In 1908, the writer Elbert Hubbard published a quiet declaration in the biography of Thomas Arnold, a teacher he admired. “He was only a schoolteacher. However, he was an artist in schoolteaching,” he wrote, “and art is not a thing. It is a way.”

It’s no surprise that so many outdoorspeople—and climbers in particular—are also artists. Both climbing and art demand the sort of reverence and attention to detail that can evade modern attention spans and inspire lifelong dedication—not to a thing, but to a way of existing. At nearly every climbing festival I’ve attended, I stopped by dozens of booths containing handmade art that makes me feel seen precisely because they only make sense to climbers. Think: carabiner-shaped earrings, figure-eight necklaces, keychains in the shape and colors of my favorite climbing shoe. And prints, dozens of them; wild places given depth on the page.

For some climbers, art is both a way of life and an important source of income. Salomé Aubert, PhD, is a climber who lives in Avignon, in the south of France—a region she calls a “paradise” for sport climbing. By trade, Aubert is a population health expert in the study and promotion of physical activity. However, she also creates and sells her climbing-inspired designs for a living while she waits for the right position to open up. From her online shop, she ships out prints and stickers, features her art in a Gorp Garb clothing line, and promotes her digital designs to a community of 43,000 on Instagram. (She’s also illustrated for Climbing.)

Last year, in May 2024, Aubert came across a disturbing post on a public, anonymous Instagram page. It was inexplicably her drawing. And something was off.

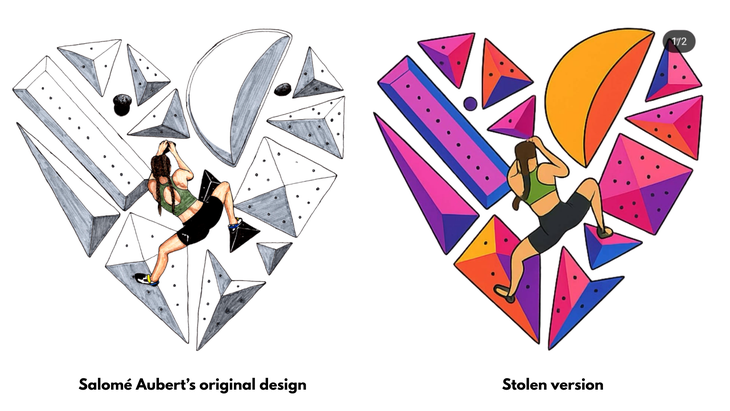

In the drawing, a brown-haired female climber high-steps a volume and matches a crimp in a group of plastic holds that form a large heart shape. The climber wears a green, halter sports bra, black bike shorts, and two-toned climbing shoes.

But a few details were different. Aubert’s delicate shading had been replaced by solid color fill. The edges of the shoes, bra, and holds had been simplified. And instead of French braids, the climber sprouted a single brown tuft of hair. It looked more like a leopard tail than human hair, and it curved unnaturally into her armpit.

Aubert knew, then, that her art had been copied by someone with the help of AI.

“Tag a climber who needs this shirt,” the caption said. “Order yours from our store. The link is in bio.” The link in bio took her to a store, which sold the AI version of her design on everything from t-shirts for $19.95 to hoodies for $39.45.

In the past three years, the explosive popularity of cheap, text-to-image generation programs such as Midjourney, Adobe Firefly, and Stable Diffusion—all trained on the copyrighted art of unconsenting artists—has shrunken the market for human creations. Forbes reports that 71% of images on social media are now AI-generated; more than 34 million AI-generated images are created every day.

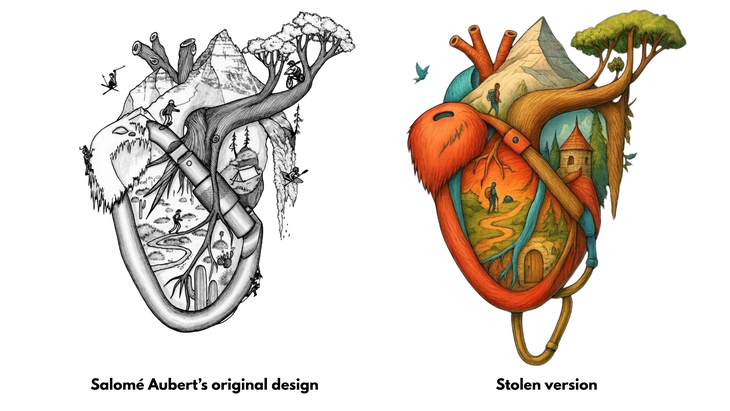

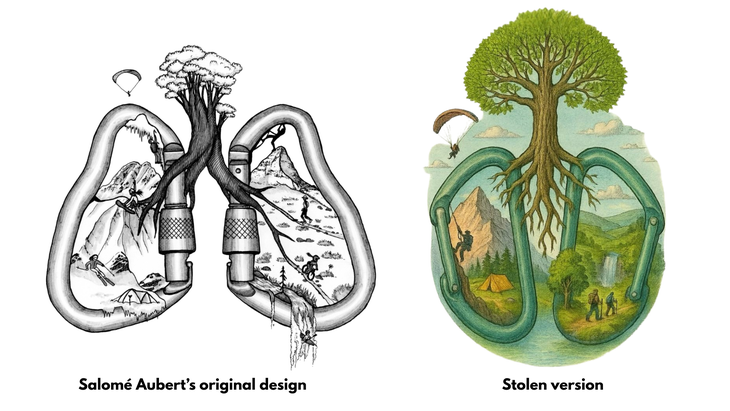

Aubert’s art is the kind that plain AI generation cannot easily replace; her designs often blend the natural and surreal in subtle layers. In the design above, for example, she weaves tree roots into arteries and includes a locking carabiner in the rough shape of a human heart. It’s a difficult concept to describe in an AI prompt without using her image as an exact reference.

But it’s extremely easy to steal. AI-generated art has opened up a new type of theft called style mimicry, in which people use the artist’s name in the AI prompt in order to generate new images in a replica of that artist’s style. For Aubert, the extreme similarities between her original designs and the AI-generated versions made the mimicry obvious.

So what can she do about it?

I spoke with Professor Yvettte Liebesman, a member of the American Law Institute, 18-year law professor, and the founding director of the Intellectual Property Concentration Program at the St. Louis University School of Law, to ask exactly this.

(Note: The following is not legal advice.)

9 Things to Know Before Your Art Gets Stolen by AI

1. Unauthorized copying of art is illegal—yes, even with the help of AI.

“As soon as your original work is fixed in a tangible medium of expression, you own copyright in that work,” says Professor Liebesman. This means as soon as you save your design on your computer—meaning, it exists for a period of time—you own the copyright.

But copying art is not usually a crime. The copyright owner’s remedy is a civil action, meaning you sue them but don’t file criminal charges. And it’s the person who used the AI who infringed, not the AI itself.

2. Even if AI is used to alter your work, it can still be illegal.

“The courts don’t want people to be able to get away with infringement by just making minor changes,” the professor adds.

A copyright owner of a piece of art usually has four enforceable rights: reproduction, adaptation, public distribution, and public display. For the artist, the one that usually must be proven first to enforce any or all of these is infringement of the reproduction right. The other rights usually grow out of this one. For example, if someone sells an unauthorized copy of an artist’s work, that covers both reproduction and distribution rights.

If someone uses AI to steal your art, even if it’s not an exact copy, it can still count as copyright infringement of the reproduction right—if you prove two things in court. According to Professor Liebesman, the first condition has to do with whether the alleged infringer actually copied the artist’s work: the artist has to prove access and substantial similarity: (1) that the person you’re accusing had access to your work and (2) that the two works are substantially similar.

But that’s not enough. For the second condition, the artist has to prove what the alleged infringer copied was “protectible expression,” something the artist has the right to control. An artist can only protect their own original, creative expression. You also cannot monopolize nature.

For example, if two artists are both trying to draw a butterfly to look as real as possible, neither has a monopoly on what a butterfly looks like. Even if the second artist saw the first and then decided to draw their own realistic butterfly, it doesn’t matter how similar they are; it’s not protectible expression.

3. You need to register your work in order to sue.

Think you’ve got a copyright case on your hands? Unfortunately, a lawyer is unlikely to take up your case unless you’re going for at least as much as their lawyers’ fees will be.

“If you want to sue somebody, it’s expensive,” says Professor Liebesman. “And until you’ve registered your work with the copyright office, you can’t sue at all.”

Most people don’t register their copyright with the U.S. government, but it’s an important step. If you register after your work is stolen, you can usually only get actual damages, which are often very low. But if you register before the infringement, based on the timing of your registration, you can get statutory damages, which can be up to $150,000 per work that is infringed.

“You’re always better off registering,” says Professor Liebesman. She registers her own works either before she publishes or within a few weeks of publication, in order to best protect them under the law.

4. Registering your copyright is $65. You can do it online without a lawyer.

Next time you create art and want to publish it online, head to the U.S. Copyright Office website to register your art first. It costs $65, unless you’re bundling multiple works.

For many artists, this might be a pain, but consider the tradeoff: By registering as soon as you publish your art online, you’re getting access to up to $150,000 if someone steals your copyrighted work.

The process can take between 20 and 40 minutes, and you don’t need a lawyer to complete it. Even if the art is already published, you should still do it as soon as possible.

If you wait too long to register after publication, you may only be able to sue for actual damages, which are only substantial if the infringer has made a lot of money off of your work.

5. Dissuade art thieves by displaying proof of registration.

It’s not enough to say that the work is under copyright; all fixed original expressions are. But having that registration displayed indicates that if your art is stolen, you’re serious and capable of taking legal action.

“Just by saying on your website, ‘Copyright registration applied for,’ that will signal to them, ‘Oh, crap. If we copy this, we could be hit up for $150,000,’” says Professor Liebesman. “Having that registration is always a great signal. ‘Works displayed here all have copyright registered with the U.S. Copyright Office.’”

6. Send a takedown notice.

Regardless of whether you registered with the copyright office, you can still get your stolen work taken down from the website that hosts it through the Digital Millenium Copyright Act (DMCA).

“Every site should have a place where you can send a takedown notice,” says Professor Liebesman. “In order to not be sued under what’s called a safe harbor, what [the DMCA] says is that if I tell you that this work someone has put up is infringing on my copyright, you have to take it down. Then, once it’s taken down, the alleged infringer has the option to rebut it and provide evidence to counter that.”

If your art is being sold online, look at the bottom of the page or the main menu to find where you can send a takedown notice. You don’t need a lawyer to do this, either.

7. Non-American artists are protected, too.

Thanks to the 1886 Berne Convention, foreigners from any of these 182 countries are afforded the same copyright protections as U.S. citizens, and vice versa.

“The U.S. was one of the last countries to sign, about 100 years after everyone else,” says Professor Liebesman. “What the treaty says is we protect that copyright of people who create in other countries who are members of the treaty.”

This means that Aubert’s designs, even if she creates them in France, are still protected from Americans who might steal them.

8. While U.S. laws can’t be enforced abroad, international law is complex, and you may be able to sue in other countries.

In the past, Aubert has found her designs—sometimes the AI versions, sometimes just regular copies—being sold on TEMU, a site based in China. Thanks to the Berne Convention, U.S. copyright law does apply to Aubert’s art, and this treaty allows artists to sue for infringement under the laws of other member countries. This is a very complex area of law, and you’re best off reaching out to a lawyer to navigate it.

Still, many foreign websites may offer a space to send a takedown notice. Professor Liebesman encourages sending this. “It’s easy; it never hurts,” she says.

9. Try free AI “cloaking” software before you post your art.

In March 2023, a group of PhD students and computer science professors from the University of Chicago released a free software called Glaze, which subtly alters an image in a way that stops the image from being easily copied by AI.

Check out this Q&A to learn more about how it works.

The post AI Is Coming for Your Nature-Inspired Art. Here’s How to Fight Back. appeared first on Outside Online.