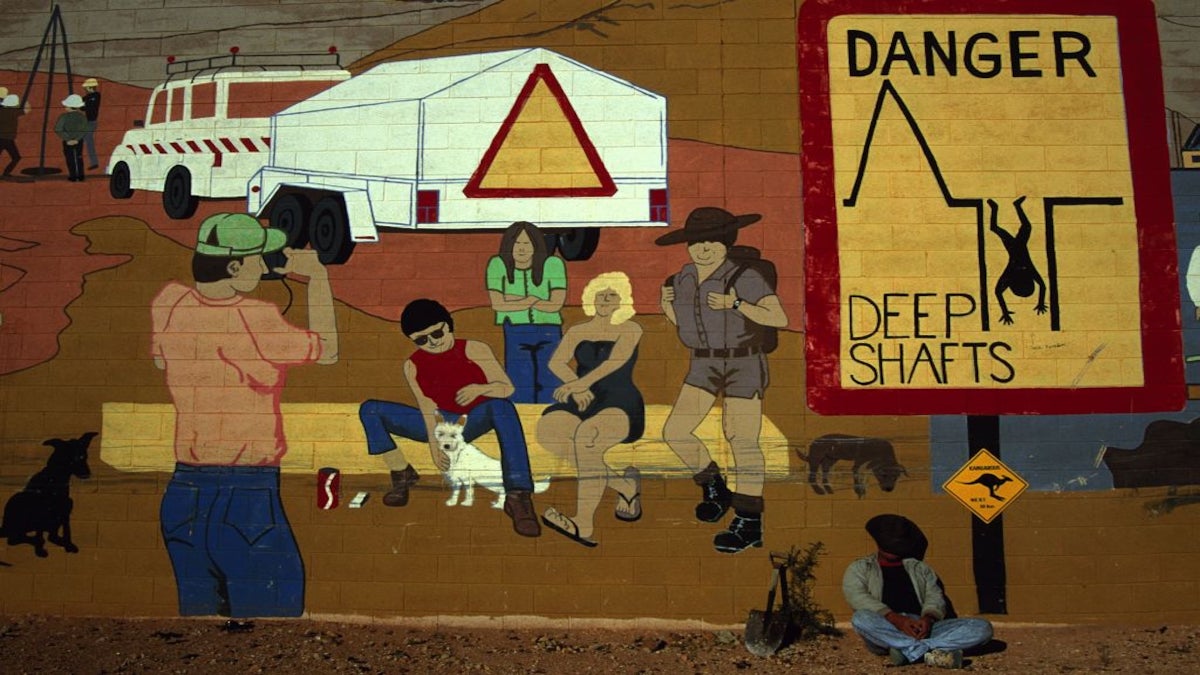

A Colorado woman who fell to her death after stumbling into a vertical mineshaft while hiking has highlighted a potential hazard that lies beneath our feet.

On October 20, Jennifer Nelson, 54, slipped into a hidden mine shaft near Spirit Gulch, in Uncompahgre National Forest just outside of Ouray, according to the Ouray County Plaindealer. Nelson, who was hiking with dogs, was reported missing when she didn’t return that night.

Rescuers later found Nelson inside a water-filled mineshaft roughly eight feet wide. Her body was floating atop the water, some ten feet below the opening of the shaft, but rescuers said it’s unclear how deep the shaft goes. The opening was also extremely difficult to see.

“Unless you walk right on top of it, you’re not going to find it,” Pasek said to the Ouray County Plaindealer.

As unusual as the incident may seem, it’s far from an anomaly. Reports indicate that there are an estimated half-million abandoned mines across the United States, many undocumented, and hikers, ATVers, and other outdoor enthusiasts are rescued from mines every year.

Colorado is home to over 23,000 inactive mining sites, according to The Colorado Sun. Although some 14,000 of these abandoned mines have been formally closed and marked off since 1980, many are still unmarked, and the locations of some, like the mineshaft Nelson fell into, aren’t even recorded.

“Some we know about, some we certainly do not, just because in these historic mining areas, time changes things as well,” Jeff Graves, program manager for Colorado’s Inactive Mining Reclamation Program (IMRP), told the outlet. “A feature may not be visible at the surface because it was covered in timber, and over time that timber rots, and suddenly now there’s a new feature, or the ground collapses, and something exposes its surface.”

The IMRP, which is funded by reclamation fees paid by active coal mines, says it costs an average of $5,000 to close a hazardous abandoned mine feature.

But Colorado is far from the only state with abandoned mines. The U.S. Department of Labor’s Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) estimates there are roughly half a million vacant mines across the country.

In November 2024, a man sustained substantial head trauma after tumbling 50 feet into an abandoned mineshaft in Hamlin Valley, Utah. A 19-year-old college student was rescued in 2021 after falling into an abandoned mine shaft on a trail outside of Boulder, Colorado. The same year, a 30-year-old man slid some 150 feet into a derelict copper mine near a popular ATV track in Vermont. He was rescued a few hours later, “considerably hypothermic.”

In 2018, first responders rescued a man who had fallen into a 100-foot-deep shaft inside a gold mine in western Arizona. The man, who was in his sixties, survived for two days at the bottom of the shaft without food or water. The year before, a man riding a UTV fell 90 feet into a mine shaft near Five Mile Pass in Utah.

Abandoned mines pose dangers beyond simple falls, too. The MSHA notes that vacant mining sites can contain leftover explosives and toxic chemicals, as well as potentially fatal levels of carbon dioxide and noxious gases such as methane, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen sulfide. The extensive, complex layouts of abandoned mines can also cause individuals to become disoriented and lost, and the decaying wooden supports that prop up many abandoned mine shafts frequently collapse without warning. Mines are also often home to bears, mountain lions, snakes, and other dangerous wildlife.

A review conducted by the online platform Geology.com counted reports from newspaper articles and found that some 278 individuals died in abandoned or otherwise inactive mining sites between 2001 and 2017. The vast majority of these deaths (201) weren’t from falling, however, but from drowning. The high number of drownings is primarily attributed to people intentionally entering flooded open-pit mines and quarries to swim, underestimating the dangers of freezing water temperatures, electrical currents, submerged machinery, and steep, slippery, or loose walls that can make exiting difficult or impossible.

However, cases like Nelson’s—accidental falls into flooded vertical shafts—also contribute to this tally.

The actual number of fatalities is likely higher than research indicates.

Although historical inventories from federal agencies like the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management can help his group identify abandoned mining sites, they also rely on tips from the public, Graves told The Colorado Sun. On average, Colorado state officials become aware of ten vacant mining sites each year simply through public tips.

“We can’t be everywhere all the time, so we really hope, and kind of rely, on the public to provide us information on sites that they are aware of in their wanderings,” he said. “Reach out to us so that we have an idea of what’s going on, so we can address these things before they come up, before they become a problem.”

The post A Hiker Vanished in Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. She Was Later Found Dead in a Forgotten Mine. appeared first on Outside Online.