Failure is a big topic in the weight lifting world these days. When you’re doing an exercise, do you need to push each set to the point that you literally can’t complete one more rep? Old-school practical wisdom says yes. More recent scientific studies have suggested that training to failure isn’t necessary, and might actually be counterproductive because it takes such a big toll on both your muscles and your mind.

The truth is probably somewhere in the middle, according to a new study in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise—but the results lean toward the idea that failure isn’t necessary for most of us. The study finds that getting close to failure produces strength gains that are similar to going all the way. That said, training to failure does build a little more muscle mass at some locations. The results of the study also offer some useful clues for those of us seeking the biggest muscle gains from the least amount of time and effort in the gym—not because we’re lazy, I hasten to add, but because we want to spend that time and effort in other ways.

Brad Schoenfeld and his colleagues at City University of New York (CUNY) Lehman College put 42 participants—34 men and 8 women—through an eight-week full-body training program. One group was assigned to complete all their sets to failure while the other was instructed to always stop short of failure. The volunteers were all experienced lifters who had been hitting the gym at least three times a week for more than a year, which means there were no easy gains to be had. And the experimental lifting protocol called for just two workouts a week, with each workout consisting of just one set of nine different exercises. In total, each workout took about half an hour.

This idea of short, single-set workouts isn’t radical or new. Back in the 1970s, Arthur Jones, the inventor of Nautilus exercise machines, popularized an approach that relied exclusively on single sets to failure. The problem is that pushing to true failure is no joke. It takes a lot of mental focus, and it also takes more time to recover. If your primary interest is another sport like running, you don’t necessarily want your legs to feel like lead the day after a strength workout. So it would be nice if it were possible to get most of the benefits of a hard workout while stopping short of true failure.

To test that theory, the approach Schoenfeld and his colleagues used is called “repetitions in reserve.” The subjects in the non-failure group were instructed to continue each set until they felt they had two repetitions in reserve, meaning that they would be able to squeeze out two more complete reps before failing on the subsequent one. It seems like a much more humane way to train—and it also turned out to be fairly effective.

The most surprising result of the study is that both groups got measurably bigger and stronger even though they were working out less often than they were before the study period. That fits with a bunch of previous research on the “minimum effective dose” for strength training. It doesn’t mean that half an hour, twice a week is sufficient to maximize your gains. But it does mean that those of us for whom strength training is mostly a means to some other end (like staying healthy, avoiding injury, or being able to carry a heavy pack) can make progress with a relatively modest investment of time.

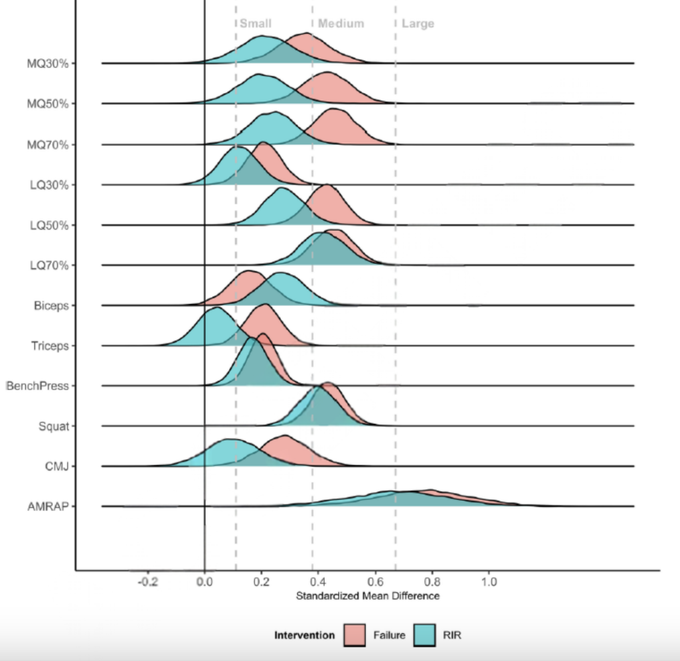

As far as the efficacy of training to failure goes, there were a whole bunch of different outcomes in the study. The simplest were one-rep max in the bench press and squat, as measures of upper and lower body strength. To test explosive power, the researchers used a countermovement jump (CMJ), which simply involves squatting down then leaping as high as possible in a single motion. To test muscular endurance, they had the subjects complete as many reps as possible (AMRAP) on a leg-extension machine lifting 60 percent of their body weight.

The four tests of strength (bench press, squat, CMJ, and AMRAP) are at the bottom. The solid vertical line at 0.0 corresponds to no change after eight weeks of training. Both bench press and squat increased, with no significant difference between groups. For example, max squat increased by 13.2 percent on average in the failure group and 12.4 percent in the reps-in-reserve group. Same with muscular endurance (AMRAP). Power (CMJ), on the other hand, increased more in the group that trained to failure.

The picture was different for muscle size, which is shown in the upper part of the graph above. Researchers used ultrasound to measure various points along the mid and lateral quadriceps (MQ and LQ on the graph) as well as the biceps and triceps. In most (but not all) cases, training to failure produced bigger gains in mass—which might be ideal if you’re working out for aesthetic reasons, but not necessarily if you’re training for a weight-to-strength ratio sport like cycling or climbing.

There’s a key caveat here, which is that estimating reps in reserve is an inexact art. To check how inexact it was, the researchers sometimes asked their subjects to keep going after they’d estimated they had two reps left. The estimates were fairly good and got better over the course of the eight-week study. But these were experienced lifters who had presumably experienced true failure many times before. For newbies, Schoenfeld says, it’s probably a good idea to do at least some training to failure so that you know what it feels like. Then, once you have a good internal benchmark, switch to a reps-in-reserve approach.

In some ways, this line of research reminds me of the current debate in the endurance world about Norwegian double-threshold training. The underlying premise of the Norwegian method is that hero workouts that leave you crumpled by the side of the track are counterproductive. Better to push hard enough to stimulate adaptation but not so hard that you can’t recover for the next workout. Those who hope to win bodybuilding competitions will undoubtedly—and wisely—keep lifting to failure. On the other hand, for those who want muscle and strength but care more deeply about tomorrow’s run, keeping a rep or two in reserve sounds like a great plan.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.

The post Can You Get the Same Gains Without Lifting to Failure? appeared first on Outside Online.