The entrepreneurs who are part of the booming school safety industry face a cruel irony: they are dependent on the uniquely American epidemic of school shootings.

“Every time there is a shooting, we see an uptick in business,” says one, featured in the new HBO documentary Thoughts and Prayers, who sells bulletproof wall art and skateboards. “Every time there is a tragedy, it economically benefits my family. That’s not what I wanted. We could be a $300 million company by the time this documentary airs.”

There are, as the documentary shows, bulletproof desks that can double as shields, blackout shutters to block visibility into classrooms, and video game simulations that test how teachers respond to a fake threat of a school shooter. The school safety industry has become an estimated $4 billion juggernaut, aided in part by a $1 billion infusion from Congress in 2022 to support mental health services and infrastructure upgrades, instead of meaningful gun reform.

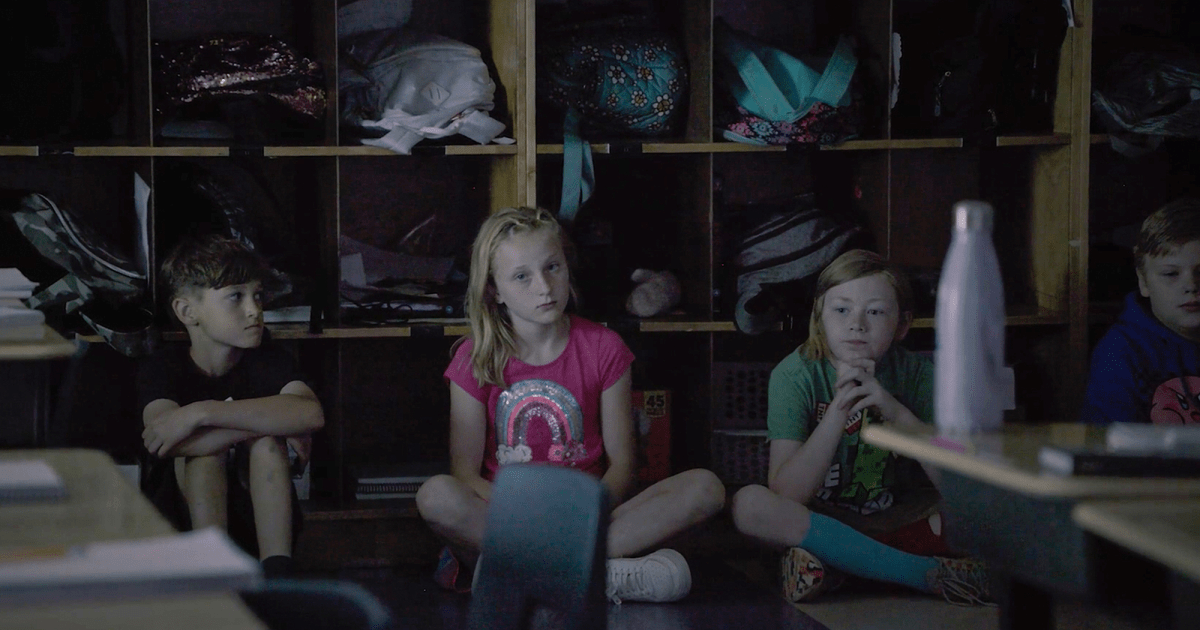

Despite the documentary’s critique of the American gun culture that has given rise to mass shootings, political debates and depictions of gun violence are absent from the film. Instead, there are sit-down interviews with teachers reluctantly learning how to shoot guns and kids learning to live with the looming threat of mass shootings. The filmmakers were also present for lockdown drills and a highly realistic mass casualty simulation at a school district in Oregon that included volunteer students portraying gunshot victims. For co-directors Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari, the goal of making the documentary was to “look at what people are trying to do” to combat mass shootings, Dimmock told me, “and ask the audience to consider whether or not this is going to work. And do we want to live like this?”

I spoke with Dimmock and Canepari by Zoom on Monday to discuss their approach to making the film, the limits of the products they highlight, and what they learned from the kids they spoke to.

This interview has been lightly condensed and edited.

The film implicitly critiques these school safety products while also taking an earnest look at how they’re being used and why they were created. Why did you feel it was important to take this approach?

Jessica Dimmock: We wanted to make a gun violence film where gun violence doesn’t happen. I think we’ve all seen so much of it, and it’s so hard to take, so we knew we wanted to make a film where no one actually gets hurt, and everything you see is a simulation. There is, of course, some skepticism on our part that any of these products are going to be the way that we actually get through this issue. But that being said, a lot of people that are making products and programs are trying to come up with a solution in the absence of real gun reform.

One of the people you interviewed, a self-defense trainer and ex-Green Beret who goes by the name Thrasher, says he doesn’t think guns are the root cause of our country’s mass shooting epidemic, and that “family structures [and] the lack of tribalism” are, instead, to blame. Was this the view of most of the people selling these safety products who you interviewed, or were their assessments more mixed?

Zackary Canepari: Yeah, I think for the most part. It’s interesting—I don’t know if they would have brought up guns if we didn’t ask. I think one thing that we tried to do in the film was point out that a lot of the trainers and people running the programs have police and military backgrounds, so they’re already coming from a place in which violence is much more present than what we experience as civilians.

JD: They’re bringing that kind of militarized approach into a non-military setting.

ZC: Thrasher’s response was kind of intense, but very much in line with what we heard, which is that mental health crises, family structure issues, things like that, are the reasons that this is happening with such frequency. And the only group that had a clear response were the kids. For the most part, the kids just understood what the problem was. They were the ones who were experiencing it. They’ve all grown up in this world where gun violence is the norm and lockdown drills are something they’ve always done. They’re the ones who say to the audience that guns are the number one killer of kids in this country. It’s not the adults that are saying that.

What else did you learn from the kids you spoke to for the film about how they cope with the threat of school shootings?

JD: I think what’s so tragic, and the thing that we’ve heard over and over again, is that they are thinking about it all the time—when they are in school and out of school. Obviously, shootings don’t just happen at schools; they happen at supermarkets and churches and nightclubs and all types of places. We would hear over and over again, kids are preparing. They’re sitting there thinking about what the safest exit would be when they’re in a confined space. When they’re in theaters, they think about where they could run away. It’s just a mental noise going on all the time, and that’s very tragic. And then when you also think about what else could and should be filling that brain space, it’s really awful.

In the mass casualty simulation you follow, volunteer students become actors who scream for help while wearing makeup to depict fake gunshot wounds. It’s hard to watch. What kind of rationale did officials provide for why they felt it was important to do these reenactments, given that leading groups of gun safety and education advocates, and psychologists, say that drills should not simulate actual events and that children should not routinely be part of them? Who or what did you get the sense they were for?

ZC: I think they’re mostly for two groups. One is actual first responders. I think the second group is the more important one, which is that it’s training civilians to be first responders. In the case of our film, that’s teachers. It’s really about getting adults prepared, mentally and even physically, for what to do in an active shooter event.

The people that are there fastest are going to be the civilians, and so in order to save lives, those civilians need to be prepared to run, hide, fight, and also stop the bleeding and barricade and all these different skills that are being taught across the country.

The kids are there because the belief system amongst most of the people in this space is that—and this is literally the slogan of one of the companies—’your body can’t go where your mind has never been.’ The idea is that if you drill and there’s not this level of intensity and blood and screaming, the drills won’t be effective. So the kids are there to give that extra push to the participants, and they’re there also because they’re part of these communities as well.

Did your own perceptions of the simulation change after watching them unfold?

JD: It took a while for it to dawn on us that everything that we were seeing is practice and not prevention, and I think that was kind of a mental switch for us. At a certain point, you realize that everything you’re seeing is about practicing what to do when it eventually happens, and that’s so defeatist, and yet, that’s where we’re at.

ZC: A crazy byproduct of this is that often these communities are united in these drills. They do feel empowered by them because they’ve done it together, and that makes a lot of sense. I think they could do a lot of other things together besides this, but this is the void that they’re trying to fill.

One of the most chilling parts of the documentary for me was the footage, during the simulation, of school shooters in Parkland, Florida and Nashville, Tennessee entering the schools where they ended up killing nearly two dozen people combined. Viewers may not even realize what they’re watching. Why did you integrate those clips in that way?

We’re talking about a very real American thing, and it’s probably the most shameful part of our national makeup.

JD: It’s meant to be subtle. You want the audience to remember that after all of this theater, this is a reference to the real thing. We really wanted to make sure we made a film in which no one ever gets hurt, in part because we want audiences to actually be able to sit down and watch it. And yet, at the end of the day, we’re talking about a very real American thing, and it’s probably the most shameful part of our national makeup.

Lawmakers don’t really feature much in the film at all, other than a few clips early on of some of them debating assault weapons bans. Can you talk about this choice?

JD: I think we just knew that if we approached this politically, there would automatically be this whole section of an audience that just wouldn’t watch it. They don’t want to be told what to think, they don’t want to hear from one type of politician or the other.

We didn’t want to preach to people. We felt like if we did that, we’d be probably preaching to the choir. I want parents to see this film. I want teachers to see this film. I want students to show this film to their parents. I don’t want to get in a red or blue, Democrat or Republican debate here.

ZC: It’s one of the reasons why the film is kind of built around the statistic about guns being the number one killer of kids in America. We didn’t need politics to argue over that.