How much nori, dulse, or arame approximates the recommended daily allowance for iodine?

Dairy milk supplies between a quarter and a half of the daily iodine requirement in the United States, though milk itself has “little native iodine.” The iodine content in cow’s milk is mainly determined by factors like “the application of iodine-containing teat disinfectants,” and the “iodine residues in milk originate mainly from the contamination of the teat surface…” Indeed, the teats of dairy cows are typically sprayed or dipped with betadine-type disinfectants, and the iodine just kind of leaches into their milk, as you can see at 0:35 in my video Friday Favorites: The Healthiest Natural Source of Iodine.

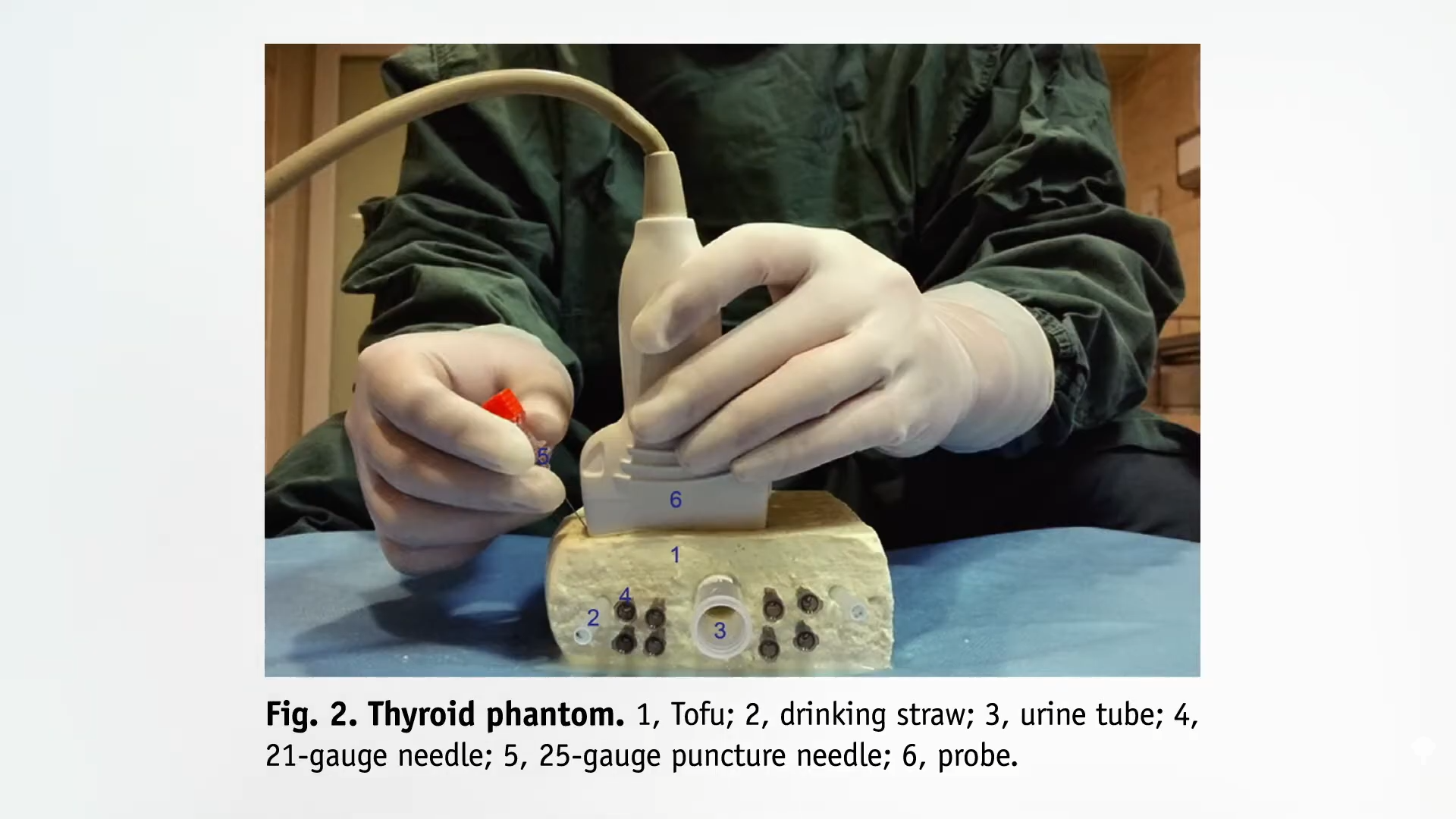

Too bad most of the plant-based milks on the market aren’t enriched with iodine, too. Fortified soy milk is probably the healthiest of the plant milks, but even if it were enriched with iodine, what about the effects soy may have on thyroid function? When I searched the medical literature on soy and thyroid, this study popped up: “A Cost-Effective, Easily Available Tofu Model for Training Residents in Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Thyroid Nodule Targeting Punctures”—an economical way to train residents to do thyroid biopsies by sticking the ultrasound probe right on top a block of tofu and get to business, as you can see below and at 1:10 in my video. It turns out that our thyroid gland looks a lot like tofu on ultrasound.

Anyway, “the idea that soya may influence thyroid function originated over eight decades ago when marked thyroid enlargement was seen in rats fed raw soybeans.” (People living in Asian countries have consumed soy foods for centuries, though, “with no perceptible thyrotoxic effects,” which certainly suggests their safety.) The bottom line is that there does not seem to be a problem for people who have normal thyroid function. However, soy foods may inhibit the oral absorption of Synthroid and other thyroid hormone replacement drugs, but so do all foods. That’s why we tell patients to take it on an empty stomach. But you also have to be getting enough iodine, so it may be particularly “important for soy food consumers to make sure their intake of iodine is adequate.”

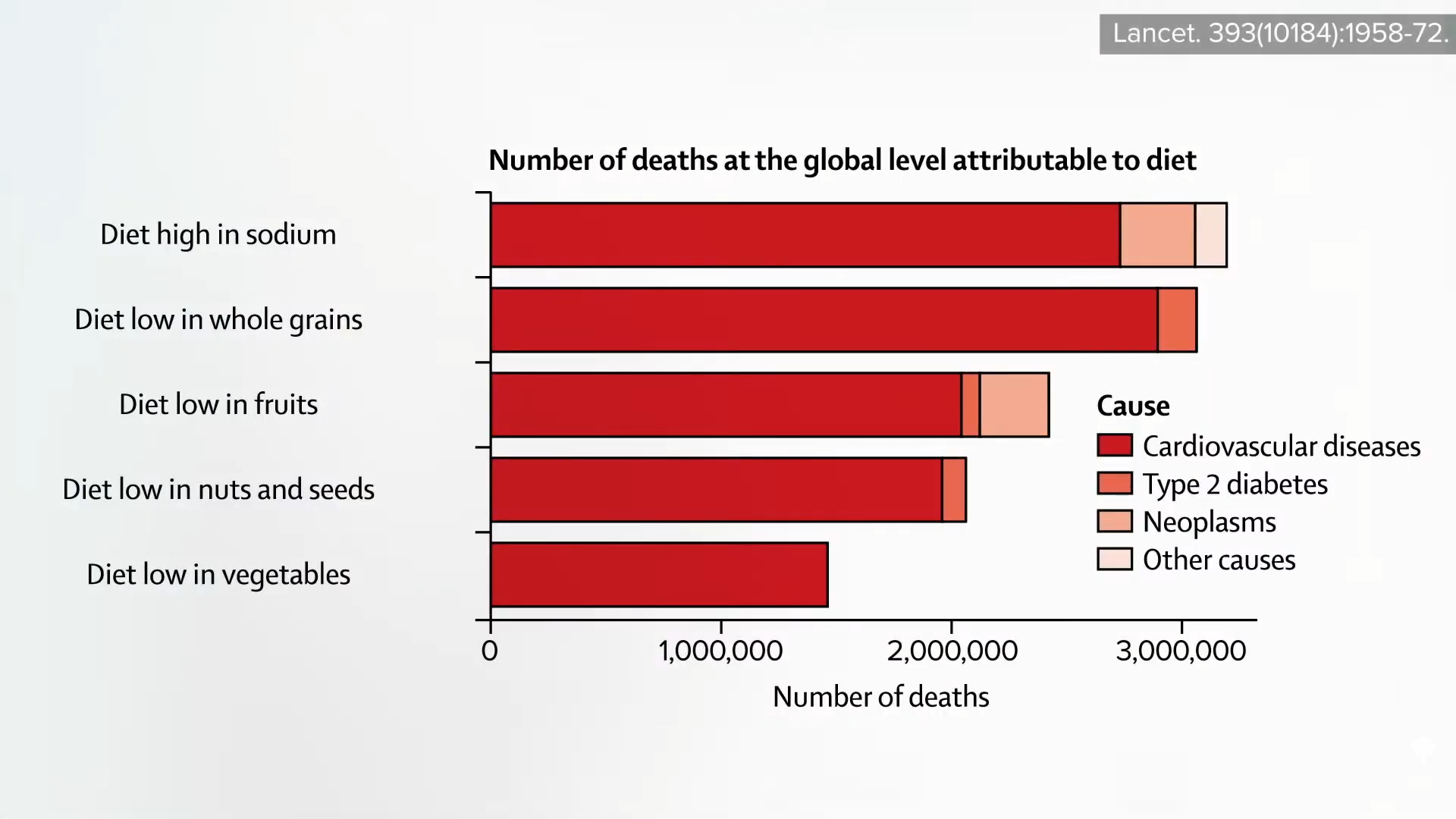

What’s the best way to get iodine? For those who use table salt, make sure it’s iodized. “Currently, only 53% of salt sold for use in homes contains iodine, and salt used in processed foods typically is not iodized.” Ideally, we shouldn’t add any salt at all, of course, since it is “a public health hazard.” A paper was titled: “Salt, the Neglected Silent Killer.” Think it’s a little over the top? Dietary salt is the number one dietary risk factor for death on planet Earth, wiping out more than three million people a year, twice as bad as not eating your vegetables, as you can see here and at 2:38 in my video.

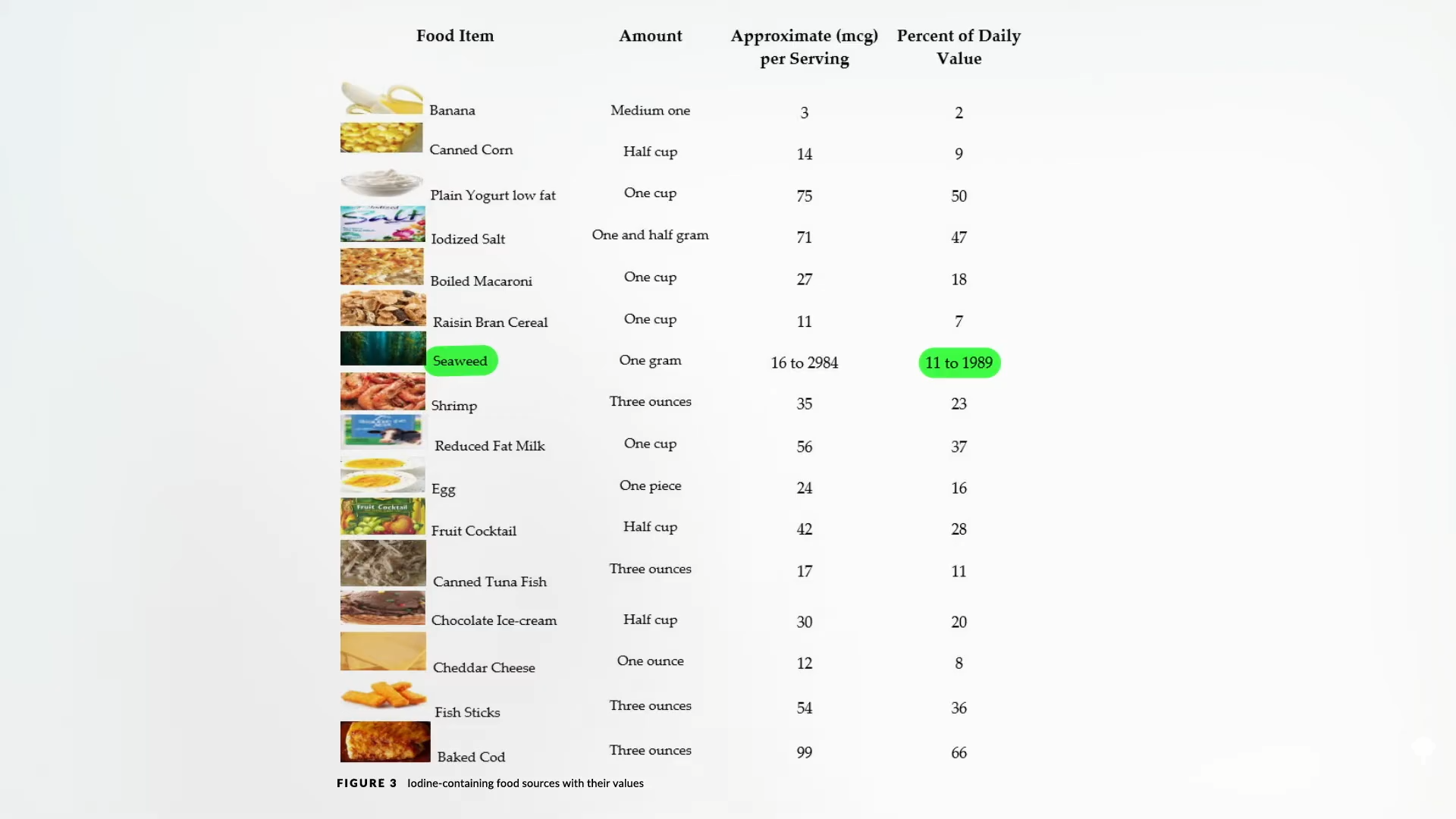

In that case, what’s the best source of iodine then? Sea vegetables, as you can see below and at 2:50. We can get a little iodine here and there from a whole variety of foods, but the most concentrated source by far is seaweed. We can get up to nearly 2,000 percent of our daily allowance in just a single gram, about the weight of a paperclip.

“Given that iodine is extensively stored in the thyroid, it can safely be consumed intermittently,” meaning we don’t have to get it every day, “which makes seaweed use in a range of foods attractive and occasional seaweed intake enough to ensure iodine sufficiency.” However, some seaweed has overly high iodine content, like kelp, and should be used with caution. Too much iodine can cause hyperthyroidism, a hyperactive thyroid gland. A woman presented with a racing heartbeat, insomnia, anxiety, and weight loss, thanks to taking just two tablets containing kelp a day.

In my last video, I noted how the average urinary iodine level of vegans was less than the ideal levels, but there was one kelp-eating vegan with a urinary concentration over 9,000 mcg/liter. Adequate intake is when you’re peeing out 100 to 199 mcg/liter, and excessive iodine intake is when you break 300 mcg/liter. Clearly, 9,437 mcg/liter is way too much.

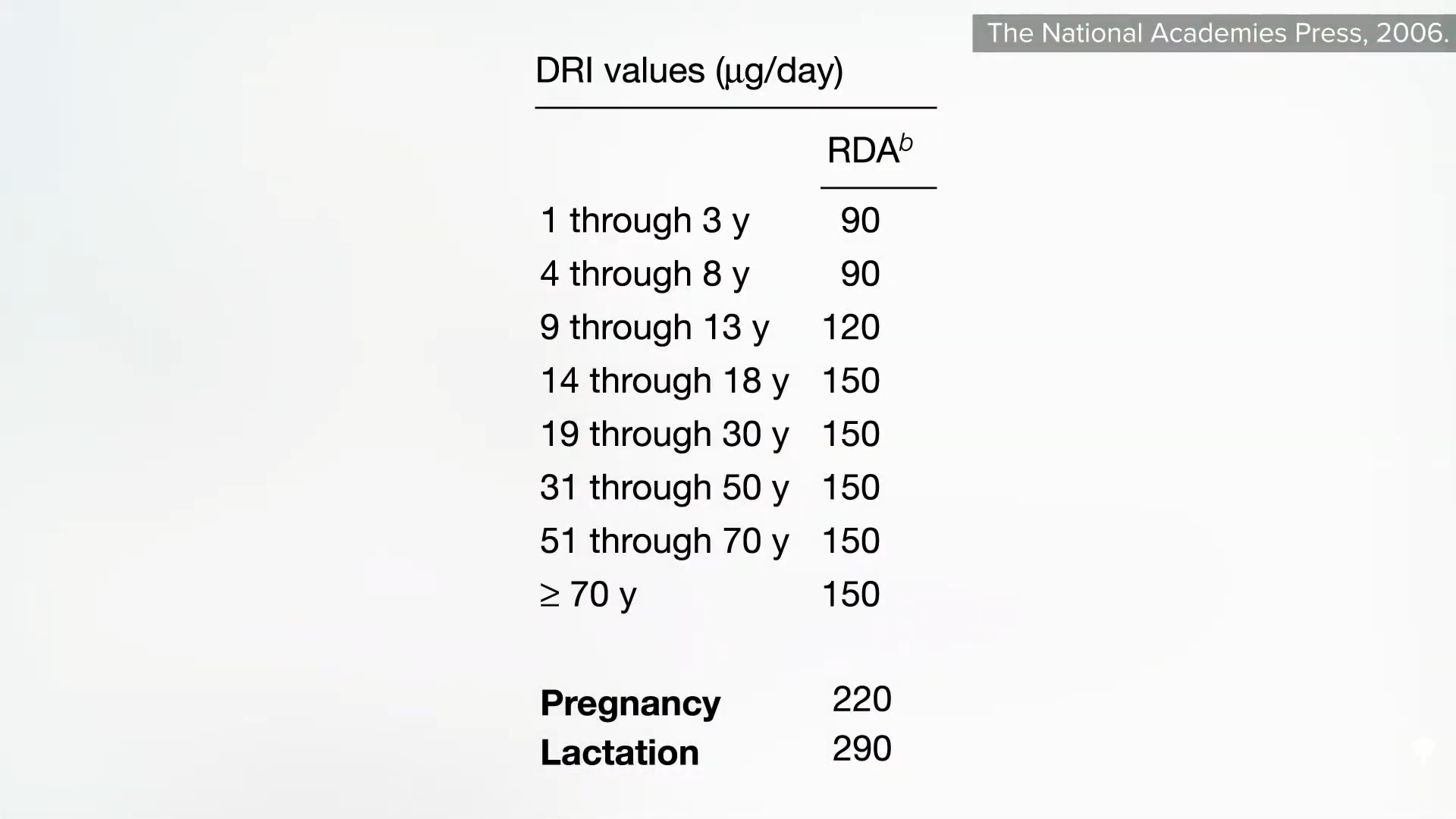

As you can see below and at 3:57 in my video, the recommended average daily intake is 150 mcg per day for non-pregnant, non-breastfeeding adults, and we may want to stay below 600 mcg a day on a day-to-day basis, but a tablespoon of kelp may contain about 2,000 mcg. So, I’d stay away from kelp because it has too much iodine, and I’d also stay away from hijiki because it contains too much arsenic.

This can give you an approximate daily allowance of iodine from some common seaweed preparations: two nori sheets, which you can just nibble on them as snacks like I do; one teaspoon of dulse flakes, which you can just sprinkle on anything; one teaspoon of dried arame, which is great to add to soups; or one tablespoon of seaweed salad.

If iodine is concentrated in marine foods, “this raises the question of how early hominins living in continental areas could have met their iodine requirements.” What do bonobos do? They’re perhaps our closest relatives. During swamp visits, they all forage for aquatic herbs.

Doctor’s Note:

This is the second in a four-video series on thyroid function. If you missed the previous one, check out Are Vegans at Risk for Iodine Deficiency?.

Coming up are The Best Diet for Hypothyroidism and Hyperthyroidism and Diet for Hypothyroidism: A Natural Treatment for Hashimoto’s Disease.

What else can seaweed do? See the related posts below.