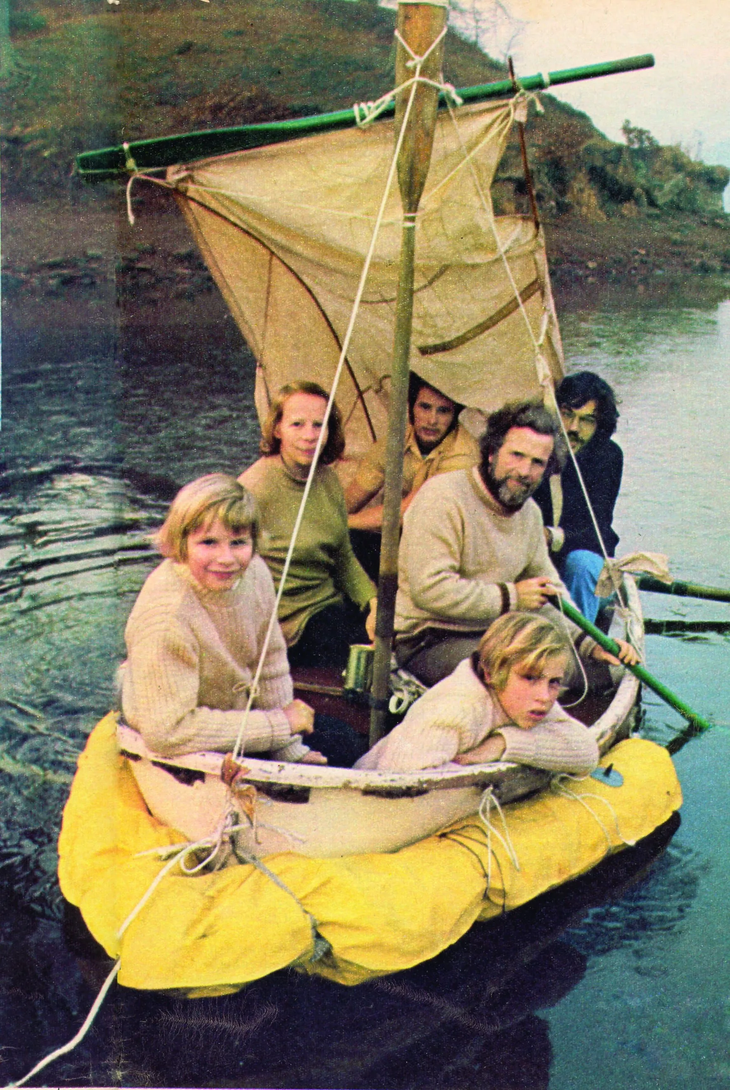

Outside is known for covering survival stories, from the 1996 Everest disaster that inspired Into Thin Air to the original story behind The Perfect Storm. These real-life tales often center on heroic individual feats, or a team, or group of friends, that band together to make it through. What makes Apple’s new podcast Adrift unique is that it tells the extraordinary story of a family who survived against all odds at sea for 38 days after being shipwrecked. A dream voyage of sailing around the world turned into a harrowing disaster when three orca whales hit their 43-foot wooden schooner and sank it within minutes. Stranded in the vast Pacific Ocean, 200 miles west of the Galapagos Islands, the Robertsons had no radio nor compass, and battled heavy storms and sharks circling. All they had left after their sailboat sank was an old inflatable rubber life raft, a nine-foot fiberglass dinghy, a few tins of food, and each other.

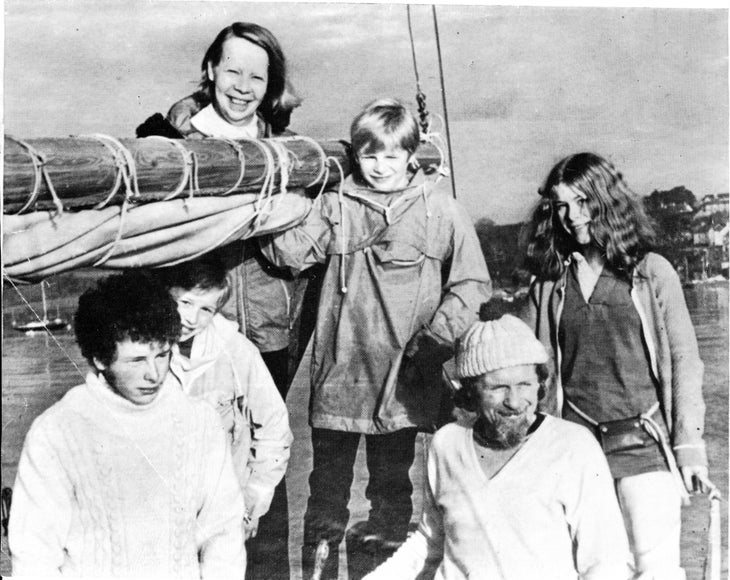

Adrift, an eight-part original podcast produced by Blanchard House, dives into the incredible true story of the Robertsons, a young British couple, Dougal and his wife Lyn, who sold everything they owned and and set out to sail around the world in 1971 with their four children: their daughter Anne, 18, their son Douglas, 16, twin sons Neil and Sandy, 9. They were also joined by a student hitchhiker, Robin, they picked up in Panama. When disaster strikes, their family odyssey turns into a desperate mission to survive.

Now, nearly six decades after they were castaways at sea, the Robertsons’ survival story is being re-told for today’s generations and brought to life with immersive audio, exclusive interviews revealing never-before-heard details, and an emotional reunion for the first time with the Japanese fisherman who rescued the family.

Outside talks to Douglas Robertson, who was a teenager at the time, about his family’s incredible survival story, along with Adrift’s producer Ben Crighton.

Outside: Douglas, tell me what you remember from that fateful day when you and your family were shipwrecked.

Robertson: We’d sold the farm two years earlier; we were dairy farmers. We bought this yacht to start our trip around the world. We sailed through the Panama Canal and Pacific Ocean to the Galapagos Islands. We had set sail from the Galapagos two days earlier and we were 200 miles west of the westernmost point of Galapagos.

Then it happens … Bang, bang, bang … Three killer whales hit us out of the blue. In fact, there’s a painting of this moment—what I saw the moment after we were hit, a big daddy, a tiny baby and a mother, sort of middle-sized one beyond the baby. The daddy had his head split open and blood was pouring out. Now, to me, whales, wild animals, don’t take chances. We can’t ask the whales. But I would submit that he attacked us. He definitely thought we were food for the rest of the pod. When he hit the boat, a three-ton led keel of a very heavily built yacht, he paid for it with his life, probably, and him paying for it with his life gave us time to get away. The whales never tried to attack us in the water, although we were very vulnerable in the water.

We saw [the whales] momentarily, and then they were gone. We were terrified. I absolutely thought, this is it. You’re going to be eaten alive, Douglas, this is how it’s going to end. I kept feeling my legs because I’d heard that you don’t feel the bites. I still had [my legs]. And I stayed in the water long enough to try and fix the raft up.

What was going through your mind at this point after you survived the shipwreck?

Robertson: It wasn’t until the following day that we managed to bail out the dinghy and that we started to make progress, and we realized how fortunate we were to have the the raft in the first place. Just incredible. It was terrifying, obviously, for the consequences seemed so vast.

And then when we were in the raft and the yacht was gone, suddenly sailing round the world was finished. It was over in a flash, and now we’re sitting in a raft wondering how the hell we were going to do anything to survive. We didn’t know what to do. We had no answers, lots of questions, no answers. And we were scared, and we said the Lord’s Prayer. We were frightened and we didn’t know what the future held for us. We watched a flying fish jump out of the sea and a frigate bird swooped down and plucked it out of the air while it was flying along, as if to mock us, saying look what I can do, I can get food, and I’m only a bird.

You humans think you’re so clever, what are you going to do now?

And I looked at my dad, and said, good god, they’ve got millions of years on us, those birds. And he said: Douglas, we have brains, and with brains, we can make tools, and with tools, we can bridge that gap. I doubted whether that was true or not, but it did turn out to be true because we did make tools, and we did catch fish and we caught rainwater, but made some plans about what to do.

Here we were in this predicament, that must be one of the worst predicaments you can be in, especially for my parents sitting there with their kids in front of them. The only probable outcome of this is that we’re all going to die and my mom said to my dad.

She said, Dougal, tell us, are we going to die? We need to know.

In an instant, one family’s boating trip turns from a magical adventure to a desperate fight for survival.

Listen to @AppleTV‘s Adrift, hosted by @beckmilligan.https://t.co/xdg4tX4hnK pic.twitter.com/SgesXNQqug

— Apple Podcasts (@ApplePodcasts) December 19, 2025

And [my father] sort of hummed and hawed for a minute or two and wondered whether he should tell us the truth, or whether he should just make up a story that actually, we’ll get out of this somehow. And he decided he would tell us the truth. So he started to tell us the truth, starting back at the beginning.

We were 200 miles west of Cape Espinosa. We were two degrees south of the equator. We’ve got the southeasterly trade winds behind us. We’ve got the dinghy, we’ve got the raft. We’re all alive. We all made it, including my mother, who’d got caught under the rigging as the Lucette went down.. And as he was saying, the shipping lanes lie 400-500 miles to the north. We could make for the shipping lanes. We had enough food and water for 10 days. Surely somebody will pick us up in 10 days time.

The big difference in our survival story was that the leaders, my dad and my mom, were not trying to survive to save their own lives. They didn’t care, but they sure as hell wanted to save the lives of their children.

A plan came to his mind. He asked me to row back to the Galapagos Islands with the dinghy, because we had the dinghy and the raft. You did not argue with him. You know, he was the master and commander of the family. But for the first time in my life, I stood up to him and said, that’s a fool’s errand.

He then said he was sorry that he should never have asked me, because it was a fool’s errand. During that time, we made promises, pledges to each other, very comforting. Very, very comforting indeed, because we were all a bit scared and very uncertain about the future, and we’d heard stories about survivors eating each other and drinking blood and all that sort of stuff. We made a pledge to each other that we would not eat each other; we would die quietly together as a family.

And we were a family. Even though Robin [the student hitchhiker] was with us, we treated him like my older brother. We decided that we would help each other die, if that’s what it came to. We wouldn’t try to eat each other, which to us, seemed an abomination. My dad said I will not rest until I get you on a steamer home. That’s my promise to my family, that I will try hard every day to get us closer to rescue, closer to land. I will not stop trying.

And finally, we would all try to stay alive, because it’s no good having those two pledges if we didn’t really try to stay alive and make the effort to stay alive. Whether we should find land eventually, or whether we could get picked up by a ship at some point in the future, we didn’t know what the outcome might be. But f we could stay alive, at least we’d be there for that outcome.

So we made these promises to each other, and they were very comforting, indeed, very, very comforting that we had sort of made a bond, if you like, a contract.

We had a common goal in mind, which was to try and save ourselves and so began our voyage, our great, fantastic, ridiculous voyage north into the center of the Pacific Ocean.

And as Ben [Adrift’s producer Ben Crighton] said, the big difference in our survival story was that the leaders, my dad and my mom, were not trying to survive to save their own lives. They didn’t care, but they sure as hell wanted to save the lives of their children.

Douglas, tell me how your time at sea—your family’s incredible survival story—shaped the rest of your life?

Robertson: I know it sounds crazy, but I went into the Merchant Marine. That’s what I wanted to do. And I did. I went back to sea, and in 1975 was sunk again in the Pacific Ocean. Big ships don’t often sink, but this was in a very bad storm, and the ship had a mechanical failure. I was in the Merchant Marine for 10 years. It quelled my ambitions. I got married, and had a family, and I wanted to stay at home with them, and so I retrained as an accountant in my early 30s and became an accountant, and I’ve been an an accountant ever since.

My son had a very bad accident, from which he was brain damaged in 2004. I had to fly to Australia on Christmas Eve to basically spend the last few hours that I could with him, but he survived. I suddenly found myself in a special care unit in Australia, on the other side of the world, counseling parents who had also got their children in there. The hospital asked me if I would speak to these parents because they were distraught. And indeed, my wife was totally distraught by what had happened. [My son] Josh was in a coma for three months and unconscious for another month after that, so this was like a major accident. The expectation of life was very low, but I said to myself, this is how my father felt during our survival story at sea. He’d did not know how he was going to save us, but save as he would.

I thought, I don’t know how I’m going to save Joshua, but somehow I’m going to save him, and he’s back home, and he’s not fixed by any means. He is disabled, but he’s alive and beautiful. [Our survival story] has enabled me to deal with things like that.

Robin said he would never work far away from food again in his life, that the spirit of adventure is still with him. He had bowel cancer, and he’s in remission now. And he said that those days on the Pacific had armored him, taught him how to deal with [it]. He wasn’t going to let it get him down. He was going to use the benefits to take him forward.

Now, all of that came from being successful. We were successful. Had we not been successful? If only one of us had survived, it might have been very different, but, we did survive.

Last year, we went to meet the captain of the ship that rescued us. Wow, we had this fantastic reunion with him. He’s 88 years old, and of course, he still remembers. He took one look at my big belly and said, you must be doing well.

That was the full circle of it.

Crighton: There’s a great line in the podcast, in the final episode, where Douglas says, I felt like I was hugging my dad. I felt that Captain Suzuki for a moment in time was my dad. Wow, it was a highly charged movement.

Robertson: I put my arm around him and hugged him. I only know arigato [thank you in Japanese]. And I’ll tell you, it was a surreal experience, because the last time I’d seen him, he’d pulled us out the ocean in the Pacific Ocean, 52 years ago.

So this story is being re-told in a new medium, a podcast, with an original score and sound design created from sound recordings from around the world. How does this help bring the Robertsons’ story to life?

Crighton: We wanted to bring the listener into the boat itself. The sound and the music are hugely important. We had a dedicated team of composers and sound designers. We spent a few days on a similarly sized boat, collecting all the sounds: below deck, above deck, sounds of sails filling with wind. The ruffling of taking down sales.

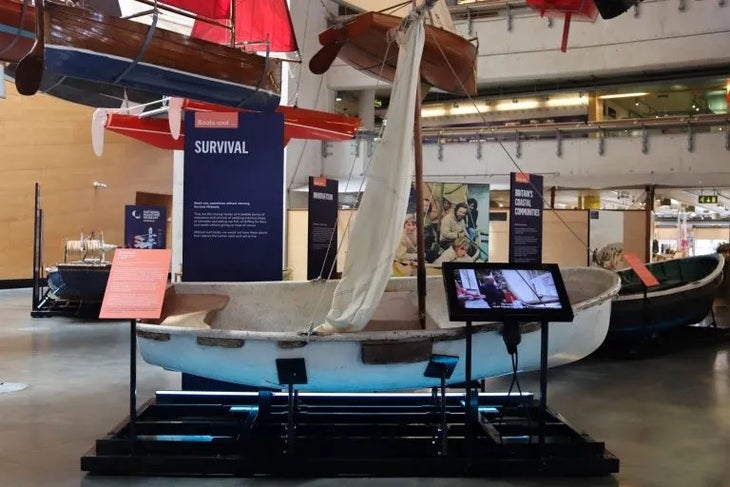

And then we tried to gather a sort of library of sounds of what life would have been like on the loose ends. Obviously, we had these different environments. You have life on board the boat, then you have life aboard the life raft, which is a sort of a fabric environment. And what Douglas hasn’t told you, that life raft was already old and was already starting to fall apart.

Of course, bringing the Robertson story to life through that brilliant and vivid sound and music, but principally through incredibly in-depth character interviews. And our reporter, and host Becky [Mulligan] was so good at, at getting really deep.

What we quickly realized was that when you go through something like this, it’s almost as if it’s sort of imprinted on their memories, and you just have to kind of nudge it, as Becky does, and suddenly you’re right back there in that very moment, sort of present tense. You could see Douglas with almost like a sort of 1000-yard stare. He’s there again. And that’s what was extraordinary about these is that we kind of felt we were right back there in that boat, in that life raft, with them, his family.

Can you transport us back? And the way they responded was as if they were still there. And so the possibilities of making this such a powerful podcast, and the ability to bring the listeners to that moment.

Douglas, what’s your greatest hope of re-telling your survival story? What do you hope today’s new generation of listeners take away?

Robertson: Where there’s life, there’s hope. If you can stay alive, a solution will come your way. And don’t give up, no matter how impossible it looks. You might be quaking on the inside, but just because it looks improbable now does not mean it will remain like that over the days to come. At the end of the day, it’s your life that’s important. Nothing else is important.

If you have your life and you’re still alive, you still have a chance. And that’s what I used to say to those people in the hospital. I was able to say to them: Look, you’re still alive.

This interview was edited for space and clarity.

The post ‘Adrift’ Dives Into the True Story of a Family Lost at Sea for 38 Days appeared first on Outside Online.