Zohran Mamdani was elected mayor of New York on Tuesday, defeating former Democratic governor Andrew Cuomo for the second time in five months and capping a stunning rise from obscurity to the helm of the nation’s largest city. A 34-year state democratic socialist assemblyman from Queens, Mamdani became the city’s first ever Muslim mayor—and the first immigrant mayor in half a century—with an obsessive and inimitable focus on “affordability.” In the process, he ushered in a new era of city politics and slammed the door shut on an old one.

Mamdani’s platform, his ubiquity, his alliances and relationships, and his identity helped him build a new winning coalition.

The throughline of Mamdani’s campaign was a willingness to meet people where they were, in physical and ideological ways. For a democratic socialist, that meant trading dogma for a slate of unavoidable policies tied to unavoidable things: Free childcare, a rent freeze, fast and free buses, and city-owned grocery stores. His hopes and policy prescriptions were things that every voter deals with, or knew someone struggling with. The message was so unavoidable that Democrats everywhere else in the country kept going off-message to argue with it.

Mamdani was the most relentlessly disciplined Democratic nominee for anything that I’ve seen in years. He was conversant in the language of the city, and also its literal languages. (It was a good sign when Mamdani was falsely accused of using AI to film an ad in Spanish; it was a better sign when the candidate’s team promptly published an equally compelling set of outtakes.) You could accuse Mamdani of pandering, of course. But this is politics—the point is to pander in a way that makes voters feel seen and heard.

Heading into the primary, there was a common suspicion (shared by me) that for all of Cuomo’s weaknesses and Mamdani’s strengths, the coalition politics just weren’t there for a lefty challenger in New York City. But the returns then, and now, revealed a different story. Mamdani’s platform, his ubiquity, his alliances and relationships, and his identity helped him build a new winning coalition.

The DSA members in “the People’s Republic of Astoria” formed an organizing base that sustained him during the primary, but his campaign was equally at home in outer-borough neighborhoods like the two he featured in his launch video—working-class and home to large numbers of South Asian and Muslim communities whose residents had never been courted or seen to such a degree by a mayoral campaign. He won the primary convincingly, thanks in part to an alliance with the favorite son of North Brooklyn yuppies, the progressive Jewish comptroller Brad Lander. Mamdani’s coalition was historically young—this was the election where millennials finally seized control of the levers of power. But had crucial back-up from old-school leaders like US Rep. Jerry Nadler (who endorsed him immediately after the primary) and the Rev. Al Sharpton (who joined Mamdani at a rally in the final days).

Soccer fans were the Mamdani Coalition in a nutshell: a young, diverse, polyglot group that united immigrant communities and yuppies.

The videos and debate moments got all the attention, and the army of volunteers helped carry him across the finish line, but the nature of his coalition and of his unique style of campaigning was captured quite neatly, to my mind, by Mamdani’s attention to a subject candidates have traditionally ignored. A few weeks before the election, Mamdani held a soccer tournament on Coney Island with teams of varying skill sets from all over the city. Not long before that, he watched an Arsenal match with Spike Lee. He held a press conference to demand that FIFA make World Cup tickets available at a discount for New York City residents (again with the affordability), and reached out to a popular British soccer podcast to make the case to their listeners, too. No one has campaigned so thirstily for the votes of soccer fans in an American election, but soccer fans were the Mamdani Coalition in a nutshell: a young, diverse, polyglot group that united immigrant communities and yuppies.

This was a local race with national implications. I know that because national Democrats couldn’t stop offering unsolicited advice about what to do about Mamdani. The fact that the Democratic party’s brand tanked worse in New York City last year than basically anywhere else in the entire country is the type of thing that you might think would cause Democrats to perk up and take seriously a young and energetic challenger. Instead, a lot of powerful people whose job is to ostensibly think about the long-term health of the party argued that voters should rally behind a bully and a creep who helped tank the party’s brand in the first place.

But it’s instructive that while Sen. Chuck Schumer, the Senate minority leader from Park Slope, kept his distance, and Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, the House minority leader from Bed-Stuy, offered the most tepid of endorsements, Mamdani nonetheless did receive advice from another underdog candidate that Bill Clinton once tried to stop. President Barack Obama called to congratulate him after the primary, the New York Times reported, and spoke with Mamdani for half an hour on Saturday. Obama is better at politics than everyone else in his party, but also someone who knows from experience what it means to promise change in a party that doesn’t really want to. Sometimes, to build the future you want, you first have to shake free of the past.

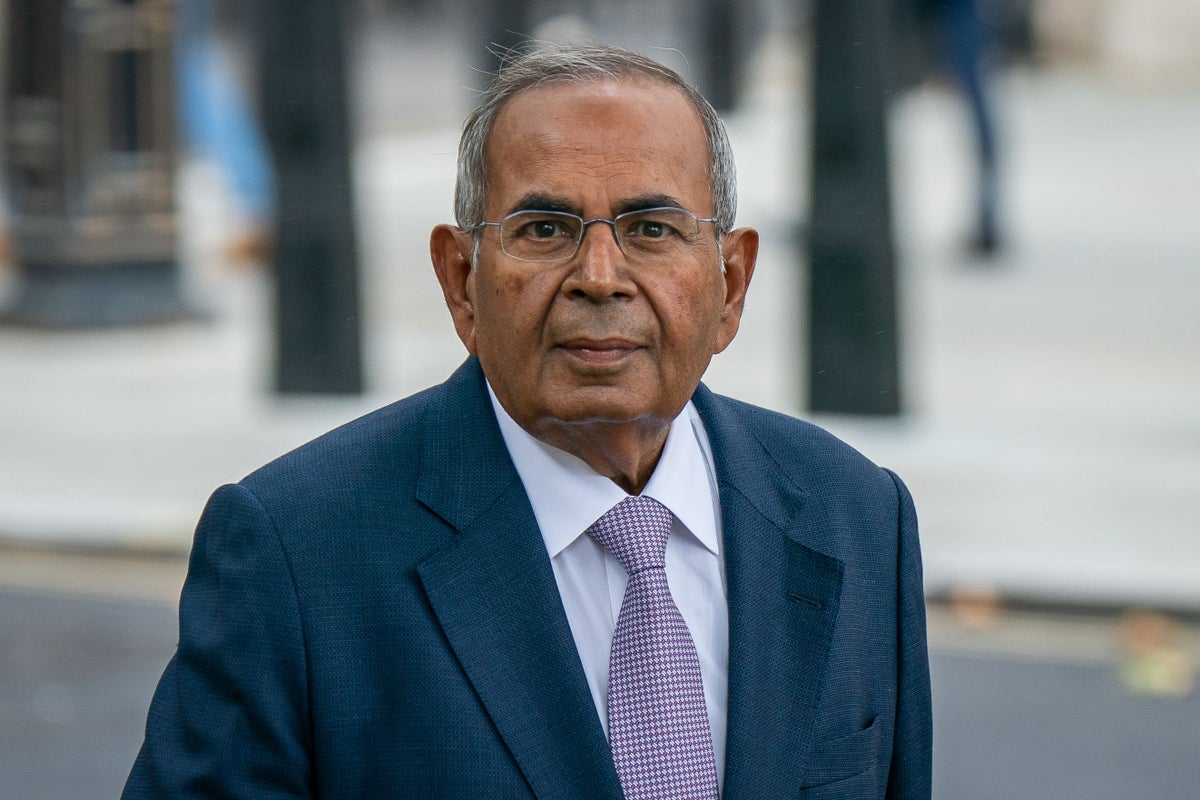

As much as the race was a validation of Mamdani’s efforts, though, it also marked perhaps the final chapter for the man he twice defeated. In the days and weeks after that June defeat, Cuomo allowed that he may have miscalculated. Borrowing from Mamdani’s color settings, if not his charm, he filmed a soft-focus video walking through a Manhattan park, and sought to portray himself as an amiable ex-gov who fixed up strangers’ cars. His face contorted into a mechanical smile. The theory behind Cuomo’s second campaign was that Republicans would join more conservative Democratic factions in uniting behind him, while he spoke more deliberately about affordability, and made the case for why he could succeed and Mamdani would fail.

I don’t know that someone as damaged as Cuomo could have truly seized a second chance, but the candidate barely even tried. Throughout the campaign, the man who resigned in disgrace after a state attorney general’s report found that he had sexually harassed nearly a dozen women insisted that his biggest regret was leaving office. (He continues to deny any wrongdoing.) Asked at a debate what he had learned from his first rejection at the polls, he said he regretted not being better at social media.

The man who resigned in disgrace after a state attorney general’s report found that he had sexually harassed nearly a dozen women was asked if he had any regrets. He said he regretted not being better at social media.

Aside from a call for more cops and the obvious quest for redemption, you’d be hard-pressed to say what Cuomo was running for office to do. His stickiest policy proposal was that Mamdani should not be allowed to live in a rent-stabilized Queens apartment anymore—a situation that Mamdani will soon resolve by moving into an 18th-century mansion in Manhattan. That fight was instructive, both in its weirdly personal nature and the ignorance of everyday life in New York City it displayed. Cuomo alleged that Mamdani was taking housing from “a poor person.” But only a very rich person would think that a poor person should be paying $2,300-a-month for a one-bedroom in Astoria.

It was in the home stretch where the former governor’s true colors really showed. Cuomo ran a grim, miserable campaign rooted in cynicism and fear. He laughed at the idea that his Muslim opponent might cheer on the 9/11 attacks. He suggested that the dual-citizen who emigrated as a child “doesn’t understand the New York culture, the New York values, what 9/11 meant.” His campaign released an AI-generated video featuring Mamdani eating with his hands and a Black man thanking the Democratic nominee for allowing him to commit crimes. His spokesman shared a comment from a pro-Trump influencer calling Mamdani a “terrorist.” His top surrogate in the final days—the disgraced sitting mayor—evoked the spectre of “Islamic exstremist” in Nigeria and said that a vote for Mamdani would turn the city into Europe. At a debate, Cuomo explicitly appealed to Sunni Muslims to reject a Shiite candidate whose views, he said, were “haram.”

In the final hours of the race, Cuomo even tacitly welcomed the endorsement of Trump himself (while also, with characteristic forthrightness, denying he was doing so) by asserting that the best way to avoid an authoritarian crackdown would be to vote for the candidate the authoritarian preferred. To the end, he never learned to say his opponent’s last name.

Mario Cuomo, the candidate’s father, famously said that you campaign in poetry but govern in prose. But that, as it happens, is a false choice. An epitaph can be both.