“Whoa, headrush!” Over the years, I’ve gotten very familiar with that sensation: a sudden lightheadedness if I get up suddenly after, say, chilling on the sofa. It’s called “orthostatic intolerance,” and it’s a relatively common phenomenon among runners, which I’ve always assumed had something to do with being really fit and having a low resting heart rate. But a new study suggests there’s something entirely different going on.

A team of researchers at Penn State and Florida State universities, led by Chester Ray, tested the hypothesis that the up-and-down motion of running causes the motion sensors in your inner ear to become less sensitive—which in turn means they’re slower to detect when you suddenly stand up. Their study, which appears in the Journal of Applied Physiology, had sedentary volunteers complete eight weeks of either running, cycling, or no exercise. Sure enough, running had a unique impact on their inner motion sensors.

Your inner ear has two main functions: hearing and balance. The balance part, also known as the vestibular system, relies in part on a bunch of rock-like crystals called otoliths, which is Greek for “ear stones.” When your head moves, gravity makes these crystals move around; their motion is detected by small hairs that then signal to your brain which direction and how quickly your head is moving.

This motion-sensing system is important to help you avoid fainting whenever you stand up. As you change your body position, gravity will cause your blood to redistribute itself within your body, tending to pool in your legs when you’re vertical. That can leave insufficient blood—and oxygen—to fuel your brain, which is what makes you feel lightheaded. To prevent that, the body responds by constricting blood vessels and pumping your heart harder and faster. This response is triggered in part (though not exclusively) by signals from the otoliths.

Ray and his colleagues put their volunteers through a fairly rigorous training program that ramped up to two long runs or rides of 60 minutes and two interval sessions each week. The program worked: the runners increased their VO2 max, a measure of aerobic fitness, by an impressive 25 percent, and the cyclists increased by 20 percent. Average resting heart rate dropped from 61 to 53 beats per minute in the runners, and from 65 to 55 in the cyclists. In the control group, by contrast, none of the fitness parameters changed.

To measure the sensitivity of the otoliths, the researchers put their subjects through a procedure called “head-down rotation,” which basically involves lying on your stomach with your head dangling off the end of a table while the scientist moves your head around to shake the otoliths up. Then they used electrodes to measure the nerve signals traveling from the brain to the calf muscles: the idea is that these signals would tell the blood vessels in the calves to constrict if you were about to stand up. Sure enough, the signals decreased dramatically after eight weeks of running, but didn’t change after eight weeks of cycling or not exercising.

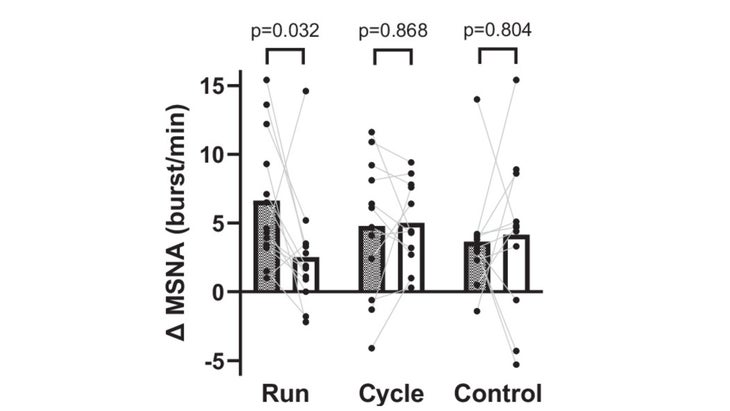

Here’s what that data looked like, where “MSNA” (muscle sympathetic nerve activity) is how much nerve signaling there was during the head-down rotation:

They also estimated blood flow in the calf muscles by measuring how much the calves swelled, and found a similar pattern: triggering the otoliths with head-down rotation caused a reduction in blood flow to the calves by constricting blood vessels, but this response was suppressed after eight weeks of running.

The conclusion of the study is that it’s not fitness alone that alters your response to standing suddenly. Instead, there’s something specific to running’s up-and-down motion that seems to make your brain pay less attention to motion signals from your otoliths. This doesn’t mean it’s the only reason for headrushes, but it suggests that it’s one of them. It’s worth noting that the cyclists in this study were on stationary bikes, so it’s possible that real-world cycling might have a little more side-to-side motion that might have a similar effect—though you’d still expect it to be much less than from running.

As an aside, another situation where runners sometimes feel lightheaded and collapse is at the end of long races. This is also a situation where the heart is having trouble getting enough oxygen to the brain, and it used to be blamed on dehydration. But it generally seems to happen right after people stop running, which suggests that it’s actually a problem of blood distribution. When you’re running, your blood vessels are dilated, and the squeezing of your calf muscles with each step pushes blood from your legs back to your heart. When you stop running, your blood vessels are still wide open but this calf-muscle pump suddenly stops, so blood pools in your legs and you feel faint. The takeaway: keep moving after you cross the finish line.

As for the takeaway from the otolith study, it’s neat to understand what’s happening, and it’s somewhat reassuring to know that it doesn’t mean there’s something wrong with my heart or blood-pressure regulation. Is it a problem to have less sensitive otoliths? I’m not sure. I couldn’t find any evidence that runners have worse balance in general than other athletes or the general population. It would be interesting to see data on that. I’m also curious about whether there’s any link between how smooth your running stride is and how sensitive your otoliths are. If so, that might be the nudge I need to finally try to smooth out my notoriously (some would say comically) bouncy running stride. For now, I’ll just take my time getting off the couch.

For more Sweat Science, sign up for the email newsletter and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.

The post Why Runners Get Lightheaded When They Stand Up appeared first on Outside Online.