Walking along the flank of Medicine Mountain, I could see this wasn’t a typical hike in the Rockies. At over 9,500 feet in elevation, I was following a dirt track across a windswept ridgeline in the Bighorn Mountains of northern Wyoming. On the peak above, there was a bizarre spherical structure— an unmanned Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) radar station. Atop the bluffs in the hazy distance, I could just make out the wooden posts that encircled my enigmatic destination.

For years, I’ve been combing the nation, searching for clues of outdoor mysteries from the front-country to the backcountry. Thirty-five of the best stories about unexplained phenomena and baffling disappearances became the subject of my new book: Mysteries of the National Parks. Further enigmas can be found elsewhere on public lands, including within state parks, recreational areas, and more.

From a half-million symmetrical lakes to a lost gold mine, these are seven of the most intriguing outdoor mysteries that I’ve come across you can unravel on the ground, too.

Who Built the Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming?

After walking a mile and a half through the highlands of Bighorn National Forest, I reached a tundra clearing. Here, thousands of limestone rocks were long ago arranged into a ring-like structure. This is the Medicine Wheel National Historic Landmark, a United States Forest Service (USFS) site considered sacred by many Native American tribes. In this context, the term medicine essentially means spiritual. But what is the meaning and purpose behind the wheel’s design?

The Bighorn Medicine Wheel has a diameter of roughly 80 feet. Extending from a central rock cairn, there are 28 spokes, which seem to represent the number of days in a lunar month. Found around the perimeter ring, there are six additional cairns. One of these is set apart, at the end of the longest spoke, which seems to align with the summer solstice.

This is the southernmost example of several complex stone wheels found throughout the Rocky Mountains. Members of the Crow Tribe have said that when their ancestors migrated into the region 300-400 years ago, the Medicine Wheel was already here. As a result, its precise age, and who built it, remains a mystery.

How Long Will Nebraska’s Waterfalls Last?

Most outdoor travelers skip past Nebraska, but near the northern edge of the state, there’s a little-known oasis that reveals a conservation mystery. Hidden in a sunken valley beneath the rolling Great Plains, the Niobrara National Scenic River protects 76 miles of flowing stream where you can paddle past a shocking number of waterfalls. There are over 230 spring-fed falls, in fact, many of them tumbling into the river from the southside bluffs. There’s a unique reason for that. Despite being found in a particularly arid part of the High Plains and Sandhills, the Niobrara Valley cuts several hundred feet into the porous sandstones containing the Ogalala Aquifer.

Spreading beneath eight states, the Ogalala is the largest groundwater formation in the U.S., an underground reservoir feeding much more than the Niobrara’s falls. Over the past century, widespread pumping for agricultural and domestic purposes has gradually depleted the aquifer. Despite ongoing conservation efforts, each year more water is extracted than can be naturally replenished through rain and snow.

As a result, no one knows how long the Ogalala Aquifer—and the Niobrara’s waterfalls—might last. Should this vital water source run dry, it could trigger an environmental crisis to rival the 1930s Dust Bowl.

If you want to better grasp the situation, head to Smith Falls State Park, a popular paddling access and campground that’s home to Nebraska’s tallest waterfall at 63 feet. Here you can explore a river fed by an aquifer wrapped in a mystery, one that may or may not end in catastrophe.

Did Three Prisoners Survive an Escape from Alcatraz Island in 1962?

A few hours before midnight on June 11, 1962, three prisoners crawled through widened ventilation ducts, escaping from their cells at the U.S. Penitentiary on Alcatraz Island. Frank Morris and brothers John and Clarence Anglin were convicted bank robbers who’d been preparing six months for this moment.

Under the cover of darkness, they made their way to the shoreline where they inflated a makeshift raft stitched together from stolen raincoats. Wearing homemade life jackets, and using plywood paddles, the prisoners pushed off into the San Francisco Bay. According to a fourth accomplice who stayed behind, their intended destination was Angel Island, two miles away, from where they would continue to the mainland. In a clever twist, they’d left behind dummy heads tucked into their bunks, which would give them a nine-hour head start before first count.

The dramatic escape triggered one of the largest manhunts in U.S. history, leading to widespread media coverage and a famous 1979 film starring Clint Eastwood. Though no bodies were ever found, the official investigation determined the trio had likely drowned in the frigid waters. But a series of clues would emerge suggesting the escapees may have survived.

Several days after the escape, some items were found floating near Angel Island, including a prisoner’s wallet, pieces of rubber, and a homemade paddle. One of their life jackets was found floating near Alcatraz, while another washed up on the Marin Headlands, outside the Golden Gate. But were these items scattered during a drowning or abandoned after a successful escape? Alleged sightings of the men would continue for decades. Eventually, even the escapees’ family would claim they’d been discreetly in contact over the years.

The infamous prison closed in 1963, but the mystery would linger long after Alcatraz became a national park site. Today, you can take a ferry from San Francisco to explore the island prison. Other ferries lead to Angel Island State Park, which has many hiking routes. Several trails converge at the summit of Mt. Livermore, offering excellent views of Alcatraz and the watery expanse the prisoners attempted to cross.

How Were a Half-Million Symmetrical Lakes Formed on the East Coast?

Stretching across the densely populated East Coast, from Northern Florida to Southern New Jersey, a half-million mysterious lake beds lie hidden in plain sight. For centuries, these so-called Carolina bays have baffled the occasional observer who noticed their unusually round profiles. But it wasn’t until the rise of aerial photography, in the early 20th century, when it became clear how strange they truly are.

Thousands of elliptical depressions pockmarked the sandy coastal plain. In black and white photos of the 1930s, the bays looked like craters on the moon. Some were bigger, some smaller. A few overlapped each other. Most were seasonally dry and filled with swampy vegetation. Many had been plowed for agriculture. Others, particularly in North Carolina, remained year-round lakes encircled by sandy rims. The most bizarre feature? Each was pointing roughly in the same direction, with their long axes running from northwest to southeast.

Today, the origin of the Carolina bays remains a geologic mystery. The prevailing theory is that, during prehistoric ice ages, changes in sea level and fierce winds created large sand dunes. Gradually, the elliptical lakes formed from prevailing winds and currents within the flattening dunes. An exciting alternative posits that the bays formed from a comet or meteor impact, but that scenario seems less likely, especially since other wind-oriented lakes have been found around the globe.

Some of the most intact Carolina bays are in Bladen County, North Carolina, including at Jones Lake State Park. Established during the era of Jim Crow segregation, the park was designated for African Americans only. As a result of racist underfunding and limited development, two mysterious bays were ironically preserved. And, today, you can hike or paddle through this semi-wilderness.

What Was the Original Route of the Old Spanish Trail Across the Southwest?

If you’ve ever road-tripped around the famous red-rock canyons of the American Southwest, perhaps you’ve seen scattered markers for the Old Spanish Trail. In use for several decades during the mid-1800s, this oft-forgotten and formidable trade route is quite different from other overland traces, such as the Oregon and California Trails, which were thoroughly documented.

Despite being an east-to-west route, the rugged iterations of the Old Spanish Trail careen hundreds of miles to the north and south. Plus, nobody knows exactly where it went. The reason is its enigmatic origin story. During the early 19th century, there were two Spanish-settled colonies on Mexico’s northern frontier. One was in Northern New Mexico, the other in Southern California. In between was an inhospitable and mostly unmapped desert.

In November 1829, a relatively unknown trader named Antonio Armijo led a sixty-person pack train west from Abiquiu, New Mexico. For three months, the party scouted out a path across the desert, frequently detouring around impassable canyons and mountains.

When Armijo’s caravan arrived at Mission San Gabriel, near present-day Los Angeles, the inhabitants were surprised to see the party arrive from an unexpected direction. The traders exchanged woven textiles for mules and returned home in just two months, setting the stage for overland migration across the Southwest. Before vanishing from the historical record, Armijo submitted a confoundingly short report to the New Mexico governor. Basically, it’s just a daily list of campsites and water sources with no distances between.

Historians have long puzzled over Armijo’s journal, trying to decipher the particulars of his route. But it seems likely he passed near present-day highlights such as Monument Valley, southern Lake Powell, Zion National Park, and Lake Mead. So, next time you’re road-tripping through the labyrinths of canyon country, and you lose track of where you’re at, it’s no mystery why. It’s always been that way.

Is There a Lost Gold Mine in the Guadalupe Mountains of Texas?

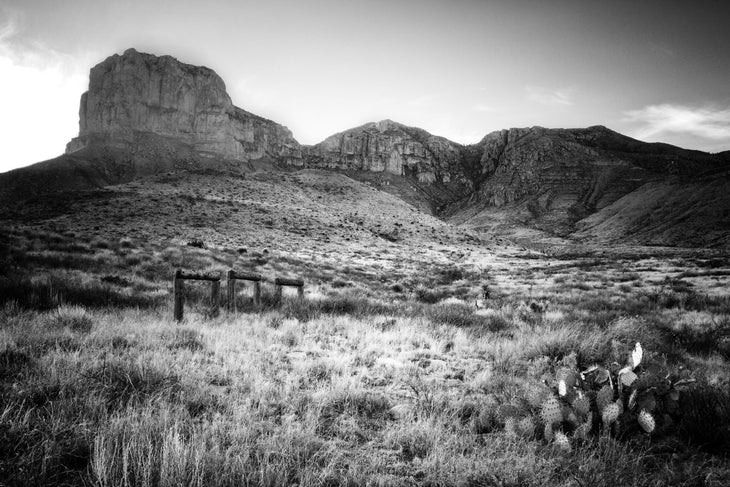

The West is filled with legends about hidden treasures and lost gold mines. Some tales may be real, while most were probably invented, but both can lead you to new adventures. One example is the lost Sublett gold mine, said to be in the vicinity of Guadalupe Mountains National Park in far west Texas.

As the story goes, Ben Sublett was an itinerant frontiersman who worked for a westward-expanding railroad in the early 1880s, somewhere out in Apache country.He supposedly stumbled across an abandoned Indian or Spanish mine. Sublett would periodically disappear for a few days or longer and return to town flush with gold nuggets. His secret mine was said to be somewhere west of the Pecos River, perhaps in the Guadalupe Mountains or Rustler Hills. Despite repeated attempts to track him to the source, the mine was never found, and Sublett took its location to his grave.

Lost mines are fun, but is there any truth here? The Guadalupe Mountains are an impressive range, rising abruptly over 3,000 feet from the desert floor. Challenging trails lead up to park highpoints like El Capitan and Guadalupe Peak, the tallest summit in Texas at 8,749 feet. Seeing limited visitors, the quiet park sure feels like a place to stumble across a hidden treasure, except for one thing.

The Guadalupe Mountains are the petrified remnants of an ancient reef. Its limestone formations yield plenty of fossils but no gold deposits. However, natural caves have been found in these mountains, including those at nearby Carlsbad Caverns National Park. One version of the Sublett legend suggests he was actually visiting a hidden cache of gold relocated from somewhere else. At the very least, this mystery remains possible, making for the perfect trail talk while exploring an unexpected place.

What’s the Story Behind Florida’s Spite Highway?

After World War II, South Florida was booming. Hotels and homes stretched from Miami and down the sparkling Overseas Highway to the tip of Key West. During the 1950s and 60s, real estate developers went looking for new areas to build.

Between the city and Key Largo was one of the region’s last remaining sections of wild Atlantic coastline. So, plans were proposed to turn Biscayne Bay into another Miami Beach. A coral reef would be cut out for a deepwater port. Nearby would rise an oil refinery and powerplant. New causeways would connect mansions and resorts. In preparation, about a dozen landowners incorporated the so-called city of Islandia to develop the northernmost Elliot Key and surrounding islands.

By now, South Floridians were growing weary of the sprawl, and gradually a movement spread to protect Biscayne Bay as a national park. By 1968, designation seemed imminent in Washington D.C. Then the jilted city council of Islandia sent a wrecking crew to Elliot Key, where they illegally bulldozed the subtropical forest, creating a six-lane roadway down the centerline of the seven-mile island. Park opponents hoped the destruction might deter the conservationists. Instead, the supporters prevailed, and the forest re-grew. Islandia was sued and eventually disbanded.

Today, Biscayne Bay National Park uniquely preserves more warm waters than land, being best known for snorkeling and boating. But running down the middle of Elliot Key is the park’s only hiking route, that passes through an enigmatic tree tunnel with a disturbing backstory.

There always have been, and always will be, threats to public lands from competing interests and greedy developers. The Spite Highway Trail is a reminder of a pressing mystery, one that’s particularly relevant in our current moment: will wild places like the national parks survive?

For more outdoor mysteries that you can explore, check out Mike Bezemek’s new book: Mysteries of the National Parks: 35 Stories of Baffling Disappearances, Unexplained Phenomena, and More.

The post The Most Baffling Mysteries and Unexplained Phenomena in America’s Great Outdoors appeared first on Outside Online.