Visit a mountain trailhead here in western Montana right now, and you might be treated to an unusual sight: car-size white cylinders. Those are grizzly capture devices, and they’re being staged ahead of a summer-long effort to count the bears and evaluate the ongoing success of a 40-year plan to restore their population across the northern Rockies. This year may be a pivotal moment for that population, as a number of the regulations and programs protecting them currently hang in the balance. Those include staffing levels among the scientists who study them, rules governing how humans defend themselves from the bears, and protections provided by the Endangered Species Act (ESA) itself. Meanwhile, logging operations are being sped through permitting processes in the places where bears live, threatening both habitat and birth rates.

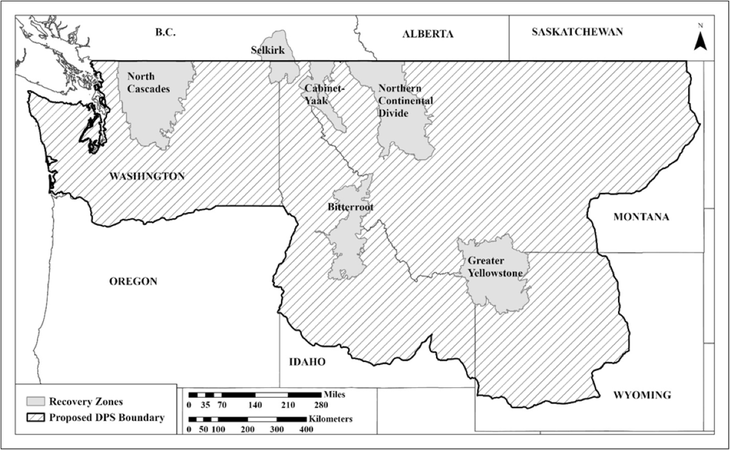

Uncertainty has been part of grizzly preservation efforts since the beginning. In fact, fewer than 1,000 bears remained in the Lower 48 when the ESA first listed grizzlies as threatened in 1975. At the time, scientists acknowledged that neither of the isolated populations that lived around Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks could ever grow big enough on their own to achieve a sustainable level of genetic diversity. But connecting them seemed impossible. The two groups were separated by the entire state of Montana—including highways, towns, human populations, and large swaths of private property. In much of that territory, grizzly reintroduction efforts were highly contentious. That’s why a recovery plan for the species, published in 1982 and revised in 1993, was written with a focus on growing the individual populations in each of those disconnected ecosystems, rather than trying to bridge them across hundreds of miles of anti-predator West.

The 1993 plan was groundbreaking—and massively controversial. It began with an excerpt from an essay written by famed ecologist Aldo Leopold:

“The grizzly bear is a symbolic and living embodiment of wild nature uncontrolled by man. Entering into grizzly country represents a unique opportunity—to be part of an ecosystem in which man is not necessarily the dominant species.”

What followed: decades of argument about whether or not the species had recovered, and when, how, and why the grizzly might be removed from ESA protections, as well as the purpose of the ESA itself.

All that seemed to culminate in 2017, when then-Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke announced a plan to de-list the bears from the ranks of species protected by the ESA.

“This achievement stands as one of America’s great conservation successes; the culmination of decades of hard work and dedication on the part of the state, tribal, federal, and private partners,” Zinke stated at the time.

Those private and tribal partners filed suit immediately, resulting in a 2018 ruling that saw the ESA protections for grizzly populations in the Lower 48 restored, a decision that still stands today.

But no discussion of a large omnivore that can grow in excess of 500 pounds can stop at policy. While all that bickering was going on, grizzly populations expanded in both numbers and area. The bears’ populations have doubled since the 1970s, and they now wander into their historic habitat on the prairies east of the mountains. There, they cause conflict in places where generations of humans have become accustomed to their absence.

Just last week, a sow charged two men foraging for mushrooms on their property north of Choteau, Montana, a small town about 25 miles from the mountains, where winding creeks cut through rolling hills as they fade into grasslands. The men shot the charging bear dead.

Such conflicts fuel demands for delisting. Ask people who live here in grizzly habitat—my wife and I split time between Bozeman, which butts up against the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and a property bordering the east side of Glacier National Park where bears are a part of everyday life—and many people would say we’d be better off without them.

At the beginning of the year, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service sparked a ton of controversy on both sides of the grizzly debate by proposing a rule that would manage all grizzly populations in the Lower 48 as a single, federally protected population under the ESA. Pro-grizzly people loved the acknowledgement that grizzlies are a single population—but they loathed a further provision intended to provide more flexibility for ranchers and land owners hoping to manage grizzly conflicts on their own terms.

This latter provision would allow land owners and livestock managers to “take” (read: kill) bears under some conditions—in addition to self-defense—without first applying for a permit. The rule would also expand the definition of self-defense to include “non-immediate” threats to safety.

Soon after the new administration came into office in Washington D.C., public hearings around that rule were cancelled, but the public comment period was extended through May 16. More than 76,000 people participated.

Andrea Zaccardi, the Center for Biological Diversity’s legal director of carnivore conservation, explains the deadline for final rule-making is January 2026. While the Trump administration has been uncharacteristically quiet about its intentions for the plan, it could represent a sea change for grizzly management.

Since 1970, grizzly research and management efforts have been led by a federal office called the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team (IGBST). Amid efforts to make the federal government more efficient, the IGBST is reportedly facing closure, leaving its future unclear—and with it the very research that informs grizzly bear policy

Change could also be coming to the ESA, the legal foundation for grizzly protection. Some legislators have proposed a new definition of “harm” when it comes to endangered species. Under this new definition, destroying a protected species’ habitat would no longer be illegal.

The Center of Biological Diversity’s Zaccardi says she fears that this change, along with an emergency order to massively expand logging operations on public lands, could represent a significant threat to the long-term success of grizzly populations.

“Logging hurts bears,” she told me during a phone call, going on to explain that beyond the simple destruction of grizzly habitat, logging operations cause bears to expend additional energy to leave the area, that the people logging brings into bear habitat creates risk of conflict, and that the road construction necessitated by logging creates longterm impacts even after timber harvests are completed.

“Expending that energy significantly decreases birth rates,” she added. “And grizzly bears really don’t like roads.”

Those roads bring everything from disturbances created by vehicles and heavy equipment to pressure from humans engaging in outdoor recreation into new places, forcing the bears out. The USDA is hoping to expand logging operations across 112 million acres of National Forest, a significant portion of which is grizzly habitat in the northern Rockies.

Even given that very uncertain picture, Zaccardi remains optimistic about the grizzly’s prospects. “They’re a resilient species,” she says. And this is far from the first time things have looked uncertain for the bears in the five decades people have been working to save them.

The post Grizzly Recovery Efforts, Once Booming, Now Face Limbo appeared first on Outside Online.