When legendary sports scientist Carl Foster was honored by the American College of Sports Medicine last year, he was asked which among his 570 peer-reviewed publications was his favorite. He singled out an obscure 2001 study in an even more obscure venue, the South African Journal of Sports Medicine.

The study was simple. He asked a group of college runners to keep track of how hard each day’s training was for five weeks, and compared their responses to how hard their coaches intended them to train. The results revealed a consistent pattern: when the coaches told them to go easy, they went harder than intended; when they were told to push hard, they ran easier than they were supposed to.

This regression to the middle says something interesting about human nature, and may help explain why so many athletes end up stagnating or overtraining. But it also highlights a more basic problem: it’s very difficult to accurately communicate how hard you want someone to exercise.

That’s the backdrop for a major new initiative from the American College of Sports Medicine (along with their counterparts in Australia). An international group of 16 experts led by Victoria University’s David Bishop has just put out a consensus statement in the ACSM’s flagship journal, Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, on “Physical Activity and Exercise Intensity Terminology.” In short, they want everyone to agree on exactly what we mean when we say “Go easy today,” or “Make this next rep really hard.”

The task is harder than it sounds, because Bishop and his colleagues hope to unite some very different worlds: public health, exercise, sport, and elite performance. And they hope to provide terminology that applies equally well to aerobic exercise and strength training. It’s a big ask, and they’re well aware that each of these worlds already has their own terminology that they won’t give up easily. But at the very least, the consensus statement aims to provide a universal key that will enable people to translate between the different worlds: between public health guidelines calling for “light” exercise, scientists talking about “severe” intensities, personal trainers prescribing sets at 80 percent of one-rep max, online gurus recommending “zone 2” training, and so on.

What the New Guidelines Say

I’m going to jump straight to the punchline. Here are the five zones suggested by Bishop et al.: Very Low, Low, Moderate, High, and Very High. The sense of effort you should perceive in these zones is, respectively: very easy, easy, somewhat hard, hard, and very hard. Seems pretty straightforward so far. You can argue about whether calling something “high” instead of “heavy” or “severe” is a significant advance, but there’s something to be said for having consistent terminology across disciplines.

Now comes the hard part: How do we distinguish between these various zones? Ideally you want some distinct and measurable difference in physiological response that makes one zone different from another.

Aerobic Exercise

For aerobic exercise, the most obvious candidates are our metabolic thresholds. I wrote an article a few years ago digging deep into the meaning and definitions of the term “threshold.” The key takeaway was that there are actually two thresholds, each marked by subtle changes in your breathing, lactate accumulation, and general ability to keep going. There are several different names for these thresholds: the first one is often called lactate threshold, and the second one is often called critical speed. Bishop and his colleagues keep it general and just refer to the first and second metabolic thresholds.

The first metabolic threshold is the divider between Low and Moderate exercise. The second metabolic threshold is the divider between Moderate and High exercise. In a simpler world, these three zones might be enough. But for some purposes, it’s useful to have a separate definition for Very Low and Very High intensity.

The marker they suggest for Very High intensity is somewhat convoluted. It corresponds to the highest running speed (or cycling power or whatever) you reach at the end of a VO2 max test. In practical terms, this is a pace you can likely sustain for only a few minutes at a time. On the other hand, there’s no physiological marker at all for Very Low intensity. Given that getting sedentary people to do even a little bit of exercise is an important public health goal, the authors figured they needed to have a Very Low category, but for now it’s only hazily defined compared to the Low category.

Other Ways of Defining the Zone Boundaries

Equally significant is how they’re not defining the zones: no percentage of max heart rate (or variations like heart rate reserve or percentage of VO2 max). Even though max heart rate-based training remains popular in practice, there’s a large body of research showing that it’s too imprecise to be practical. If you tell a group of people to exercise at, say, 80 percent of their max heart rate, it will be easy for some, moderate for others, and extremely hard for a few. Basing the zones on metabolic thresholds produces a much more consistent stimulus: it will feel similarly hard (and produce similar physiological stress) in everyone.

Of course, not everyone knows where their metabolic thresholds lie, and not everyone wants to visit an exercise physiology lab to find out. I’ve always been a fan of the Talk Test to approximate the thresholds: if you can talk in complete sentences, you’re below the first threshold; if you can speak in short phrases with a bit of effort, you’re between the two thresholds; if you’re down to a word or two at a time, you’re above the second threshold. Bishop et al. aren’t convinced the Talk Test is accurate enough, especially for the border between Low and Moderate, but acknowledge that it could be useful as a way of ensuring that you stay below the High zone.

It’s also possible to use your subjective perception of how hard you’re pushing as a guide. There are two commonly used versions of the “rating of perceived exertion” (RPE) scale, one running from 6 to 20 and the other from 0 to 10. On the 10-point scale, Very Low is below 2, Low is 2 to 3, Moderate is 4 to 5, High is 6 to 7, and Very High is 8 to 10. This approach is most useful if you’ve calibrated your sensations against some objective data (with a lab test of metabolic thresholds, say) so that you know what 6 out of 10 effort is supposed to feel like.

What About Strength Training?

Strength training is often described as a percentage of one-rep max, which is the heaviest weight you can lift once for a given exercise: do eight reps at 80 percent of one-rep max, for example. But this approach has the same flaw as max heart rate—the resulting stimulus varies too much from person to person—and is also meaningless for bodyweight exercises like push-ups or pull-ups.

Instead, the new guidelines advocate using the “reps in reserve” (RIR) approach, which is based on how many more reps you think you could have done after the point at which you stopped. If you have more than 8 RIR, that’s Very Low intensity; 7 to 8 is Low; 4 to 6 is Moderate; 2 to 3 is High; and less than 2 is Very High.

Research on the RIR approach is still relatively new, but the idea is that it gives a more reliable gauge of the physiological stress you’re imposing on your muscles. Of course, like perceived effort, it takes some experience to calibrate your RIR scale. How can you know how many reps you have in reserve until you’ve pushed all the way to failure at least a few times?

Does This Really Matter?

I mentioned Carl Foster’s paper on athlete-versus-coach perceptions at the top. To Foster, this disconnect was a profound revelation. “It explained overtraining syndrome in a second,” he said. For anyone training for competition, the benefits of getting the training intensity just right—not too hard, but not too easy either—are obvious.

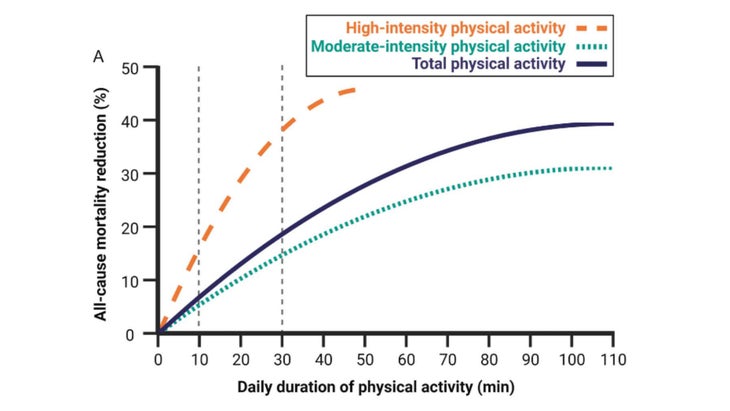

But I was also struck by a figure that Bishop and his colleagues included in their paper. For public health purposes, my general view is that getting people to do anything is a significant victory. That may be true, but it doesn’t mean that all exercise is equal. Here’s the figure, showing how much you reduce your chance of premature death with different intensities of exercise, based on data from a 2011 paper in The Lancet:

What this graph shows is that different intensities of exercise aren’t interchangeable. No matter how much moderate-intensity exercise you do, you’ll never get as much of a mortality benefit as if you include some high-intensity exercise. Conversely, prolonged high-intensity exercise carries more risk of injuries and other adverse events. Figuring out how to mix different intensities, and in what amounts and proportions, is the art of training. No one has the final answers on how to do this, but agreeing on what our words mean seems like a good start.

For more Sweat Science, sign up for the email newsletter and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.

The post The New Rules of Training Intensity appeared first on Outside Online.