This story was produced by the independent, nonprofit newsroom Canary Media and co-published by Mother Jones.

Gary Yerman, 75, sat nervously in a noisy ballroom in Virginia Beach, Virginia, counting down the minutes until he could shed his ill-fitting double-breasted suit for a sun shirt and blue jeans. He introduced himself as a fisherman of 50 years to a stranger seated next to him at the banquet table.

“That sounds really hard,” the other man replied.

“Not as hard as it’s going to be to go accept this award and talk to a room full of people,” joked Yerman. Moments later, his name was called, and he walked onto a professionally lit stage to accept a small crystal trophy from the Oceantic Network, a leading trade group for the burgeoning multibillion-dollar US offshore wind industry.

It was an unlikely sight. America’s fishermen have long treated wind developers as their sworn enemies.

The conflict started in the early 2000s, when the first plans for New England’s offshore wind areas were sketched out. In packed town hall meetings that often devolved into shouting matches, fishermen claimed the projects would make it harder to earn a living: fewer fishing grounds, fewer fish, damaged ocean habitat.

Few of these predictions have come to pass in places like the UK, which has already built over 50 offshore wind farms in its waters. Wind areas there are thriving with sharks and serving as a surprising habitat for haddock. But even today, fisher-led groups in the US are spearheading lawsuits aiming to halt at least two offshore wind farms under construction on the East Coast. One former offshore wind executive told Canary Media that the amount of pushback from fishermen in America has made offshore wind investments riskier than in Europe.

“Everyone knows that fishermen hate offshore wind companies. Well, guess what? Offshore wind companies hate fishermen.”

Yerman was one of the first fishermen in the US to cross this bitter divide. He’s become the reluctant face of a group of over 100 fishermen and fisherwomen who go by the name Sea Services North America. They’ve decided to work for offshore wind farms—not against them. Doing so supplements their income from scalloping, a centuries-old bedrock of the New England fishing economy that has seen revenues dry up.

Pursuing work in wind power has come at a cost. After the awards event, back in blue jeans and with a celebratory beer in hand, Yerman recounted the exact word New England fishermen used when he and his crew first crossed the Rubicon.

“They called us traitors,” he said.

Those tensions have become supercharged with the election of President Donald Trump, who has called offshore wind “garbage” and “bullshit” and, in the weeks leading up to his inauguration, pledged that “no new windmills” would be built in the US during his presidency. He’s backed up those words with action since taking office, stopping new projects from proceeding and attempting to block some of the country’s eight fully permitted offshore wind projects, too.

Yerman and his crew are left wondering if the industry they’ve bet their livelihood on—and work they’ve risked their reputations for—will all come crashing down.

Many of the fishermen who work through Sea Services voted for Trump. And if the president fulfills his promise to halt the industry, it would be devastating not only for the Northeast’s climate goals and grid reliability—but for thousands of workers in the region, from electricians to welders to Sea Services’ fishermen.

One of Sea Services’ captains, Kevin Souza, put it simply: The impact would be “big time.”

Six years ago, Yerman was like the others—angry with offshore wind developers, particularly Danish giant Ørsted, which had set up shop in his hometown of New London, Connecticut.

Concerned that wind turbines might push his son out of the scalloping business, he pulled one of the only levers he could think to pull and contacted his state senator at the time, Paul Formica, a Republican who owned a local seafood restaurant.

Formica wanted to see the two sides get along. He arranged a meeting between Yerman and an Ørsted executive named Matthew Morrissey, who happened to be a native of New Bedford, Massachusetts, the most lucrative commercial fishing port in America.

Yerman found in Morrissey a sympathetic ear, and in turn, he listened to what the executive had to say—that Ørsted was open to partnering with fishermen. Morrissey had seen, with his own eyes, fishers working for and coexisting with Ørsted in a tiny port in Kilkeel, Northern Ireland. The energy firm had a team of about two dozen marine affairs employees, Morrissey relayed, who could help make something like that happen in America if Yerman was on board. He pitched it as a win-win.

“Everyone knows that fishermen hate offshore wind companies. Well, guess what? Offshore wind companies hate fishermen, too,” Morrissey, who no longer works at Ørsted, told Canary Media earlier this year. “Our goal here is to spread the understanding that these two industries can and do and will work together.”

The idea intrigued Yerman. In the US, profits from scalloping have fluctuated from year to year, and, following a crash in the 1990s, scallop numbers remain unpredictable. In his view, if offshore wind companies were moving into their waters—like it or not—they might as well make some money from it.

Yerman got to work.

His first call was to Gordon Videll, a longtime friend and affable small-town lawyer, who knew things about contracts that Yerman didn’t. The two flew to Kilkeel—on their own dime—to see the model for themselves. Videll noticed that some of Kilkeel’s fishermen were driving cars nicer than his. He and Yerman were inspired.

When they returned to Connecticut, Yerman recruited about a half dozen of his commercial fishing buddies, and Videll started putting together the paperwork. They dubbed themselves Sea Services North America and in 2020 landed their first small contract, with Ørsted. It was a pilot, said Morrissey, to see if this arrangement would work here in America.

“Everyone was skeptical,” recalled Morrissey with a laugh. “Because their boats were in such poor safety condition. But you know what? They pulled it off.”

Since taking office in January, President Trump has launched an all-out assault on the offshore wind industry.

Today, Sea Services operates like a co-op and has brought 22 fishing boats up to certified safety standards. With Videll at the helm as part-time CEO, the group has completed over 11 contracts in eight different wind farm areas, from Massachusetts to New Jersey. Instead of hiring ferries or work boats, developers rely on Sea Services fishermen to provide safety and scout services for offshore wind vessels.

It’s important work: making sure, for example, no fishing gear, like crab traps, is in the way of cables, monopiles, or survey operations. If necessary, Sea Services fishermen move gear—with the owner’s approval. When not cleared, these obstacles have caused days and sometimes weeks of costly delays for developers, according to Morrissey.

Sea Services was an “indispensable partner” in helping to build South Fork Wind, which went online last year and became America’s first large-scale offshore wind project, wrote Ed LeBlanc, a current Ørsted executive, in an email to Canary Media. The firm has since contracted the group for other projects, in no small part because of their expertise about local waters, he added.

Cooperation between these two sides—offshore wind and commercial fishing—does exist elsewhere in America. For example, Avangrid and Vineyard Offshore, the codevelopers of the Vineyard Wind project off the coast of Massachusetts, have paid out $8 million directly to local fishermen unaffiliated with Sea Services for similar safety jobs over the past two years.

But Sea Services is unique. Today the group offers an expansive network of 22 partner vessels based in six states and is led by a commercial fisherman. Videll brought on new technology, allowing developers to track their work remotely. He said they adopted a co-op model to maximize the amount of money going into participants’ pockets.

Receiving the Oceantic Network award in late April was a big deal for the collective, said Videll. It’s an example of how successful the venture has been in a short period of time—and, more importantly, it should be good for business. Industry awards mean visibility. More visibility could mean more Sea Services contracts.

But, right now, the Sea Services business faces headwinds that no award can help overcome.

Since taking office in January, President Trump has launched an all-out assault on the offshore wind industry. On his first day in office, he halted new lease and permitting activity and called for a review of the nine projects that already had their federal permits in hand. In March, his Environmental Protection Agency chief revoked a key permit for Atlantic Shores, a fully permitted project that has since been called off in part due to roadblocks created by the administration.

The most eyebrow-raising step came in April, when Trump’s Interior Department issued a stop-work order for Empire Wind 1, two weeks after the project had begun at-sea construction.

It was a wake-up call for Sea Services, which works for Norwegian energy giant Equinor on the project. Videll, Sea Services’ CEO, said at the time that the cessation of Empire Wind would be a crushing blow that could cost the co-op a total of $9 million to $12 million worth of work.

In May, the administration suddenly lifted the stop-work order. Sea Services’ contract was safe, at least for the time being. But it was the most bracing illustration yet that the business, in spite of all its success, now faces very choppy waters under the Trump administration.

On a cloudless late-February day at the New Bedford port, 57-year-old Souza hovered over a checklist and laptop in the captain’s quarters of the Pamela Ann. Souza is the captain of the boat, and he needed to make sure everything was in order before he and his crew left New Bedford that afternoon. They’d be at sea for 10 days, working in many of the spots Souza had fished in for decades.

Those 10 days at sea would not be spent dredging up scallops from the seafloor and tallying their catch, however, but conducting safety operations for the Revolution Wind offshore wind project, which is being built off the coast of Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

The hulking scalloping boat, with its ebony-painted hull and wood-paneled interior, was bustling ahead of the journey. In the galley, Souza’s 25-year-old son, one of the three mates onboard, sorted through the food they’d need. Jack Morris, a 73-year-old scalloper and Sea Services manager, paced around the Pamela Ann checking in on its recently updated safety assets, like a new tracking beacon and safety suits.

Trips like these have become a lifeline for Souza, his crew, and an increasing number of fishermen who depend on the struggling scalloping industry.

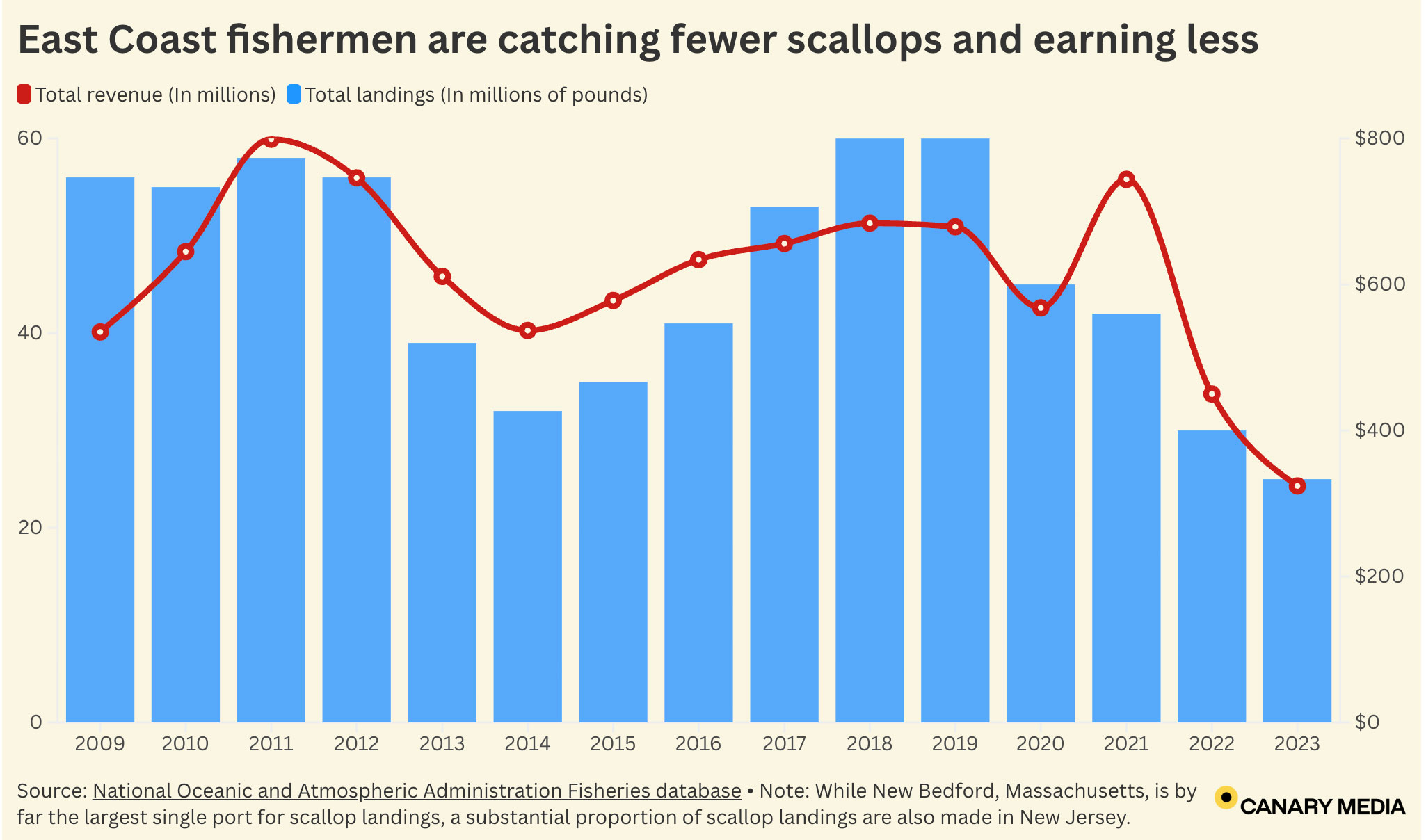

Today, there are roughly 350 vessels sitting in ports from Maine to North Carolina that have licenses to harvest sea scallops. For several decades, East Coast scallopers managed to eke out a comfortable middle-class lifestyle on scalloping alone. Morris said that “years ago” he’d pull in $200,000 to $300,000 of profit annually as a scallop boat captain.

“Yeah, those days are gone,” scoffed Morris.

While the price of scallops remains high, making it one of the most lucrative US fisheries, rules passed over the last 30 years have restricted when and where scallopers can harvest, resulting in fewer days at sea, fewer scallops caught—and less money for the entire industry.

Souza has mixed emotions about the regulations.

On the one hand, scallops are no longer being overfished. A 2024 third-party audit of the fishery said it “meets the requirements for a well-managed and sustainable fishery.” In fact, for over a decade, US sea scallops sold on grocery store shelves have carried a little blue-check label—the mark of a seafood certified by the Marine Stewardship Council.

But most scallop fishermen are now limited to an extremely short window of time during which they can harvest scallops—in 2025, it was just 24 days. Some of their favorite fishing grounds are regularly closed for scallop recovery. There are simply fewer scallops to go around. Souza estimates that captains who stick to scalloping alone are making half of what they did in years past: “They’re probably lucky to make a hundred [thousand].”

Offshore wind work has helped fishermen like Souza and Morris ease the sting of that lost income.

“You’ll have the lobster guys and they’ll say shit to you—like, ‘traitor.’ Or ‘Trump’s gonna shut that down, ha ha ha.’”

Across Revolution Wind’s two-year construction window, Souza expects to make over $200,000 as a part-time boat captain. For the younger generation, who Souza said as deckhands can expect to make only around $30,000 per year from scalloping, offshore wind work makes it possible to keep earning a middle-class wage.

In the past year, Souza has recruited to Sea Services both of his sons, his nephew, and a few other young folks from longtime fishing families who might have otherwise left the scallop industry if not for the supplemental income.

“This wind farm business is the number one way for scallop guys, captains, mates, deckhands, to make extra money,” said Morris.

It’s also helping to revitalize the port of New Bedford, a city of 100,000 that is not only the most valuable fishing port in America but also a place of tremendous historic importance to the industry. It was once the epicenter of the whaling world and serves as the backdrop for the opening scenes of Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick.”

In just 10 years, the offshore wind industry has ushered in a transformation the city hadn’t seen “since the whaling era,” according to Jon Mitchell, the city’s mayor since 2011.

The companies building Vineyard Wind now stage their offshore wind infrastructure in New Bedford. Their presence has brought a flood of public and private funding to the city, with over $1.2 billion already invested and pledged to help give the terminals, docks, and harbor a facelift, according to Mitchell.

For all the money offshore wind has brought to the city—and into the pockets of locals like Souza and Morris—offshore wind remains highly controversial among many commercial fishermen in New Bedford.

That’s in spite of Mitchell’s insistence that, when push comes to shove, New Bedford’s local government will always side with scalloping.

Still, Mitchell, one of New England’s fiercest offshore wind defenders, remains unpopular with many down at the boat docks. “I’ve put myself in the loneliest place in American politics, which is right in the middle. Between offshore wind and commercial fishing,” he said.

The fishermen who take part in Sea Services also float in that lonely place.

It’s not uncommon for them to face harassment from other fishermen over the radio when out on the water, Yerman said. One time, he said a Sea Services fisherman was turned away from a Rhode Island dock, in what Yerman characterized as an act of revenge.

The hardest part of Yerman’s job is overcoming this cultural aversion and getting fishermen to the table, convincing them that working for the offshore wind developers is a way to sustain a livelihood whose viability has begun to fade.

“You’ll have the lobster guys and they’ll say shit to you—like, ‘traitor.’ Or ‘Trump’s gonna shut that down, ha ha ha,’” Souza said, imitating the taunts he receives over the marine radio bolted to the wall near the helm of the Pamela Ann.

The lobstermen have a point regarding Trump. As frustrating as their remarks may be, the biggest threat to offshore wind is not snipes from colleagues, but the actions of a president who many Sea Services members—including Souza—voted for.

Captain Kevin Souza prepared the Pamela Ann, a scallop-fishing vessel docked in New Bedford, for a February excursion.Clare Fieseler/Canary Media

Captain Kevin Souza prepared the Pamela Ann, a scallop-fishing vessel docked in New Bedford, for a February excursion.Clare Fieseler/Canary MediaAs Souza prepared to leave the New Bedford port in February to go help Ørsted build giant wind turbines in the ocean, something Trump swore would not happen during his term, he explained his support for the president.

“Trust me, I want Trump to ‘drill, drill, drill.’ I’m all for it,” said Souza of the president’s plans to expand oil and gas production.

But he still thinks offshore wind is necessary to get more power onto New England’s grid and lower energy costs. Experts say that the federal permitting process for offshore wind in America takes too long—about four years. But, in the Northeast region, according to energy analyst Christian Roselund, finishing the deployment of the offshore wind projects already in the permitting pipeline will be much faster than starting up new nuclear or fossil-gas power plants.

“Once we ‘drill, drill, drill,’ you’re still gonna need more electricity,” Souza said. “Where are you gonna get it? My electric bill at my house is stupid high!”

“When you put that first wind turbine up there,” Avila recalls other fisherman saying to him, “we’re going to hang you from it!”

Most of the fishermen in New Bedford are Trump supporters, he insisted. Morris, who also voted for Trump, agreed. Overall, Trump won 46% of the city’s votes in last November’s election—a much higher proportion than his Massachusetts statewide total of 36.5%. The “TRUMP 2024” flags flown from the dozens of scallop boats docked across New Bedford’s port underscored the point. A few of those Trump flag-flying boats even work for the offshore wind companies, Morris claims. ThePamela Ann, for its part,does not have a Trump flag.

“I support Trump even though I know he’s against wind. … I believe this will still be around,” said Souza, gesturing toward the ocean, where somewhere over the horizon an array of wind towers was being erected. “He’s gonna see the light.”

Trump, of course, has not seen the light—though he did revoke his stop-work order against Empire Wind.

After being grounded for a month, Sea Services fishermen began operations on Empire Wind again in early June, when the project resumed at-sea work. The co-op’s members are helping Equinor’s construction vessels lay boulders on the seafloor to stabilize all 54 wind towers that will be raised over the next two years and eventually supply much-needed carbon-free power to New York City.

But nothing is certain. When the Trump administration unpaused the project, it left open the door to stopping it again—or killing it altogether. A May letter from the Interior Department to Equinor noted that it is still conducting an “ongoing review” to determine if the project’s permits were “rushed” and therefore illegitimate in the eyes of the Trump administration.

Meanwhile, a coalition of a dozen fishing companies and several anti-offshore wind groups typically allied with Trump sued the administration on June 3, just days before Empire Wind restarted at-sea construction, in an attempt to reinstate the stop-work order. The move came weeks after wind opponents asked Trump to also pause Revolution Wind, one of the more lucrative contracts Sea Services holds.

In his opposition to offshore wind, Trump has positioned himself as a defender of the commercial fishing industry, claiming falsely at a May 2024 campaign rally in Wildwood, New Jersey, for example, that the turbines “cause tremendous problems with the fish and the whales.”

But for the increasing number of fishermen working with offshore wind companies, halting the industry would not help—it would crush a financial lifeline.

Not long ago, in 2017, Sea Services captain Rodney Avila remembers being one of the only fishers in New Bedford willing to seize this lifeline. He recalled with a laugh what a long-time fisherman friend said to him then: “When you put that first wind turbine up there…we’re going to hang you from it!”

Times have changed. In New Bedford alone, almost 50 local fishing vessels have performed some kind of safety or scouting work for offshore wind projects. At least one captain lowers his MAGA-supporting flag before setting out to work on the projects the president has sworn to stop, according to Avila. He said politics has always been tangled up in fishing. And work is work.

“They don’t care whether it’s red, or blue, or whatever color…They don’t care,” Avila shrugged, while sipping coffee inside a Dunkin’. Five scalloping boats bobbed on calm water just beyond the parking lot.

“It’s money that they need to support their families, wherever it comes from.”