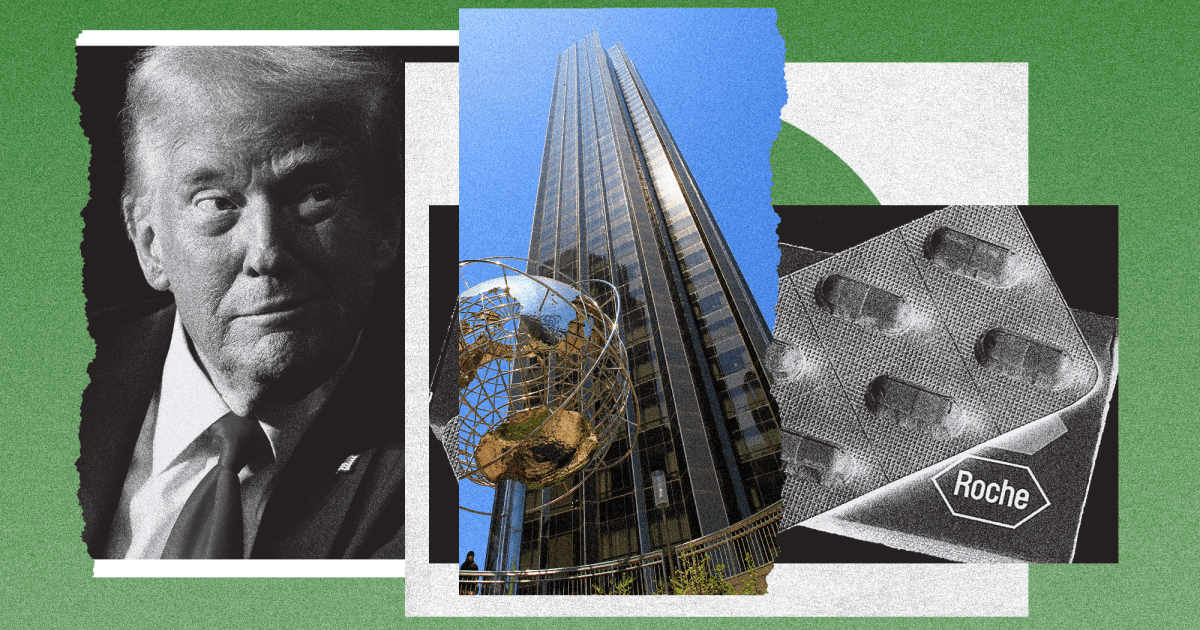

Donald Trump’s realty firm is representing one of the country’s largest pharmaceutical companies in its effort to offload a $12 million New York condo—an arrangement that represents yet another apparent conflict of interest for the 47th president of the United States.

The condo on the 39th floor of the Trump International Hotel and Tower at Columbus Circle has been on and off the market for several years but hasn’t been successfully sold. According to real estate websites, it was listed by a different realty firm, Sotheby’s, until late last month. Around that time, it was listed for sale on Trump International Realty’s website. If it sells at its current listing price, it would likely earn hundreds of thousands of dollars in commissions for Trump’s firm.

According to New York real estate records, the Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche bought the swanky 3,000-square-foot condo back in 2006. The two-bedroom unit features “sweeping views of Central Park,” along with “lacquered custom tray ceilings with custom lighting, custom pocket doors, Steinway black lacquered doors, Corian counters, subzero refrigerator, Wolf convection oven, wine cooler and marble bath.” It’s unclear why Roche—which has offices across the United States—originally purchased the property or why it recently turned to Trump’s real estate firm for help. Roche and its American biotech subsidiary, Genentech, did not respond to requests for comment. Nor did the Trump Organization or Karina Lynch, an attorney with the powerhouse firm DLA Piper, who was recently announced as the Trump Organization’s “outside ethics adviser.”

Trump International Realty is far from the president’s most profitable venture, but it’s still plenty lucrative. Boasting a “luxury portfolio” full of “exclusive listings,” the firm pulled in $2.4 million in revenue last year, according to Trump’s most recent financial disclosure filing. Trump owns 55 percent of the firm, and his children own the rest. It currently lists 10 properties for sale in New York, with a combined listed price of $42.6 million. Most are in Trump-branded luxury buildings.

The Roche condo is, by far, the priciest unit. But the second-most expensive—a $6.6 million condo in a nearby building known as Trump Parc—also raises some questions. According to real estate records, that unit has been owned since 2001 by a British Virgin Islands-based company. The identity of the individual or individuals behind that company are unclear. An accountant whose name appears on the deed did not respond to a request for comment.

The amount of commission a realty firm earns on a property sale can vary, but real estate websites say the typical seller’s commission in New York is around 2.7 percent. At that rate, selling Roche’s condo for the asking price of $11,950,000 could earn the Trumps’ realty business about $323,000 in commissions. And selling the mysterious Trump Parc condo could bring in another $178,000. It’s not clear what portion of those commissions would go directly to the individual real estate agents employed by Trump International Realty and what portion would be retained by the Trumps.

Roche has massive and complex interests in Washington, DC, and the Trump administration has considerable authority over the price of pharmaceuticals and the approval of new products. The drugmaker is one of heaviest spenders on K Street, with the company and its subsidiaries shelling out more than $10.7 million on lobbying expenses last year. In the first three months of 2025, the company reported nearly $3.6 million in federal lobbying. Most of that spending went to Genentech’s in-house lobbying team. In March, Genentech also hired MAGA-linked K Street firm Miller Strategies to lobby the Executive Office of the President and other parts of the administration. Roche’s overall spending this year on lobbyists ranks 6th in the pharmaceutical industry and just outside the top 25 of any special interest.

The possibility that one of Trump’s businesses could collect a substantial commission from a major corporation during his presidency is deeply problematic, says Robert Maguire, research director for Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, a watchdog group.

“The optics are terrible, but there’s also all of the unanswerable questions which are raised by it, like did someone tell them that by enriching the president, they’d have a better chance of having their interests heard by the administration?” Maguire says. “Or is there just a general perception that if you do business with the president, if you enrich the president, you will get better treatment by the administration?”

Even if the decision by Roche to list its condo for sale with the sitting president’s realty firm was unrelated to politics, it could undermine public confidence in the integrity of the regulatory system, Maguire says.

Roche has had its fair share of high-stakes dealing with the Trump administration over the last few months. As a Swiss-based drug company, it potentially has a lot to lose from Trump’s tariffs—the standard tariff of 10 percent is supposed to rise to 31 percent on many of its products. In April, Roche made a splash by announcing it would be investing up to $50 billion in the United States and creating as many as 12,000 jobs—a move that would theoretically help it avoid tariffs by moving some manufacturing to the US. The company’s CEO told investors that the firm was in ongoing discussions with the White House about the tariffs, and a few days later, Roche’s announcement earned praise from the administration.

In May, Trump signed an executive order that attempted to force pharmaceutical companies to tie their US drug prices to the prices they charge in other developed countries. Roche was one of the first—and loudest—companies to complain about the move.

By early June, though, the company’s US investment plans were once again being touted by the administration. “Since President Donald J. Trump took office,” the White House crowed, “his unwavering commitment to revitalizing American industry has spurred trillions of dollars of investments in US manufacturing, production, and innovation—and the list only continues to grow.”

Ethics experts have long urged Trump to divest from his businesses, but he has steadfastly refused to do so. As Maguire notes, conflict-of-interest rules would prohibit any federal official other than the president and vice president from hanging onto a business like Trump International Realty.

“He’s the president, so he’s exempted from any of these rules that would apply to other people—hundreds of thousands of other government employees would be restrained or prohibited from this kind of thing,” Maguire says. “It’s just another instance of how at every turn, the Trump family and their businesses are demonstrating why these rules exist in the first place.”