Subscribe to Mother Jones podcasts on Apple Podcasts or your favorite podcast app.

A few days after the 2024 election, Zohran Mamdani filmed the first video in a mayoral campaign that would come to be defined by them. Standing on street corners in the Bronx and Queens, the 33-year-old Democratic-Socialist state assemblyman asked a procession of New Yorkers two simple questions: Who had they voted for, and why?

There was nary a MAGA hat in sight. But voter after voter—across a range of ages and backgrounds—explained that they’d either voted for Trump, or not voted at all. They were fed up with the rising cost of living. They wanted an end to the war in Gaza. And they felt like they were getting nothing from Democratic leaders.

The video, which has more than 2.6 million views on X, was both self-serving and illuminating—a campaign soft-launch rooted in a simple reality: If you want to understand the hole the Democratic Party is currently in, you have to get out of your swing-state bubble and join the Real Americans on the subway. The biggest on-the-ground development of the 2024 election was what happened in the places Democrats took for granted. In blue cities in blue states, President Donald Trump improved his performance among working-class non-white voters while Democratic support fell off dramatically. Trump’s popular-vote victory was an earthquake. And New York City was its epicenter.

Trump picked up nearly 100,000 more votes in his home city than he did four years earlier—while Kamala Harris ran more than half a million votes behind Joe Biden. And the more immigrant and working-class a neighborhood was, the greater the dropoff. The three congressional districts with the biggest swings toward Trump in the entire country last year were all in Queens or the Bronx (or both, in the case of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s 14th district). While the city and the state stayed comfortably blue, the results embodied a worrisome national trend for Trump’s opposition: The places where support for Democrats eroded the fastest were also the places where they have been in power the longest.

On Tuesday, New York City voters will cast their ballots again, in the biggest contest yet of the party’s post-Trump reset—the Democratic mayoral primary. The race has been, in a lot of ways, a characteristically local affair. The word “re-zoning” comes up a lot. Depending on who you ask, it’s a referendum on Mamdani’s inexperience, former governor Andrew Cuomo’s record of bullying and sexual harassment, or current mayor Eric Adams’ alleged crimes. But it’s also a referendum on where people in America’s biggest Democratic enclave think the Democratic Party went wrong.

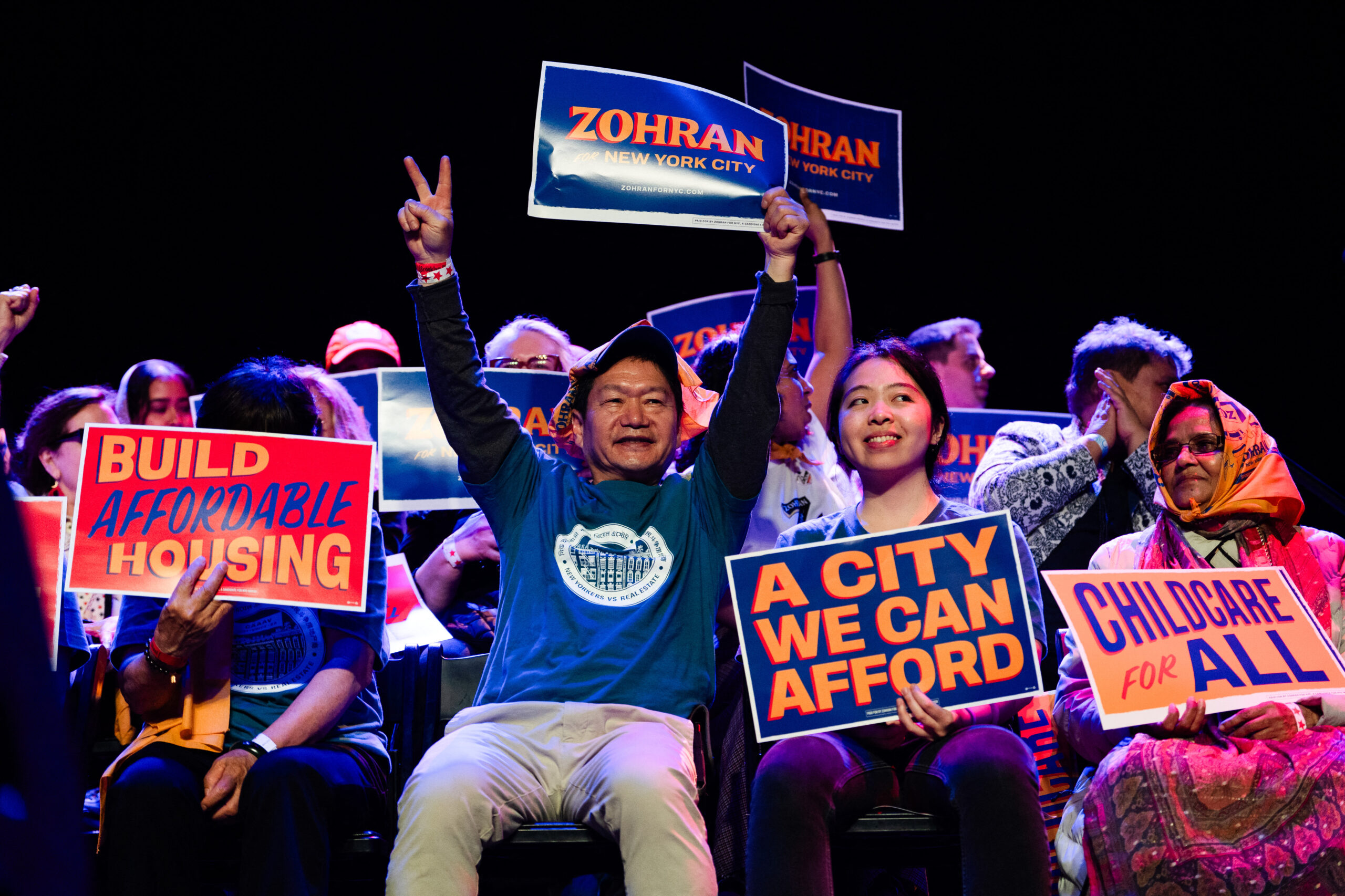

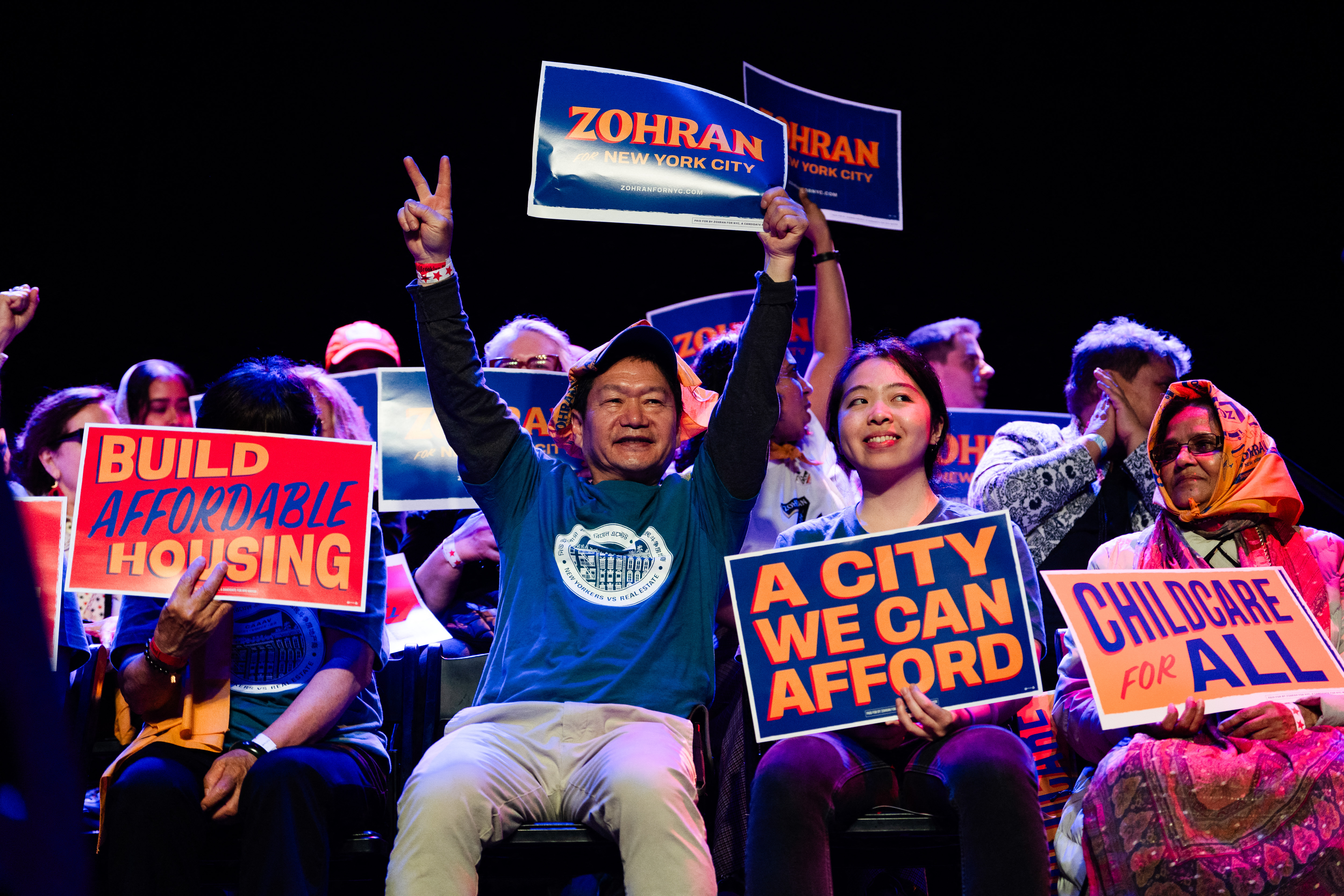

You may not be surprised to learn that Mamdani and Cuomo both think the answer is the other guy. At a rally in Brooklyn last month, in a former steel plant that’s been converted into a concert venue, supporters wore buttons touting Mamdani’s campaign promises—free buses, free childcare, freeze the rent—and swag from the local chapter of Democratic Socialists of America. Aside from a few taxi drivers (whom Mamdani had joined on a hunger strike in 2021), and the candidate’s famous filmmaker mom, it was hard to find anyone who looked older than 40.

“I have a lot of friends in this field—except Cuomo” the Mamdani-endorsing Bronx state Sen. Gustavo Rivera told me, while the actor and Obama White House staffer Kal Penn emceed from the stage. “Cuomo is a piece of human garbage.”

Rivera repeated it again, in a sing-song voice this time, to make sure I got the message: “a piece of hu-man gar-bage, who’s an abu-sive bul-ly, who does not deserve to be anywhere near public ser-vice.”

The three congressional districts with the biggest swings toward Trump in the entire country last year were all in Queens or the Bronx.

Cuomo, the frontrunner, resigned his office in 2021 after an investigation by the state attorney general’s office found that he had sexually harassed 11 women—charges he disputes and says are politically motivated “cancel culture.” To Mamdani and a substantial subset of Democratic voters, Cuomo is the embodiment of how Democrats ended up in their current predicament.

“Democrats are tired of being told by leaders from the past that we should continue to simply wait our turn, we should continue to simply trust, when we know that’s the very leadership that got us to this point,” he said at a debate in June. “We need to turn the page for new leadership to take us out of it.”

Mamdani’s campaign is built on addressing what he calls the city’s “affordability crisis”—allowed to fester for too long by Democratic leaders, he believes—with a series of fits-on-a-button proposals that would require some combination of tax increases and political finesse to implement. But Mamdani is also at the vanguard of a generational challenge to the city and state’s old-guard Democratic leadership that’s been brewing since the last shock Trump victory.

Cuomo spent years steamrolling his liberal critics as governor. He refused to even shake law professor Zephyr Teachout’s hand in 2014, while a top ally belittled the actress Cynthia Nixon as an “unqualified lesbian” four years later. Those progressives, in turn, believed New York was Blue America’s missed opportunity—a place mired in mediocrity by craven, corrupt, or just out-of-touch party leaders. This lack of ambition was epitomized by Cuomo’s support for members of the Independent Democratic Conference, a rogue faction of state senators who gave Republicans control of the chamber in exchange for legislative perks.

But in 2018, even as Cuomo cruised to re-election, progressive challengers knocked off six incumbent state senators in the primaries—mostly in the outer boroughs—and helped cement one-party Democratic control of the state government. The biggest jolt came that June, when a Democratic-Socialist bartender, Ocasio-Cortez, upset 10-term Rep. Joe Crowley—the chairman of the Queens Democratic Party. Those wins announced a new force in New York Democratic politics—youthful, diverse, and hungry to do things Democrats had been too timid to try.

“Along the 7 line in Queens, a new Democratic politics is born,” Bloomberg announced that summer. Local DSA members borrowed a slogan from a famous mural in the neighborhood of Jackson Heights: “Queens is the future.”

Cuomo’s theory of the race—notwithstanding the fact that he was elected governor three times, his dad was governor, and he has the backing of a bipartisan assemblage of billionaires—is that the party’s plummeting fortunes have less to do with him than with the people who don’t like him.

“They want to go further left. My argument is no, we lost because we were too far left,” he said at a private event earlier this year. “Because we were talking about bathrooms and who was gonna play on what team, boys and girls, you lose touch on what people care about, which is safety.” Cuomo has said that “Defund the police are the three dumbest words ever uttered in politics.” And he’s warned that if taxes on the city’s highest earners are raised like Mamdani wants, “the rich will move to Massachusetts.”

It’s a message that echoes what a lot of other national Democratic leaders have been saying since November—people like former Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel and California Gov. Gavin Newsom. Cuomo’s campaign launch video was the apocalyptic inverse of Mamdani’s man-on-the-street missive, invoking both the post-pandemic uptick in violent crime (which is now dropping) and the arrival of 230,000 migrant crisis in the city over a two-year period.

“You feel it when you walk down the street and try not to make eye contact with a mentally ill homeless person,” Cuomo says in the video, staring directly into the camera. “Or when the anxiety rises up in your chest as you’re walking down into the subway. You see it in the graffiti, the grime, the migrant influx, the random violence. The city just feels threatening, out of control, and in crisis.”

It’s a bit more complicated than that. Homelessness is a product of a housing crisis Cuomo presided over, he took money from the subway as governor to bail out ski resorts, and the bail-reform law vilified by some New Yorkers bore his signature. But the pitch is the pitch. The party’s non-white working-class base, he argued, was “paying the highest price for New York’s failed Democratic leadership.”

If Queens is the future, what exactly is the future telling us? To understand how Democrats lost their groove in New York, I went back to the place where things seemed to be going so well for progressives—the heavily immigrant neighborhoods of Queens that produced Ocasio-Cortez’s 2018 upset. Over the last few months, my colleagues and I spent lot of time talking to residents and elected officials in the neighborhoods of Corona and Jackson Heights for a recent episode of Reveal.

Just off the 7 train on Roosevelt Avenue—the dividing line between AOC’s district and that of Rep. Grace Meng (which also swung 23 points to the right at the presidential level last year)—Trump carried some precincts where he won just a quarter of the vote in 2020. This part of Queens embodied the kinds of places Democrats suffered the most nationally: A large percentage of residents are first- or second-generation immigrants of Latin American or Asian descent, and a comparatively low percentage of voters have college degrees. By one projection, naturalized citizens swung 20 points toward the president last year, while Latino men shifted toward Trump by 16 points.

Part of the story is that while the surrounding neighborhoods formed the symbolic backbone of the city’s new-left politics—Ocasio-Cortez’s campaign hawks stylish Green New Deal prints, depicting high-speed trains whooshing through nearby Flushing Meadows Corona Park—Roosevelt Ave. was also becoming a powerful symbol on the right of perceived failures of progressive governance over the last few years.

“When you have a former president promising us we are gonna have immigration reform within the first a hundred days and four years later, we have nothing to show for it, people remember that.”

The “influx of migrants” Cuomo mentioned in that video were not evenly distributed across the city. Many of the newcomers, particularly Venezuelans, ended up in places like Corona, where they jostled for space with existing residents and struggled to make ends meet. (Asylum seekers are legally barred from seeking employment for about six months after applying for protection.) Many new immigrants tried to find work as street vendors, but lacked permits. (So did many vendors regardless of immigration status, due to a broken city permitting process—an example of dysfunctional bureaucracy Mamdani has zeroed in on in his campaign). Fox News devoted regular coverage to complaints about trash, crime, and sex workers in the area. It should have been easy to see a backlash coming down the pike. In the final weeks before the presidential election, Roosevelt Avenue’s “numerous brothels” were a punchline on Saturday Night Live.

“I think many people were experiencing and seeing crime go up,” said Jessica González-Rojas, a Democrat who represents part of the area in the state assembly. “With a lot of new arrivals, people were resentful, even those who were immigrants that have been around for generations. I think folks felt like their needs weren’t being addressed, which were the very material needs of the rising prices for food and groceries, rising costs of rent and housing, and again, the increases in crime. Many of us who are progressive have been talking about that, but I think it wasn’t resonating in those same ways.”

People felt squeezed on every front. Inflaming all of this was a sense that government hadn’t been there for people when they needed it. The pandemic came up over and over in our conversations. The area was “the epicenter of the epicenter,” as González-Rojas put it—and not by accident. “Essential workers” continued showing up to their jobs while more affluent, white-collar voters adjusted to Zoom. At Elmhurst Hospital, just a few blocks off Roosevelt Ave., so many people died in the first weeks of the pandemic that a mobile morgue unit set up outside. The hospital has just one bed for every thousand residents, noted Shekar Krishnan, the area’s Democratic city councilman, and it was the only facility serving the area. It’s hard to be the party of the social contract when the social contract is in tatters.

“There was a sense of almost lawlessness, right?” González-Rojas said. “Like you saw people blow through red lights. Crime ticked up. There was just a lack of order that something about the pandemic caused.”

Catalina Cruz, a progressive who represents a neighboring assembly district that includes parts of Corona argued that the pandemic response “had a lot of people disillusioned with government.” Ongoing detachment and disinvestment was layered onto existing inequities, and raised questions about who politicians really worked for. “Andrew Cuomo never stepped foot in Corona. Even during the pandemic, I had to fight him to get a vaccination site in my district. I had to fight him and [former mayor] Bill de Blasio.” (Politico recently reported that Cuomo had in fact attempted to block a vaccination site from opening at nearby Citi Field, because the site was de Blasio’s idea and not his.)

What exactly you think of as “disorder” can vary a lot. But it’s something that everyone from the progressives to the reactionaries seemed to agree there was more of after the pandemic—or at least that people felt like there was more of. And there was a propulsive quality to that anxiety. A recent piece in Vital City called New York City’s malaise an example of “negative social contagion”—essentially, the city has been so overwhelmed by bad vibes that the bad vibes were beginning to call the shots.

When we talked to shopkeepers in Corona about what they wanted from the next mayor, public safety was the top concern. It wasn’t just a bit of New York Post-driven hysteria: Major felonies nearly doubled in this police precinct after the pandemic. An Ecuadorean immigrant who sold soccer jerseys said she had been robbed three times in the last few years. Another voter we spoke with, a formerly undocumented immigrant named Mauricio Zamora who had voted for Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Joe Biden after getting his citizenship, told us he switched to Trump because he felt like Democrats weren’t doing enough about crime. He’d formed a local community group to agitate against sex workers and “vagrants,” and he was leaning toward Cuomo.

There’s plenty for progressives to grapple with in stories like these. The fact that Mamdani is facing millions of dollars in attack ads featuring a five-year-old call to “#DefundtheNYPD” perhaps offers some lessons for aspiring lefty politicians when it comes to public safety messaging. But New York’s uneasy lurch presents a lot of challenges for status-quo Democrats too. These neighborhoods offer a glimpse of what happens when you don’t deliver on progressive policy promises—and when people feel ignored by their leaders. Zamora, for instance, supported a path to citizenship for undocumented residents, and was so frustrated that none of the Democrats he’d voted for in the past had delivered on it that he had stopped believing their promises.

“When you have a former president promising us we are gonna have immigration reform within the first a hundred days and four years later, we have nothing to show for it, people remember that,” Cruz, who was once undocumented herself, said of Biden. To her, national Democrats were dealing with the fruits of patronizing and ultimately empty leadership. Instead of showing up, they were just “sending 10,000 text messages telling us that it’s doomsday because we’re not sending $10 for you to do whatever the hell you’re doing.”

It’s hard to overstate just how dysfunctional the party is in the city and the state. In 1953, 93 percent of eligible voters participated in the mayoral election; in 2021, just 23 percent did. That disengagement is part of what made the left’s outer-borough rise possible—AOC won her primary in 2018 through hard work, yes, but also because the head of the Queens Democratic Party couldn’t even rustle up 13,000 people to vote for him. The New York State Democratic Party spent money on a 2018 primary mailer accusing Cynthia Nixon of enabling anti-semitism (which the party said was a mistake), but then spent nothing on three losing statewide ballot initiatives in 2021. Afterwards, Jay Jacobs, the party’s Cuomo-loving chair, explained that it had only spent $0 on key Democratic priorities conservatives had spent nine-figures attacking because no one had asked the party to spend more.

Faced with the fruits of their poor choices, party leaders have sometimes made peace with mediocrity. “We did well in Southern Brooklyn,” Brooklyn Democratic Party chair Rodneyse Bichotte Hermelyn—a Cuomo-backing state assemblywoman—said in November, after an election in which Democrats lost a state senate seat in the borough for the first time in eight years, and failed to even field a candidate in an assembly district where Democrats held a three-to-one registration advantage over Republicans. “He did a great job as chair, and he continues as chair,” Gov. Kathy Hochul said of Jacobs, after the party’s table-setting collapse in the midterms two years earlier. Last September, with the party careening toward another setback, Jacobs was reelected to his post again.

The problems of disillusionment and disengagement are particularly salient in New York, but they are a problem for Democrats in blue cities more broadly. In the counties that include Los Angeles and Chicago, nearly a million Democrats stayed home in 2024—and support fell dramatically in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods. Just 16.5 percent of voters showed up for a recent municipal election in Philadelphia, where flagging turnout and eroding support helped cost Democrats a Senate seat last year. (“Turnout doesn’t bother me, only bothers me [that] we win” Bob Brady, the city’s Democratic party boss, told the Philadelphia Inquirer.) Even more than the choice between Cuomo and Mamdani, the biggest indicator of whether Democrats are getting their act together might be how many of them show up to vote at all.

That’s not to say that everything happening in New York tells a story about everywhere else. This is a place that just discovered the existence of trash bins, but still can’t decide whether they’re good or not. (If elected, Cuomo has said he would scrap containerization requirements for “small properties.”) But all of the crosscurrents that have swamped the party over the last eight years are present in New York in an unavoidable way. It’s a test not just of left vs. center, but of the desire for change vs. doubling down, of new blood vs. wait-your-turn, of outsiders vs. insiders. This is where the pandemic hit hardest, first, and where the tangled immigration policies of the Biden era viscerally fell apart. Crime, housing costs, grocery bills, apathy—these were the tests Democrats failed in their backyards before they failed everywhere else.

For a long time, it has been tempting, in a world of red-and-blue electoral maps and swing-state fixations, for politicians to alternatively write off places like New York and take them for granted—a wellspring of safe votes and big checks. But the lesson of 2024 was a cautionary one: If you can’t make it here, you can’t make it anywhere.

Additional reporting by Noah Lanard and Nadia Hamdan.