It was supposed to be our short day. Just four miles downstream would take us from Kolb Camp, a scenic cliff-side beach in western Colorado, to Rippling Brook, our next campsite. To our surprise—our backs aching, hands torn, and noses sunburned—the day would be spent unpinning a very stuck 12-foot raft in a precarious, potentially deadly rapid.

I thought I was prepared for this trip, having completed three multi-week rafting adventures down the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, totaling more than 70 days collectively. But this was my first trip down its sister river, the Green. We targeted the famed Gates of Lodore, a 43-mile whitewater stretch on the Green River, that carves through dramatic canyon walls and is surrounded by mountains soaring skyward to 9,000 feet in elevation. It spans Dinosaur National Monument, beginning in Colorado and ending in Utah.

In August, I spent five nights on this section with 19 other boaters—and we spent too many hours unpinning boats. Despite the carnage, I found this stretch of the Gates of Lodore to be a perfect adventure for would-be canyon boaters.

New to Canyon Boating? Gates of Lodore is a Perfect Entry

If you’re intimidated by the long, multi-week aspect of a Grand Canyon rafting trip, and the extremes that a desert river trip entails, the Gates of Lodore is a perfect introduction to whitewater. Whereas a private Grand Canyon rafting trip encompasses 277 miles, spanning up to 26 days, the Gates of Lodore is comparatively short. Completing the full stretch takes anywhere from three to five days.

Because of its fame, obtaining a permit for the Grand Canyon is highly competitive. And on a Grand Canyon trip, challenging rapids can be found throughout most of the river stretch. High points on the Grand Canyon can span up to 8,000 feet in elevation—much higher than the tallest peaks in the Gates of Lodore. Access points for emergency bail-outs can be much more difficult in a deeper canyon.

Boaters are less likely to encounter these hurdles in the Gates of Lodore.

“Gates of Lodore is a fantastic stretch to do with a large group because all the difficult rapids are in the first ten or so miles, and then you have stunning scenery with easier water for the rest of your trip. Three pinned rafts in five miles is a great icebreaker for 20 mostly strangers,” Greg Doctor, our trip leader, told Outside.

Doctor said that despite our group’s setbacks and accidents, the only major disagreement our party had was what music to play.

“It was sort of a dream trip in that we had crystal clear water with fun rapids backed by giant desert sandstone walls, all with perfect weather,” he added.

While Indigenous groups have lived in the region for thousands of years, the river was largely introduced to the Western world when geographer John Wesley Powell ran his famed descent in 1869, shortly before becoming the first person to document rowing the Grand Canyon. A member of Powell’s group named the Gates of Lodore after the English poem, “The Cataract of Lodore,” originally written by Robert Southey in 1820. It reads:

And so never ending, but always descending

Sounds and motions for ever and ever are blending

All at once and all o’er, with a mighty uproar

And this way the water comes down at Lodore

“Pin It to Win It” Quickly Became Our River Crew’s Motto

Although Gates of Lodore is a perfect introduction to canyon boating, this section is also rowdy and fun for experienced boaters. This became apparent after our group popped the floor of one of our rafts, which later resulted in multiple pins.

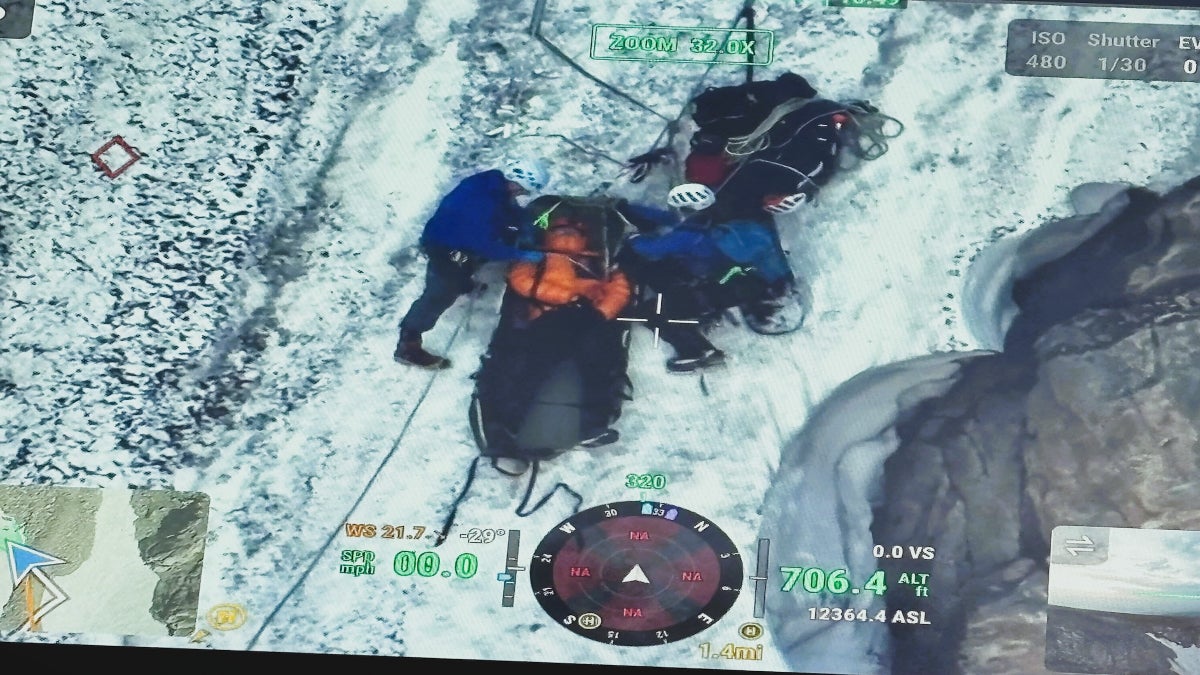

A “pin” happens when a raft gets physically trapped against an obstacle in the river, commonly a rock. Because the current is pushing directly against the boat, often thousands of cubic feet per second, the immense pressure makes it incredibly difficult to continue downstream.

How do you unpin a raft? The rescue system, often referred to as a pin kit or z-drag, is a complex arrangement of pulleys and lines that provides humans with a mechanical advantage against the force of the river.

During our five days boating through the Gates of Lodore, we encountered two major pinning locations: the Birth Canal at Triplet Falls, as well as Huggy Bear Rock at Hell’s Half Mile.

Rapids are based on a class system, with Class V being the hardest and most hazardous, often characterized by the most technical features. Rated a Class III, Triplet Falls is about 12 miles downstream of the put-in, and has been the site of numerous fatalities throughout the years. The rapid is surrounded by canyon walls rising 1,200 feet or more above the river and features an undercut wall that can easily trap a body.

So-named for the three large boulders that make the dangerous feature, Triplet Falls is one of the most technical rapids on this section. During a low water trip like ours, the rapid is a bony rock garden that could easily bump a raft off its line. After navigating it, boaters must face the Birth Canal, a narrow slot between two large, undercut boulders. All hands on deck and five hours later, we successfully got the raft unpinned.

Mikey Wrobel, a Colorado-based Class IV+ guide with seven years of experience, said his boat was pinned in large part because the raft’s floor popped on the first day. With little buoyancy and a heavier-than-usual load, moving dynamically through the current was difficult.

“I just kept telling myself that it’s not if I pin, but a matter of when—and that day was my day. Three pins and a popped floor on the first day, I feel like most people would throw in the towel,” Wrobel told Outside.

“The pin at Triplet Falls was mentally and physically straining, but everyone on this trip was amazing, and everything turned out okay,” he added.

Our second mishap happened at Hell’s Half Mile, a Class IV rapid close to a quarter-mile long. Large boulders clog the entrance of the rapid with a mid-stream rock named “Lucifer,” notorious for pinning boats. Our wrap actually occurred at a much less devious-sounding feature—Huggy Bear. It’s at the bottom of the rapid, right where you think you’re in the clear, and greeted one of our boats with open arms. This unpin took about an hour or so, and we were able to run the rest of the rapid—and the river—unscathed.

We pinned, we partied, and we truly embraced all that this unique landscape had to offer.

A Duality of Intimacy and Isolation

The success of a trip depends on the capability of your team. Over the course of our multiple pins, our crew bonded and battled its way through the canyon.

We also made sure we adhered to the basic advice for running rivers. Make sure you’re equipped with the right gear and prepared to handle disaster should it strike. In rapids, always wear your personal floatation device (PFD) and helmet. Know how to use your gear, especially if you carry a throwbag, and practice humility. Rapids are potentially life-threatening situations and should be taken seriously.

“Find mentors, take a swiftwater rescue course, and never forget that humans cannot breathe underwater. Be humble—river running is for fun; it is not a bicep measuring contest,” said Doctor, who is also an emergency physician with special interests in wilderness medicine and drowning resuscitation.

Both intimate and isolating, a multi-day river trip allows for a deeper connection to the surrounding environment while offering near-complete isolation from the external world. This dynamic of connectedness and disconnectedness on the river has stood the test of time.

During his journey down the Green River, Powell described the special light unique to a canyon, writing that “at noon the sun shines in splendor on vermilion walls… and the canyon opens, like a beautiful portal, to a region of glory.”

“This evening, as I write, the sun is going down and the shadows are settling in the canyon… and now it is a dark portal to a region of gloom, the gateway through which we are to enter on our voyage of exploration tomorrow, what shall we find?” he continued.

That intrigue and mysteriousness still rest in the canyon walls today. As any boater can attest, a river trip is one of those truly primitive experiences where one can completely disconnect from the world and enjoy the presence of those around in a largely inaccessible, yet breathtaking, landscape. For some, it’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. For others, it’s a way of life. It’s up to you to choose.

The post Can’t Commit to a Month Rafting the Grand Canyon? Meet Its Sister River. appeared first on Outside Online.