Chandler Bursey used to have an office. It was a modest room at the Veterans Affairs campus in Idaho, a set of buildings nestled under one of the mountain ridges reaching into Boise. The office, a meeting place for members of the union chapter Bursey leads, was something the union had negotiated. For many years it relied on VA resources, but after Donald Trump was reelected, Bursey began decoupling. “I made sure to separate all of our computer systems, get our own separate phone line,” he says. “He might kick us out.”

Like other federal labor leaders, Bursey spent the first months of Trump’s second term waiting for the other shoe to drop. The Heritage Foundation’s manifesto had called for the dismantling of public sector unions and privatization of various agencies. Within weeks of the inauguration, federal workers were already experiencing “trauma,” as Project 2025 architect and Office of Management and Budget chief Russell Vought had promised. But the first sweeping assault on the unions arrived in mid-March in an executive order clawing back labor rights across dozens of agencies. Bursey’s chapter was booted from its office—a minor ding next to the loss of hard-won guarantees of good working conditions and paid parental leave, which went out the window along with the workers’ collective bargaining rights.

The VA’s new political appointees issued a dubious statement, claiming taxpayers were losing millions of dollars as agency employees spent work hours on union activities. Bursey did set aside some of his day for union tasks, but given his $52,000 salary, the numbers didn’t add up. “We save the American taxpayer money,” he counters. “We see issues within the VA. We help them become more efficient.”

Not only that, but the administration had, in one fell swoop, squandered the considerable resources that went into creating that collective bargaining pact. “The government spent a lot of money with their attorneys to sit down and negotiate with the union,” Bursey says. “And then the government just says, ‘Yeah, it’s not real. I don’t believe in it anymore.’”

Across town, at Boise Airport, local Transportation Security Administration workers were staring into a similarly uncertain future. A few weeks before Trump issued his order, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem had announced she was canceling TSA’s collective bargaining agreement. “That’s kind of like my work bible,” says Cameron Cochems, who leads Idaho’s TSA union chapter. “But if the laws of the country are just kind of going away, then what’s stopping [workers’ rights] from just getting thrown in the trash can, too?”

Cochems’ and Bursey’s chapters both fall under the umbrella of the American Federation of Government Employees, the largest federal union. It’s been a busy year for AFGE’s lawyers who—alongside a handful of other unions—have filed eight lawsuits on their workers’ behalf. In July, a federal judge temporarily reinstated the collective bargaining agreement for TSA workers, pending a final decision. In the meantime, there’s little to do but wait. “A lot of the members, I felt, were kind of despondent about it,” Cochems says, “because they’re just like, ‘Oh, the union is so weak anyway, especially because we can’t strike.’”

Amid DOGE’s assault, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) went on a rant suggesting federal jobs are not “real jobs” and the workers “do not deserve their paychecks.”

Unless you’ve worked for the government (as I did until February of this year), you might be surprised to learn that striking is a felony for federal workers. The government had always cracked down on public sector strikes, but they were officially outlawed in 1947, made punishable by fines, jail time, and a lifetime ban from government work. Even asserting a right to strike—or belonging to an organization that does—can bring about those consequences.

Civil servants have staged illegal strikes in the past, but for decades, no one has dared run afoul of the laws, tranquilizing a once-militant workforce. “A lot of people think that since we don’t have the right to strike,” Cochems says, “we’re kind of like a paper tiger.”

Lately though, federal unions have been showing they are still relevant. Take Adam Larson, who a few years ago was “voluntold” into a leadership post with the National Federation for Federal Employees (NFFE) chapter for Idaho’s Forest Service workers. As Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) began bulldozing agencies with zero transparency, Larson’s nascent presidency shifted into high gear, his chapter becoming a key source of information and support. “No one knew anything. The [Forest Service] wasn’t sharing any information with us,” Larson recalls. “I was like, ‘Yeah, this is a tough situation. Here’s what we know. We’ll share more when we find it.’”

The workers were grateful to hear from someone. The chapter organized dinners for targeted employees and helped people share their stories with news outlets. Bursey and Cochems conducted their own triage operations, orchestrating pickets against the mass firings and, more recently, mounting food drives for essential workers unpaid during the shutdown.

This mutual aid has been a lifeline for many, even if it doesn’t solve the bigger problems. Under the anti-strike laws, big-ticket negotiations became the purview of national union leaders, not local chapters. The result is “a quieting of on-the-ground work, because I think a lot of members are just like, ‘Oh yeah, they’ll take care of that at the higher levels,’” Larson says. “Decades of that have kind of declawed us.”

The public sector has a much larger share of unionized workers than the private sector, but the rights of the civil servants have lagged far behind. Since the 1930s, federal laws have allowed private sector employees to unionize and strike, but it would be decades before federal workers could even bargain as a unit.

A few piecemeal laws and executive orders were solidified into the 1978 Civil Service Reform Act, which lays out federal workers’ limited rights. Their unions cannot bargain over pay and benefits, for example, because those pertain to federal spending—congressional turf, even though Congress has all but ceded its spending authority to Trump. Unions may negotiate how employees are classified within the rubric that determines salaries, but other restrictions are spelled out clearly, including the criminalization of strikes. (Most states also prohibit state and local government employees from striking, and about a third forbid public sector collective bargaining.)

The rationale for these restrictive laws is that allowing civil servants to strike would give them—relative to other citizens—unfair influence over government. By threatening work stoppages, they could sway policies and influence how tax dollars are spent. And because their services are often essential—think air traffic controllers—the ability to strike would make unions “so strong politically, the mayor of the town will always cave to the striking union,” explains Joseph Slater, a professor of law at the University of Toledo and an expert on public sector labor. That’s the theory, anyway. Slater is unconvinced.

“I think that concern is largely misplaced,” concurs Kate Andrias, a Columbia Law School professor who specializes in labor and constitutional issues. In countries and states where civil servants are allowed to strike, “there really hasn’t been a history of or a demonstration of circumstances where workers routinely abused that power.”

“I could make more in the outside community doing what I do, but I believe in the mission of the VA.”

That’s partly because striking demands sacrifice. “The difficulty of actually going on strike and losing a paycheck is a very significant check on the ability of workers to go on strike,” Andrias says. Government workers, by and large, are not highly paid, so a strike is a big ask that most workers won’t agree to unless the outcome is vital.

The public benefits, too, when federal workers are well-treated. The ability to negotiate fair pay and benefits results in lower turnover and a more experienced workforce, which in turn delivers better services—although that perspective contrasts sharply with Republican rhetoric depicting civil servants as acting against the public interest.

Amid DOGE’s assault, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) went on a nonsensical tirade suggesting that federal jobs are not “real jobs” and federal workers “do not deserve their paychecks.” Such sentiments were pervasive long before Trump’s minions started kneecapping the federal workforce. In a May 2024 proposal to reduce federal employee benefits, House Republicans asserted, “The biggest losers in this system are hardworking taxpayers who are forced to subsidize the bloated salaries of unqualified and unelected bureaucrats working to force a liberal agenda on a country that does not want it.”

Pay stubs tell a different story. According to an analysis of 2022 data from the Congressional Budget Office, federal workers without a college degree tend to make a bit more than they would in similar private sector roles—perhaps because less-educated workers are more likely to be shortchanged by private employers—but people with advanced and professional degrees earn significantly less than their private sector counterparts. “I could make more in the outside community doing what I do, but I believe in the mission of the VA,” Bursey says. “When they’re saying we’re taking millions of dollars away from the American taxpayer, that’s not true.”

Historically, civil servants have leveraged their collective bargaining power and risked strikes to, at least in part, actively improve government services. “The piece that people don’t appreciate is that they are purpose driven. They’re there to serve the public,” Max Stier, CEO of the nonprofit Partnership for Public Service, told one of my Mother Jones colleagues. “They are not clock watchers. They’re not lazy,” he adds. “If they’re in NASA, it’s because they want to explore the universe. If they’re at the VA, it’s because they want to serve veterans.”

Trump’s attempt to destroy the much-maligned “administrative state” have already succeeded in making government less effective and less responsive to people’s needs. The onslaught has, among other things, harmed the ability of already strapped federal agencies to collect weather data; compile key agricultural, economic, and housing statistics; conduct scientific research; and respond to climate disasters. Former IRS chief John Koskinen predicted that the gutting and demoralization of that agency’s staff will likely result in a disastrous upcoming tax season—with significant revenue losses thanks to the summary firing of sophisticated auditors and enforcement personnel.

“People think that we’re just focusing on ourselves. That’s not the case at all,” Cochems told me. “We’re focusing on making the country a better place for all of us.”

I heard this sentiment from every labor scholar and leader I spoke with, but it’s a message that demands a receptive audience. Notes law professor Slater: “It is not at all clear that anybody in the Trump administration believes that argument or even cares tremendously about certain agencies functioning well.”

Many legal experts see a strong First Amendment case for the right of public sector workers to strike, because what is a federal strike if not people exercising their rights to speak, assemble peacefully, and petition the government for grievances?

The Supreme Court has broadly protected the right of workers to unionize, but it has yet to extend First Amendment protections to union activities. One one hand, “there’s never been a Supreme Court case squarely saying you don’t have a right to strike,” Slater offers, but “given our current Supreme Court, I doubt that’s going to change.”

A legal precedent exists for stripping union protections from certain agencies, but Trump has stretched it to the extreme. The Civil Service Reform Act states that a president can revoke collective bargaining rights from workers handling serious national security matters. In the past, the stipulation has been applied only to agencies like the CIA, but now, “Trump is basically saying most of the federal government does that,” Slater says. “That’s an extremely aggressive interpretation.”

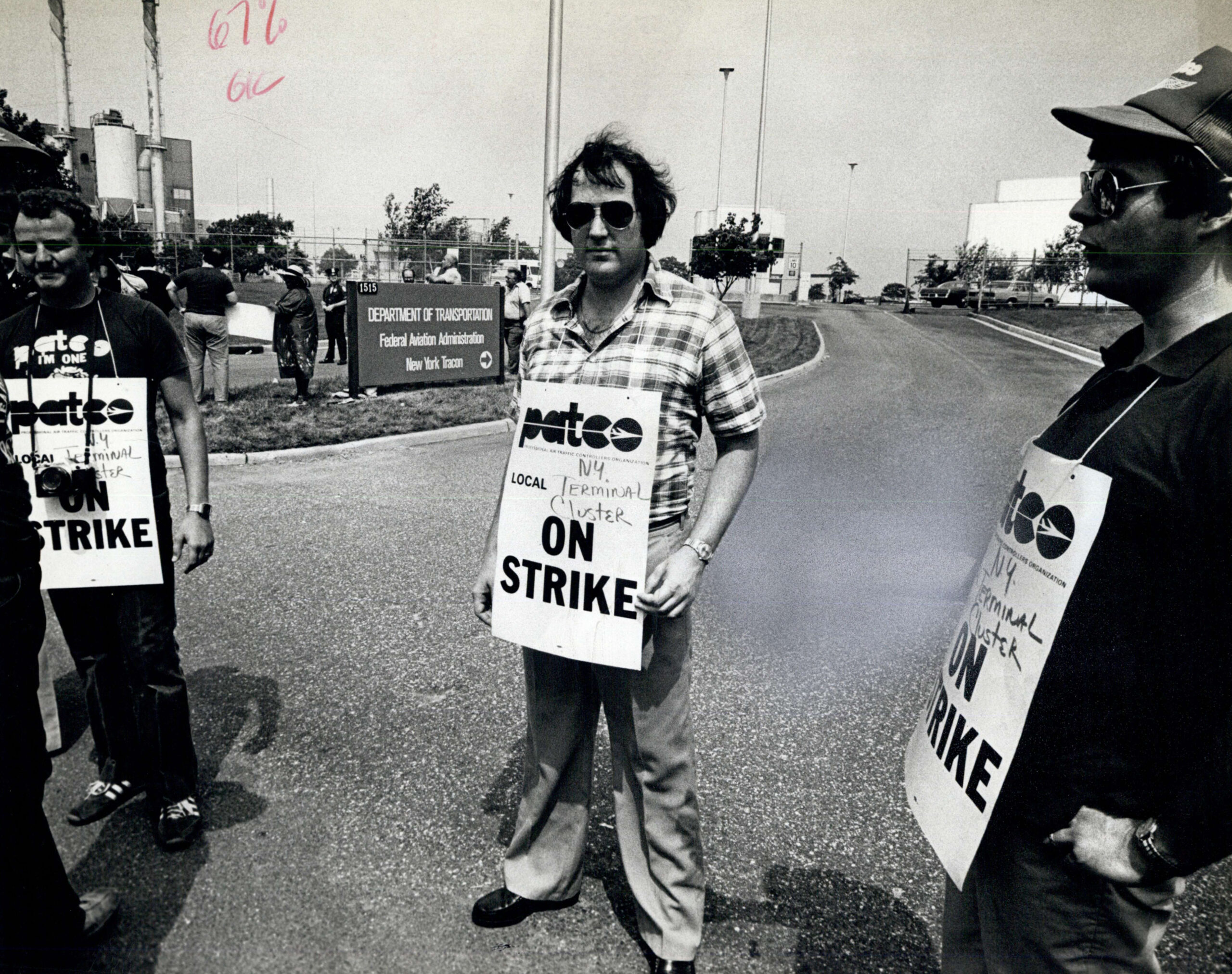

When air traffic controllers launched their illegal strike in 1981, “everything unfolded fast…The government really brought down a sledgehammer.”

The administration claims the national security provision pertains to everything from the Department of Justice to obscure agencies like the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. Unions are fighting back in the courts, but that’s a path available for only the most paramount of grievances. For other labor disputes on Trump’s watch, workers are out of luck.

Barred from striking, federal unions are left with arbitration, the highest level of which goes through the 10-member Federal Services Impasses Panel. This is where civil servants are supposed to turn when negotiations are gridlocked—the point at which nongovernment workers might walk off the job. FSIP is staffed by presidential appointees, typically labor rights experts like Slater, who served on the panel under President Biden. A shuffling of panelists is normal when a new administration comes in, but early in his second term, Trump basically nuked the panel—every seat has been vacant since February.

Government bodies tasked with resolving lower-level disputes—such as the Merit Systems Protection Board—have been similarly and “intentionally” disabled, Slater says. And those mechanisms are especially important now, given the deteriorating relationships between federal workers and their bosses.

When Trump’s people came in, “I saw a massive shift in the tone in which upper management was speaking to the union and started treating [VA] employees,” Bursey says. “That’s been really hard to watch.” He’s heard managers assert that union posters in agency hallways constitute propaganda. In such an environment, it’s hard to imagine resolving any clashes amicably.

And now there’s nowhere to turn.

There’s a union slogan that was common in the 1960s and ’70s, when public sector strikes were tolerated for a time: There are no illegal strikes, just unsuccessful ones. Many of the rights public sector employees have today were the product not of lawsuits and arbitration, but of illegal strikes by teachers, sanitation workers, and federal employees. In response, states began to recognize the labor rights of their own civil servants, which eventually led the federal government to establish union rights for its workforce.

Things were looking up for organized labor. And then came the PATCO fiasco.

On the morning of August 3, 1981, 13,000 air traffic controllers walked off the job. They demanded better pay and shorter hours, as increased air travel was straining the workforce and causing safety concerns. The Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization had been in a stalemate with the Federal Aviation Administration for years, and union leaders began planning an illegal strike. When the controllers finally stepped off the job, “everything unfolded fast,” says Joseph McCartin, a professor of labor history at Georgetown University and author of Collision Course, a book about the PATCO strike. “The government really brought down a sledgehammer.”

They were on the picket line only a few hours when President Ronald Reagan, in a televised press conference, gave the controllers 48 hours to return to work or be fired. Reagan’s attorney general announced he would start filing criminal charges as early as that afternoon. No federal employees had ever been charged for striking before, and the workers held strong. But Reagan didn’t cave. He fired 11,000 air traffic controllers, the union was decertified, and PATCO leaders served jail time.

The move sent shockwaves through the federal workforce and ushered in an era of union-busting that has broadly reduced the power of labor. Strike activity waned in the private sector, and there hasn’t been a federal strike since. “You see what happened to the PATCO workers, and one might imagine an even more aggressive stance by the Trump administration,” Slater says.

“Russell Vought said that he wants to make our lives miserable and so knowing that…has really engaged a lot of people.”

McCartin views things differently. “I fear that some of the leaders of the federal unions really almost took the wrong lessons from the PATCO strike,” he says. After all, the controllers had some major factors working against them in 1981. They’d threatened to strike long before it happened, giving the government time to bring in military personnel who were qualified to manage the airspace and willing to cross picket lines.

More importantly, the union didn’t have the public on its side. While some of the controllers’ demands involved public safety, they sought a $10,000 raise (almost $36,000 today)—an off-putting amount when many Americans were feeling the squeeze of an impending recession. What’s more, Reagan, PATCO’s adversary, was a popular president who had just survived an assassination attempt, rocketing his favorability ratings above 70 percent.

If federal workers went on strike today, they might receive a more sympathetic hearing from a public who saw them in line at food banks during the shutdown. Today’s villains are more clear-cut, too: a government that aspires to put its own workers “in trauma,” as Vought phrased it, and is openly corrupt to boot.

“We are not allowed to take anything while we’re on duty in our official capacity, even a candy bar,” Cochems says. “But then we see videos of people in elected offices in the White House basically swimming it up with cryptocurrency kings. All these people are making millions of dollars or getting a $40 billion plane…or whatever the hell—in their official capacity.”

Given all of this, previously disinterested employees are warming up to collective action. As DOGE hacked agencies apart, union sign-ups spiked. In February, AFGE announced the highest number of dues-paying members in its history. More than 14,000 people joined the union in the first five weeks of 2025, about as many as it had gained the entire previous year. “They say that the boss is the best organizer,” Larson explains. “Russell Vought said that he wants to make our lives miserable and so knowing that that’s coming down the pipe has really engaged a lot of people.”

But the mass layoffs put a dent in union membership. Since January, the government has shed an estimated 10 percent of its civilian workforce, with some agencies and union chapters much more heavily gutted. “Most of my department took the deferred resignation program after months of getting illegally fired and then rehired and then treated like hot garbage,” Larson told me, his own Forest Service team having shrunk from 10 workers to three.

Many workers opposed their national unions urging Democrats to end the shutdown: “We were willing to suffer a little bit longer to make sure that the greater good was achieved.”

Trump’s sweeping anti-union order also decimated union membership; federal payroll systems stopped collecting the dues that are normally deducted from members’ paychecks, which many workers only realized upon scrutinizing their pay stubs. Without knowledge or consent, they’d been dropped from the rolls.

“We’re steadily getting them back, and we’re steadily losing people,” Bursey says. “That was hard to take.” He and the other leaders have worked so hard to build up their membership over the past few years, only “to see it just rapidly decline, pretty much overnight.”

Bursey now believes someone in his regional office management has been spreading false rumors that the union is kaput. Members call him up, saying, “I want to drop. You guys don’t exist anymore,” he says. “My first response is, ‘How did you get ahold of me? The union cellphone! We’re still here!’”

The compounding indignities have led more union chapters to seek safety in numbers. Bursey and Cochems have been collaborating with other Idaho-based workers, including Larson’s NFFE chapter. “We’re all in lockstep,” Bursey says.

The Federal Unionists Network, which started out a few years ago as a WhatsApp group chat, has evolved into a government-wide worker collective. They distribute information and resources and mobilize federal employees to turn out for national protests like “No Kings,” as well as local actions.

A picket line of workers who will still clock in isn’t as disruptive as a strike, but it’s more energizing, and visible, than lawsuits and arbitration sessions. Everyone can participate. “Cameron [Cochems] has been coming out to our pickets 100 percent of the time,” along with every registered Democrat in Boise, Bursey jokes. “There’s not many, but they’re feisty, let me tell you.”

During our video call, Cochems points to a sign on his wall reading Solidarity! Solidarity! Solidarity! This ethos transcends unions, he says. Federal workers are increasingly feeling more in solidarity with the public than with their national union leaders. When Everett Kelley, AFGE’s national president, asked Congress to end the shutdown four weeks in, many workers interpreted it as a call for the Democrats to cave. And when the NFFE applauded the Senate for passing a resolution that failed to extend the Obamacare subsidies, as Democrats had demanded to keep health insurance affordable, a lot of federal workers felt betrayed. “I’m definitely angry about it, because I’ve seen the people that were suffering for it, but like, We’re going to get that to get that health care,” Bursey says. “We were willing to suffer a little bit longer to make sure that the greater good was achieved.”

There are indications that the administration’s union-busting may have gone further than the public is willing to stomach. Last week, 20 House Republicans joined Democrats in passing a bill (the Protect America’s Workforce Act) that would reverse Trump’s anti-union executive order. The GOP showing may be performative—the bill faces greater obstacles in the Senate—but this at least suggests that vulnerable Republicans are getting an earful from constituents.

An illegal strike would be a last resort, of course, and many workers fear Vought et al would use it as an opportunity for further firings. Some civil servants, too, view striking as antithetical to their mission. At the VA, “we’re providing health care, so if we shut down in a strike, where’s that veteran going to go?” Bursey says. “To go on strike would kind of go against our own oath with the VA, but that doesn’t mean that we’re not going to fight.”

They are, in any case, growing impatient. The legal system moves excruciatingly slowly, and with mixed results. Many workers want to see action before it’s too late. “Every day could be our last day doing this,” Cochems says. “I just feel like I’m living on borrowed time.”

Taking action might just mean more picketing, and workers reaching out to members of Congress directly instead of trusting national union figures to lobby on their behalf. But the biggest goal is to win over the public. “I think everybody will get to a point where the American population is going to get so fed up with this that 7 million people for the No Kings protest is going to look like a trickle,” Bursey says.

“That’s what we’re working toward.”