stressed out during one of the training periods. Maybe they had some water retention that made their muscles seem bigger during the baseline tests. Maybe the researchers read the ultrasound wrong. There are any number of possible reasons, none of which are inherent to their genetics.

The scientific debate about individual variations in response is actually quite complicated, and very important. I don’t want to take a drug based on its average response if my personal response happens to be twice as weak or twice as strong as that average. For exercise, too, understanding our personal responses should, in theory, enable us to get the most out of our training. The new study reassures me that I’m not just imagining that my overly muscled friend gets a bigger bang from his strength workouts than I do—but just as importantly, it also tells me that if I stick with it, I’ll eventually see results.

For more Sweat Science, sign up for the email newsletter and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.

The post Why Some People Put on More Muscle Than Others appeared first on Outside Online.