This article is a collaboration with Autonomy News, a worker-owned publication covering reproductive rights and justice. Sign up for a free or paid subscription, and follow them on Instagram, TikTok, and Bluesky.

Crisis pregnancy centers have played a central role in the anti-abortion movement since the 1960s, often misleading and confusing people seeking abortions while purporting to help them. They mimic the appearance of abortion clinics, with similar-sounding names and even lookalike logos. Their volunteers sometimes pose as clinic staff to divert abortion patients from getting care. Their websites are teeming with disinformation, including claims that abortion is unsafe or linked to future mental illness, breast cancer, and fertility issues. “A killer, who in this case is the girl who wants to kill her baby, has no right to information that will help her kill her baby,” Robert Pearson, founder of the very first CPC in the US, once declared.

Abortion rights advocates have long called on lawmakers to rein in CPCs and their misleading practices. But a 2018 Supreme Court decision struck down a California consumer-disclosure law’s attempt to do just that, making it virtually impossible for states to enact regulations that single out CPCs.

Soon after, pro–abortion rights legal scholars suggested a new approach: to go after pregnancy centers for false advertising. This regulatory strategy seemed like it would be a slam dunk, particularly thanks to a CPC practice that has rapidly become crucial to the anti-abortion movement’s strategy: abortion pill “reversal,” an unproven medical protocol that CPCs claim can halt a medication abortion about two-thirds of the time.

The medical consensus on APR is clear: It’s not possible to “reverse” the effects of the abortion drug mifepristone, and attempting to do so may even be dangerous. To blue-state legislators and attorneys general, the legal issue was also straightforward: Making false promises—especially when those claims could hurt people—is illegal under a host of state and federal laws that ban misleading and deceptive advertising practices.

But three years after the reversal of Roe v. Wade, efforts to regulate CPCs for false advertising appear poised to backfire spectacularly. In fact, by pursuing pregnancy centers based on their promotion of APR, well-intentioned Democrats may have unwittingly set the stage for the anti-abortion movement’s next great Supreme Court victory.

In its term beginning this month, the high court will hear a case stemming from New Jersey’s attempt to subpoena information—including scientific evidence to back up claims about APR—from First Choice Women’s Resource Centers, a CPC chain with five locations throughout the state. In a brief, First Choice compares the subpoena to Southern states’ attempts to force the NAACP to produce member lists in the late 1950s and early ’60s. Technically, the case has nothing to do with APR or other questionable CPC practices. It’s about a specific legal fine point: Can CPCs run straight to federal court to fight an attorney general’s subpoena, as First Choice did, or must they first sue in state court?

The fear is that, if far-right legal activists succeed, states could ultimately be barred from intervening in any way when CPCs advertise unproven medical treatments like APR.

Boring as this procedural quibble may seem, a favorable decision would be a significant win for CPCs. They have a much better shot at winning any case in the Trumpified federal courts than they do in state courts that may be more supportive of abortion rights. What’s more, the ability to use friendly federal courts as a shield from state regulation would set pregnancy centers up for success in other lawsuits making their way to the Supreme Court—ones that could eliminate states’ ability to crack down on APR and other questionable practices entirely.

Three cases are waiting in the wings. This summer, a Trump-appointed federal judge permanently blocked Colorado from enforcing a 2023 ban on APR against two plaintiffs who sued to block it: a CPC and a nurse practitioner. The first-of-its-kind statute labeled APR a deceptive trade practice. Meanwhile, in New York and California, federal court battles are raging between state attorneys general and CPCs, this time over state claims that merely advertising abortion pill “reversal” is fraudulent and misleading.

The fear is that, if far-right legal activists succeed, states could ultimately be barred from intervening in any way when CPCs advertise unproven medical treatments like APR. That could grant CPCs an unfettered right to spread medical disinformation—no matter how much it may harm vulnerable people navigating an already deadly post-Dobbs landscape.

In all of these cases, CPCs are represented by the far-right legal juggernaut Alliance Defending Freedom, which wrote the Mississippi abortion ban the court used to overturn Roe and has played a leading role in major anti-abortion and anti-LGBTQ litigation in recent years. This includes NIFLA v. Becerra, the 2018 case in which the Supreme Court struck down a California law that required unlicensed CPCs to disclose their lack of licensure, and licensed pregnancy centers to provide information about family planning services.

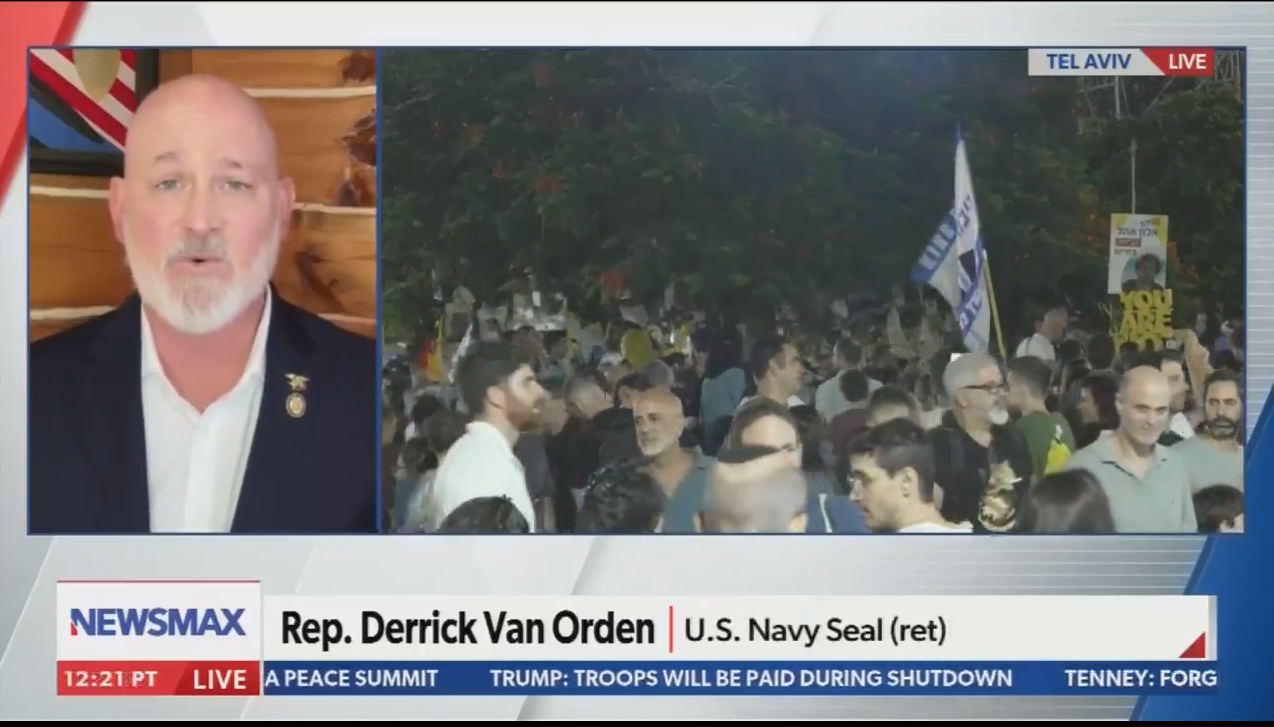

Recordings from a March CPC industry conference—made by an attendee and shared exclusively with Autonomy News—confirm that ADF and allied law firms view abortion pill “reversal” as a linchpin in their strategy to expand legal and religious protections for the centers.

The conference was hosted by the National Institute of Family and Life Advocates, an advocacy organization that provides legal counsel, education, and training for more than 1,800 member CPCs across the US; it was also the lead plaintiff in NIFLA v. Becerra. ADF senior counsel Kevin Theriot joked that NIFLA “seems to be our primary client these days,” and suggested that another legal victory is imminent.

Peter Breen, head of litigation at the Thomas More Society—another right-wing law firm that works closely with the anti-abortion movement—told the audience that the goal is to win court decisions that “protect you a little more vigorously, maybe, than you’re being protected right now.”

In all of these cases, ADF asserts that by attempting to regulate CPCs, blue states are “chilling” their First Amendment rights.

But conference recordings also reveal that, behind closed doors, many anti-abortion doctors are reluctant to embrace APR, despite its ubiquity in their movement. The recordings feature rare admissions about the challenges and risks associated with the experimental treatment, including mention of side effects not included in official case reports. These comments raise questions about how, exactly, CPCs plan to capitalize on any newly won freedoms, and whether anti-abortion leaders will plow ahead with APR when even their own medical experts are hesitant.

The FDA–approved protocol for medication abortion involves two drugs: mifepristone, which blocks progesterone, a hormone essential for pregnancy; and misoprostol, which causes the uterus to contract and expel the pregnancy tissue. In abortion pill “reversal,” patients who have taken mifepristone but haven’t yet taken misoprostol are prescribed progesterone under the theory that the hormone will reverse the effects of mifepristone and “save” the pregnancy.

This theory was inspired by the longstanding use of progesterone to prevent miscarriage in early stages of pregnancy—even though randomized controlled trials have found that progesterone therapy has little benefit for most miscarrying patients. The man behind the hypothesis is Dr. George Delgado, a family medicine doctor and prominent conservative activist based in the San Diego area.

As is often the case in disinformation campaigns, there is a kernel of truth to the anti-abortion movement’s claim that pregnancy can continue after taking mifepristone. But APR has nothing to do with it.

Delgado founded the Steno Institute, an anti-abortion research organization that counts San Francisco archbishop Salvatore Cordileone among its advisers. He sits on the board of the American Association of Pro-Life OBGYNs and is the medical director for a CPC called Culture of Life Family Services. Most recently, he was a plaintiff in Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. FDA, in which anti-abortion medical groups unsuccessfully challenged the FDA’s 25-year-old approval of mifepristone, plus more recent regulatory changes that have vastly expanded access to the drug. ADF represented Delgado and the other doctors in the case.

Delgado published the first report on APR in 2012—a case study with just six patients, finding that four of them carried their pregnancies to term. (Case reports are considered among the weakest forms of scientific evidence, per a widely used ranking system.) In 2018, Delgado published a larger case report in the journal Issues in Law & Medicine, which has direct ties to AAPLOG. Of 754 patients initially given progesterone, 547 remained in the study and 257 later gave birth, Delgado claimed.

As is often the case in disinformation campaigns, there is a kernel of truth to the anti-abortion movement’s claim that pregnancy can continue after taking mifepristone. But APR has nothing to do with it. “We know that mifepristone, by itself, is not a very effective abortion-inducing medication,” says Daniel Grossman, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, San Francisco who is the director of Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health and the lead author on a 2015 systematic review of the evidence on APR. In one early French trial of mifepristone, for example, 23 percent of participants who took the now-standard dose of mifepristone alone remained pregnant. Supposed APR “success stories” may simply reflect the fact that mifepristone doesn’t work well on its own—this is precisely why it’s used in combination with misoprostol.

In Grossman’s view, the anti-abortion movement’s promotion of APR is akin to an “unmonitored research project.” In the US, he adds, there is a “very ugly history of experimenting on people from marginalized groups”—and people who have abortions disproportionately belong to such communities.

In Grossman’s view, the anti-abortion movement’s promotion of APR is akin to an “unmonitored research project.”

Still, after Delgado’s purported discovery, anti-abortion legislators moved quickly, eventually passing laws in more than a dozen states that required abortion providers to inform their patients of the possibility of “reversing” their medication abortions. (Many of those states now ban abortion entirely.) Delgado went on to found the Abortion Pill Rescue Network, a progesterone-prescription hotline that’s now run by the CPC organization Heartbeat International.

In public, anti-abortion groups boast about hordes of women who they claim have changed their minds and successfully “reversed” their medication abortions. In June, Heartbeat International announced that the Abortion Pill Rescue Network has saved “more than 7,000 lives”—up from the “6,000 lives and counting” it claimed in November 2024. It’s impossible to know whether or not these statistics are true. CPCs have a history of inflating the number of clients they serve and the value of services they provide. Creating a perception that demand for “reversal” is exploding reinforces the longstanding myth that many people are unsure of their decision to have an abortion. It’s also a conservative answer to the increasing popularity of medication abortion, which accounted for nearly two-thirds of all abortions in the US in 2023—double the rate from 2014.

But at the NIFLA conference, several prominent anti-abortion physicians seemed ambivalent about APR, even as CPC leaders projected bravado about the legal cases and dismissed potential safety concerns.

Based on back-and-forth during two sessions—a medical roundtable and a legal Q&A—it appears that many CPCs aren’t even providing APR on site and are instead referring patients to the Heartbeat hotline. This is ironic considering the anti-abortion movement’s strident opposition to telehealth for abortion pills. But it tracks with the results of a recent study, which found that only 3.8 percent of CPCs were advertising on-site progesterone prescriptions in 2024.

During the medical roundtable, Virginia-based family physician and Heartbeat hotline provider Karen Poehailos claimed that demand for APR “has been going through the roof.” A decade ago, she’d get five requests per year, she said; in the three months before the conference, she said she’d written “13 or 14” prescriptions. (Given that there were roughly 643,000 medication abortions in the US in 2023, three to five attempted reversals per month is hardly a huge number.) Poehailos acknowledged that growth in abortion pill use may help explain the rise in APR requests. ”Women can get these as easily as clicking online,” she said. “They did not have to think about as much before they started the abortion.”

In addition to serving as NIFLA’s assistant medical director, Poehailos is also a telehealth provider for FEMM, a fertility tracking app whose development was funded by an anti-abortion billionaire. She estimated that in the past decade, only about three of her APR patients were local, meaning she was able to see them in person. “The rest of them have been through telemedicine,” she said, which requires her to be extra careful. “When these women are so far from me…I document like crazy, and I pray that God protects me,” she said. It also helps to have “friends at ADF,” Poehailos said, apparently referring to Alliance Defending Freedom.

“The majority of the women I have worked with, even if [APR] is successful, will have some bleeding…“If you see a subchorionic [hemorrhage], that’s kind of expected. You pray it’s not a huge one.”

One of the challenges of APR, Poehailos said, is dealing with a common side effect, bleeding. “The majority of the women I have worked with, even if [APR] is successful, will have some bleeding,” she noted—specifically subchorionic hematoma or hemorrhage, a relatively common condition in which blood collects between the uterine wall and the outside of the gestational sac. Usually the bleeding is mild and resolves on its own. But this outcome isn’t reported in the papers that anti-abortion physicians have published on APR, Grossman points out. “If you see a subchorionic, that’s kind of expected. You pray it’s not a huge one,” Poehailos added.

During their discussion, Poehailos and two other doctors also lamented the quality of some of the medical testing at CPCs they’ve worked with, including ultrasounds and even basic urine pregnancy tests. “We want to serve these women well, we want to serve them in the heart of Jesus,” Poehailos said, “but we are providing medical services under someone’s license, so please … I’m sorry, but I’m not sorry. You need to be serving these women better than this.” Neither NIFLA nor Poehailos responded to requests for comment.

Part of the problem may be that CPCs appear to be having trouble attracting specialized professionals. At one point, Sandy Christiansen, medical director for Care Net, another CPC umbrella organization, reassured the crowd that they needn’t find an OB-GYN to be their medical director. Any type of doctor, even a pathologist or orthopedic surgeon, could do the job, she said. “All doctors get trained in women’s medicine to some extent…they can read a scan,” she said. Christiansen didn’t respond to a request for comment.

But ultrasound training has only recently become common in US medical schools, and obstetric ultrasound is even more specialized. Indeed, one audience member, who identified herself as a registered diagnostic medical sonographer, said her center’s medical director was a psychiatrist. As a result, “she puts a lot of trust into us.”

Poehailos acknowledged that some physicians refuse to provide APR themselves. “Some centers, their doctors are not comfortable prescribing, and they just want to be able to provide ultrasounds for doctors who do,” she said.

During the legal Q&A, some audience members expressed concern about potential repercussions associated with advertising or offering APR. But lawyers on the panel didn’t seem worried.

“I think everyone should go get a [t-]shirt that says ‘It’s just progesterone,’” said NIFLA attorney Angie Thomas, to laughter from the audience.

Based on the discussion, the claim that state laws are “chilling” CPCs’ speech appears grounded more in legal strategy than in reality. In California, for example, Attorney General Rob Bonta sued Heartbeat International and a CPC chain called RealOptions Obria over their claims about APR. In a related case, ADF is representing NIFLA and another CPC—neither of which Bonta sued—arguing that the attorney general’s actions chill these organizations’ First Amendment rights. As a result, NIFLA’s “official recommendation” to pregnancy centers in California is not to offer APR, said Anne O’Connor, the organization’s vice president of legal affairs—not because CPCs’ rights really are being “chilled,” but because claiming so strengthens their ongoing case against Bonta. “ADF recommended, you know, it’s better to go conservative in that, to allege that our First Amendment rights have been chilled by what the AG is doing,” O’Connor said.

“So you would suggest not telling clients about [APR]?” asked an audience member who said she was affiliated with a CPC in California.

“I told you that’s the official,” said O’Connor. The audience laughed, seeming to pick up on a hint.

Other lawyers also seemed to admit that CPCs are free to make APR referrals at the same time they claim they’re being censored.

ADF’s Theriot said CPCs could keep giving out information about abortion pill “reversal” and making referrals. “There’s a difference between advertising it,” he said, “and giving people information about the possible availability.”

“I think most of the centers in California are still doing it,” added Breen of Thomas More Society, which is representing Heartbeat against Bonta, suggesting that Bonta’s suit has not actually changed CPCs’ behavior.

Breen did not respond to a request for comment. In an emailed statement, Theriot said ADF “will fearlessly stand alongside pregnancy centers in their ministry to support pregnant women and their unborn babies” and in their legal fights against “ideologically and politically driven attorneys general.” “We remain confident that our clients’ First Amendment rights will be protected—even if that means taking these cases all the way to the US Supreme Court.”

While CPCs have been part of the anti-abortion movement for decades, their numbers have skyrocketed in the past 15 years as Republicans have consolidated their power and waged all-out war on reproductive rights. By June 2022, when Roe v. Wade fell, CPCs outnumbered abortion clinics by as many as 15 to 1 in some states. And since Dobbs, CPCs have received cash injections from state governments and private philanthropists alike, now raking in nearly $1.5 billion a year.

But as the industry has grown, criticism has intensified. Abortion rights advocates have worked hard to inform the public about CPCs’ deceptive practices, branding them as “fake clinics”—a label that’s stuck. Encouraged by organizations like NIFLA and Heartbeat, CPCs have responded by trying to become more “medicalized”—bringing in more licensed staff and offering more medical services, such as testing, and less commonly, treatment for sexually transmitted infections. In addition to conferring an aura of legitimacy, medicalization has the potential to open up new funding streams. For example, RealOptions Obria Medical Clinics—one of the chains Bonta sued—operates licensed facilities that accept the state’s version of Medicaid.

Abortion rights advocates have worked hard to inform the public about CPCs’ deceptive practices, branding them as “fake clinics”—a label that’s stuck. CPCs have responded by trying to become more “medicalized.”

Reproductive health experts generally see abortion pill “reversal” as part of this medicalization trend. APR also gives the anti-abortion movement another way—besides lawsuits and legislation—to fight back against the soaring popularity of abortion pills in the post-Roe era. While growing numbers of patients have turned to telehealth providers for abortion care, some three-quarters of abortions—including many via pills—still involve at least one in-person visit to a clinic. And many of those patients are encountering CPC volunteers who try to convince them to “reverse” their abortions by taking progesterone instead of misoprostol.

At least one abortion provider in the South says she has begun to hear from patients who’ve been drawn in by APR after appointments at her clinics. Calla Hales is the executive director of A Preferred Women’s Health Center, which operates four clinics across North Carolina and Georgia. While APR is more than a decade old, in Hales’ experience, the phenomenon of patients getting ensnared by it is relatively new.

“I would have never been able to point to a single anecdote prior to Dobbs,” she says. But this year alone, patients have called her clinics at least six or seven times in as many months after someone affiliated with a CPC convinced them not to take their misoprostol. Some patients then called Hales’ clinic back wanting to “reverse” their “reversal,” a situation in which there is no medical protocol, so health-care providers are flying blind.

In one case, Hales says, a patient traveled to one of her clinics from a state with a total abortion ban. After they returned home, family members took them to a CPC, which tried to convince them to “reverse” the medication abortion they had already started. In the other instances, patients were approached by CPC volunteers standing outside one of Hales’ clinics. A patient who is duped by the “reversal” sham, Hales adds, is likely to have to travel out of their home state again to complete their abortion—or be forced to seek follow-up care at an emergency department, where doctors may be hostile, lack adequate abortion training or both. “It’s really heartbreaking,” she says, “because there’s so much misinformation as it stands, and it’s really hard for patients to navigate getting abortion care in the first place.”