Sungida Rashid had no intention of taking an Uber to the birth of her first child. She’d never been one to take the easy route, and besides, she wanted to get things moving—and walking seemed the best way to do it. So on an overcast Sunday in October 2023, Sungida and her husband, Nabil Haque, set out from their Boston apartment to St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, the local hospital where Sungida, nine months pregnant, was scheduled to be induced.

Sungida and Nabil had met 12 years earlier while working at a consulting firm in their native Bangladesh. Over lunches, they began strategizing about PhD applications, eventually spending years in a long-distance relationship as they fell in love and pursued their doctoral degrees in the United States. Then there was a tiny pandemic wedding, a move to Bangkok for work (she was an economics professor, he a climate researcher), a heartbreaking miscarriage, the cautious joy of another pregnancy, and finally, when Sungida was seven months along, a job opportunity for Nabil at Boston University.

Sungida had waved off her husband’s suggestion that they delay his start date so she could stick with her doctors in Bangkok. She’d long dreamed of teaching at an American university, and the pandemic had upended several job prospects. Living in Boston would give her the chance to pursue a professorship again and, more importantly, to raise their little girl far from Bangladesh, in a country that offered greater opportunities, cleaner air, and better medical care.

In their first days in Boston, Nabil set up appointments at two prospective hospitals: Brigham and Women’s, a world-renowned nonprofit medical center, and St. Elizabeth’s, a humbler facility owned by a national for-profit hospital chain called Steward Health Care. The appointment at St. Elizabeth’s came first, and Sungida liked the midwife, so they canceled the other appointment. A few weeks later, they walked in and got ready for her induction.

Her labor moved slowly, but at around 1 a.m. on October 17, Sungida gave birth to a healthy baby girl. She and Nabil named her Otindria—Bangladeshi for “extra sensory”—and snapped a smiling selfie as a new family of three, Otindria snuggled in a hospital swaddle.

In the hours after, Sungida experienced some excess bleeding that doctors resolved, and soon she and Nabil moved to the recovery floor. With Otindria in her bassinet and Sungida in bed, Nabil coordinated video calls with family. He kept trying, and failing, to swaddle the baby in her blanket—he and Sungida laughed at how easy the nurses made it look. She reassured him they would get the hang of it.

In the afternoon, Nabil made a quick trip back to their apartment. When he returned, he told Sungida he already missed his newborn daughter. “Oh, you don’t miss me now?” she joked. She was having some back pain, and nurses brought in ice packs and heating pads for relief. But as the couple settled in to watch The Avengers—Sungida was a huge Marvel fan—her pain worsened.

After about 10 minutes, staff came in to check her vitals. Her blood pressure had dropped dangerously low. Alarms began to sound: “Code red on the recovery floor!” a voice blared over the loudspeaker. What felt to Nabil like 20 people rushed into their room. They wheeled Sungida out and took Otindria to the nursery.

Nabil sat in the recovery room alone—no bed, no baby. Every so often, someone came by with an update. A CT scan showed Sungida’s abdomen had filled with blood; she needed surgery. In the OR, doctors discovered the bleed was coming from her liver. They told Nabil they would insert an embolism coil—a small device that can be placed in blood vessels to stem internal bleeding. About half an hour later, hospital staff informed Nabil they needed to transfer his wife to Boston Medical Center, 20 minutes away, because it was better equipped to do the procedure, they said.

What no one told him was that St. Elizabeth’s supply of embolism coils had been repossessed by the vendor a month earlier. According to a complaint later filed with the state health department, the hospital owed more than $500,000 for these devices; the vendor claimed in a lawsuit that, nationally, Steward facilities owed it nearly $5 million. A group of St. Elizabeth’s nurses had confronted Steward management about this at a tense union meeting three weeks prior: What if a patient needed a coil? The irritated chief nursing officer responded that the hospital simply wouldn’t accept transfer patients with internal bleeding. But what if something happened in-house? The CNO didn’t answer the question.

Now that exact scenario was unfolding, and staff had little choice but to transfer a woman in the midst of surgery. A nurse whisked Nabil upstairs to watch as Sungida, lying on a stretcher, her face pale, tubes up her nose, was wheeled down a hallway and out to a waiting ambulance. It would be the last time he saw her alive.

St. Elizabeth’s was just a sliver of Steward’s empire. At its peak, the company boasted 41 hospitals in 10 states, medical facilities in four foreign countries, and roughly $8 billion in annual revenue. It distinguished itself to investors by promising a way to tackle a thorny problem for the industry: how to run hospitals in low-income communities while still turning a profit.

Industry dominance was always the dream of Steward’s CEO, Ralph de la Torre. When he took the helm of a struggling Massachusetts-based Catholic hospital chain called Caritas Christi in 2008, de la Torre—a child of Cuban immigrants and famously ambitious cardiac surgeon—was so sure of succeeding that he let his medical license expire. Two years later, he convinced the powerful private equity firm Cerberus Capital Management to buy Caritas, which it renamed Steward. His timing was perfect: Private equity firms, which focus on generating a big, quick payday for their investors, had just begun ramping up their positions in health care. De la Torre hoped that teaming up with Wall Street would catapult him to national prominence, kicking off what the Boston Globe called “a royal conquest.”

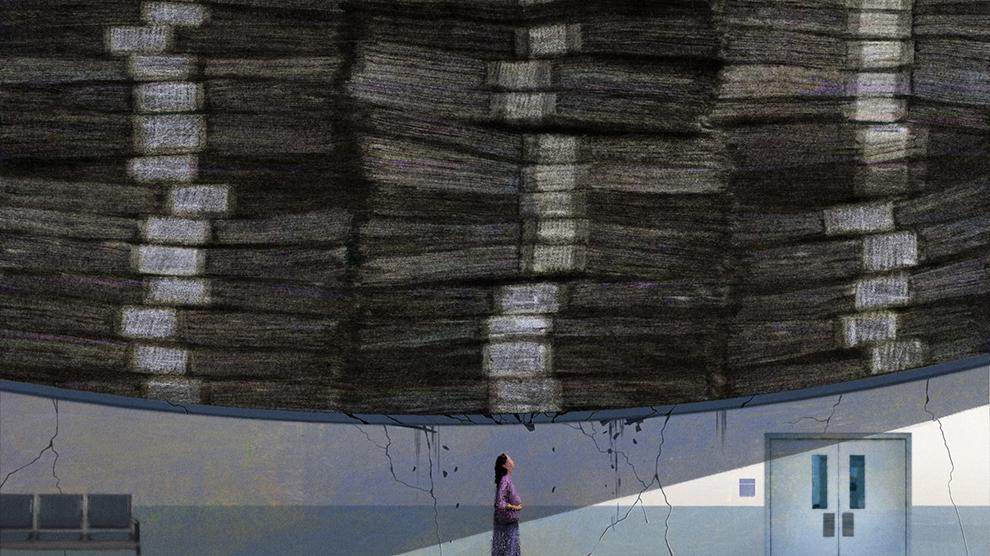

His reign came to an end when Steward filed for bankruptcy in May 2024, a spectacular downfall helped along by Cerberus and Medical Properties Trust (MPT), a mysterious Alabama-based real estate investment trust that became heavily involved in the company over the last decade. Steward has since been the subject of news reports and Senate hearings trying to grasp the astonishing scale of its unpaid bills—$9 billion owed to more than 100,000 creditors—and the extent to which patients suffered as executives enriched themselves.

De la Torre, for instance, bought himself a $40 million yacht and an $8 million apartment in Madrid, made hundreds of trips on Steward’s private plane, and gave $10 million to his children’s elite prep school in Dallas, a donation financed partially from Steward’s coffers, according to leaked documents obtained by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. Cerberus made $800 million, more than tripling its investment. The CEO of MPT earned nearly $18 million last year, making him the highest-paid executive in Alabama. (De la Torre did not respond to a request for comment. Cerberus and MPT declined to answer questions from Mother Jones. In public documents, both companies have denied that their actions contributed to Steward’s financial distress.)

It was Sungida’s death that first connected this excess to its human costs. A January 2024 Globe story lit a fire under Massachusetts officials and regulators, who expressed outrage that profit motive had trumped patient care in a city that prides itself on world-class hospitals. Sen. Ed Markey convened a hearing that opened with a reference to Sungida, while Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who for years has fought to rein in Wall Street, warned that Steward was no outlier. “I will say it bluntly,” she said. “Turning private equity loose in our health care system kills people.”

I’ve heard this repeatedly while writing about private equity over the last five years. One study found that private equity–owned nursing homes had a mortality rate 10 percent higher than their non-PE counterparts; another noted that patients at PE-owned hospitals are 25 percent more likely to suffer an unrelated injury while admitted, whether a fall or an infection. But such studies only provide a glimpse of the problem. As savvy executives squeeze returns out of facilities that determine whether patients live or die, there is no systematic data tracking how their acquisitions affect care. Before its downfall, Steward was among private equity’s biggest health care conquests. I wanted to know how many more Sungidas were out there.

“The reason that there are more cases with Steward is not because they have worse doctors. It’s that they didn’t give the doctors and nurses and all the staff the resources they need to do their job the right way.”

Over the course of our yearlong investigation, Mother Jones reviewed every malpractice, personal injury, and wrongful death case filed in state and federal courts involving Steward hospitals. We found 469 lawsuits involving 83 patient deaths; many have settled or have been thwarted by Steward’s bankruptcy, while some were dismissed or resolved in the company’s favor. These numbers may understate the extent of the problem, given that the company’s hospitals served primarily low-income communities, where most patients and their families lack the resources to mount a case. We also combed through Steward’s federal inspection reports, finding 708 “deficiencies” in patient care, including 35 classified as “immediate jeopardy”—situations that led or could lead to serious harm or injury. Although it is difficult to pinpoint the degree to which Steward’s business choices contributed to poor treatment, academic research has shown that systemic issues, not individual errors, typically lie at the root of malpractice.

Steward’s bankruptcy paused many of the malpractice suits, making it difficult or impossible for attorneys to depose medical staff or obtain company records—information that could link their allegations of malpractice to cost-cutting decisions. But what is clear, experts say, is that a pattern of substandard care arose as Steward and its partners prioritized their bottom lines. (Steward declined to answer detailed questions from Mother Jones.)

“Steward made a decision somewhere along the line that in order to keep making the money they wanted to make, there were going to have to be cuts,” says Rob Higgins, a partner at the Boston malpractice firm Lubin & Meyer who has litigated dozens of cases against Steward hospitals. “The reason that there are more cases with Steward is not because they have worse doctors. It’s that they didn’t give the doctors and nurses and all the staff the resources they need to do their job the right way.”

Our reporting builds on the work of other journalists and legislators who have investigated Steward’s activities. The Globe’s Spotlight team found at least 15 patients who died at Steward facilities after receiving subpar care. A Senate report from September found that heart-failure death rates at some hospitals increased by up to 40 percent on Steward’s watch, even as the national average declined. Wait times in Steward ERs were also far above the national average.

Our investigation also dug up allegations of sexual assault by medical staff, lawsuits by whistleblowers who alleged they were fired for calling out Steward management, and a troubling pattern of problems in labor and delivery: We found 12 additional instances of moms and newborns who died at Steward hospitals over the last 14 years, and 21 more who suffered severe injuries. From skipped ultrasounds to inexplicable delays in emergency care, the court filings recount gutting details.

One Florida woman lost her baby after waiting almost three hours for someone to perform a C-section, despite a placental abruption, excessive bleeding, and dramatic drops in the fetal heart rate; it was her ninth pregnancy and the first she’d carried to term after years of IVF. At another Steward hospital in Florida, doctors wanted to prescribe a steroid drug to treat a woman’s postpartum blood disorder, but no administrators were reachable over Labor Day weekend to approve the order, and she died. At St. Elizabeth’s, where Sungida went, another patient bled so much after giving birth that she suffered a stroke and needed brain surgery—in part because an ultrasound to assess the hemorrhage was done too late. At a Steward facility in Texas, a baby was born with severe brain injuries after staff waited almost a day to perform a C-section, despite clear signs of fetal distress. There are more cases like these: 49 of Steward’s federal deficiency reports involve maternal care.

The labor and delivery problems at Steward hospitals are consistent with an industry cost-cutting trend: When private equity firms and other financiers buy hospitals, they tend to target obstetrics units. “There is a mismatch between how much obstetrics costs and how much revenue it generates,” explains Katy Kozhimannil, a health policy professor at the University of Minnesota who studies maternal unit closures. Insurance reimbursement rates for maternal services are notoriously low, and the costs of running a fully staffed unit—with specialized doctors, nurses, anesthesiologists, and birthing equipment—can quickly outpace returns.

As the allegations of deadly neglect swirl around Steward, its investors, executives, and partners have faced little accountability.

Many hospitals eat the loss, Kozhimannil says, because maternity services fulfill a community need and align with their public mission. But investor-owned hospitals, unwilling to make that trade-off, have been closing maternity wards for years. Ascension, a Catholic hospital chain that partnered with the private equity firm TowerBrook Capital Partners, has closed more than a quarter of the labor and delivery units at its 140-plus hospitals over the last decade. Prospect Medical Holdings shuttered one of the few obstetrics units in its 16-hospital system after it was taken over by the private equity firm Leonard Green & Partners. Steward closed at least six labor units and two neonatal units, as well as three hospitals that provided obstetric services—eliminating a third of the labor units in its portfolio.

As the allegations of deadly neglect swirl around Steward, its investors, executives, and partners have faced little accountability. Senators held de la Torre in criminal contempt after he refused to testify at a hearing in September, yet officials from Cerberus and MPT, the real estate investment trust, weren’t even summoned, despite their involvement in Steward’s unraveling.

A number of financial analysts have published evidence showing how MPT, which still owns the real estate of dozens of Steward hospitals, used those properties in its own enrichment scheme. MPT has gone to extremes to quash the findings, paying millions of dollars to private intelligence firms to target Steward’s critics, filing a defamation lawsuit, and subpoenaing those who dare speak to the press.

The broader Steward saga is stunning in its complexity, brazenness, and scale, laying bare the extent to which profit-seeking and patient care are incompatible, and the lengths to which corporate titans have gone to hide that reality. “All of a sudden, somewhere, there’s a switch that turns that says, maybe we can make a boatload of money,” Higgins says. “They were living a lifestyle of NBA basketball players that have hundreds of millions of dollars. And it’s scary to think that for a long period of time, they were running these hospitals the way they were.”

Nabil got to Boston Medical around midnight. He was ushered into an empty waiting room and told to make himself comfortable: His wife’s surgery would be long. He called his parents and made plans for them to fly to Boston to help during what surely would be a difficult recovery.

Barely an hour later, a surgeon appeared. They had tried everything, but the bleeding was too severe. There was just too much damage to her liver. Sungida was dead. “How?” Nabil asked in disbelief. “We don’t know,” the doctor said. He told Nabil he could request an autopsy.

“I will say it bluntly. Turning private equity loose in our health care system kills people.”

Nabil sat in the waiting room, stunned. Just hours ago, he and Sungida had been talking about watching a movie together. Now he was texting relatives with the unspeakable news. He was eventually led through a maze of hallways and into a basement room where a staffer pulled back a curtain and revealed his wife’s body, covered with a sheet. “It was so scary seeing her lifeless,” he says. “I couldn’t stand there for more than five minutes.”

Someone called him an Uber. When he got back to his apartment at 4 a.m., Nabil saw Sungida everywhere: in her beloved saris and half-used perfume bottles and the suitcase of pre-pregnancy clothes she hadn’t yet unpacked because none of them fit. He opened the fridge to find the food she’d prepared for their first days as a family of three. “I was still in shock,” he recalls. “I didn’t know what to do.” His mind turned to his daughter, and to their unfathomable future: “She was so tiny and so fragile—how is she going to survive this?”

When Nabil called the nursery to check on Otindria, the nurses said she was doing fine. They asked after Sungida—they hadn’t yet heard. After the call ended, the nurses texted him photos of the baby. He couldn’t believe how much she already looked like her mother. For the rest of his life, he realized, it would be his job to convince Otindria that what happened wasn’t her fault. He climbed into the shower and, for the first time, allowed himself to cry.

Later, he sat down and wrote a Facebook post: “Yesterday, I welcomed my daughter to this world,” it began. “Today, I am in grief losing the mother of my daughter due to unexplained medical circumstances.” He asked their friends to reminisce about Sungida and to refrain from asking medical questions. Her doctors were “bewildered,” he wrote.

After a few hours of sleep, he headed back to St. Elizabeth’s to check on Otindria and attend a briefing with hospital staff. It was held just a few doors down from the recovery room where Sungida had so recently been alive, alert, and cracking jokes.

Doctors and administrators crowded into the cramped room. As Nabil held his newborn, they told him that this was a freak event. They hypothesized that the hormonal roller coaster of labor and birth had caused a blood vessel in Sungida’s liver to burst. Maybe, they said, something about her liver was anatomically different. There was no mention of the repossessed coils, of the tense union meeting, or of the management’s failure to plan for this very scenario. Nabil remembers them saying repeatedly that his wife’s death was improbable and random: “They said, ‘You can think of it like your wife got hit by lightning.’”

He had only one question, the one gnawing at him since the night before. Would Otindria blame herself? One of the doctors answered immediately: If she ever does, he should tell her it was the hospital’s fault.

Steward’s rise and fall is a telling example of how the private equity playbook has infiltrated American life. Over the last two decades, PE firms, which invest money on behalf of wealthy clients and major investors like pension funds, have been buying up everything from family homes and apartment buildings to day cares and medical practices and transforming them into bundles of assets to be engineered for profit. They charge investors hefty management fees and, in exchange, promise market-beating returns in just a few years. To do that, they focus on cutting costs—scrimping on wages, benefits, and materials—to extract maximal returns.

When President Barack Obama signed the Affordable Care Act in 2010, he unwittingly opened up a fresh prospect for private equity. The droves of newly insured Americans, the industry suspected, would mean a big revenue boost for hospitals. Community hospitals presented a particularly attractive option because Medicaid expansion meant more patients at higher reimbursement rates, and the government would likely bail out facilities that failed. Soon private equity firms were snapping up hospitals like never before.

That same year, Cerberus—named for the three-headed dog who guards Hades in Greek mythology—bought six hospitals from de la Torre’s small Catholic hospital chain, Caritas, for $895 million. It put up one-third of the total in cash, and, as is common in private equity deals, financed the rest with loans loaded onto Steward’s balance sheet.

Turning a nonprofit into a for-profit required approval from Massachusetts’ attorney general, which she granted on condition that Cerberus invest $400 million in hospital upgrades. Cerberus complied, but covered the cost by saddling Steward with even more debt—loans that Cerberus and its investors would not be responsible for repaying.

De la Torre, now Steward’s CEO, introduced himself soon after to the staff of one of the newly acquired hospitals. To a packed auditorium, he recalled learning to scuba dive as a kid and how he’d been taught you should always go with a partner. If you encounter a shark, he joked, you grab your diving knife, stab your partner, and swim away. “He was expecting a big laugh,” one staffer who attended the speech recalls. “But what he got was gasps.”

Cerberus rapidly acquired five more Massachusetts hospitals, adding more debt to Steward’s ledger. By 2012, Steward was a $1.9 billion company with 17,000 employees, and it wasn’t long before executives’ cost-cutting efforts began drawing their ire. After the company eliminated more than 100 nursing jobs in two years, the nurses union filed more than 1,000 complaints with the state health department alleging unsafe staffing.

Although Steward’s hospital portfolio was then limited to roughly a dozen facilities, it soon closed one of them and shut down pediatrics at another. It also began selling some of its buildings and renting them back. These “sale-leasebacks” provided a cash infusion to offset Steward’s growing debt load, which would triple during Cerberus’ first four years of ownership.

In mid-2015, de la Torre flew to Alabama to meet with Edward Aldag, the unofficial king of health care sale-leasebacks. A dozen years earlier, Aldag had founded Medical Properties Trust, a one-of-a-kind real estate investment trust (REIT) that focused exclusively on doing such deals with hospitals. The men decided on the spot to work together: MPT’s annual report described them bonding over their “similar philosophies” about the future of health care.

All involved had something to gain: Cerberus and de la Torre wanted to expand Steward, and an MPT deal would give them the cash to do it. MPT said in its annual report that it would collect rent from Steward hospitals and would have the option to buy any new facilities Steward acquired—to transform them, too, into lucrative tenants.

“It’s just this long line of rinse and repeat of basically looting safety-net hospital systems.”

By 2016, MPT had bought Steward’s nine remaining Massachusetts hospitals for $1.25 billion and leased them back at exorbitant rents. If the aim was to provide quality care, one of de la Torre’s colleagues told the Globe, this made no sense: “We all sort of nodded our heads and rolled our eyes and said, ‘Oh, now I get it. There are no plans to turn this into a viable set of community hospitals. It’s all about pulling money.’”

Cerberus used proceeds from the sale to pay itself more than $700 million—a $473 million return on investment. De la Torre received a $71 million dividend. Over the next three years, Cerberus used the remaining funds to finance the purchase of 26 more hospitals in nine states, piling even more debt on Steward, whose facilities continued to face cuts. Patient care fiascoes were starting to escalate. At Good Samaritan Medical Center in 2018, a baby died when her mother’s uterus burst, according to legal filings—overworked staff had ignored her history of placental abruption. In fact, in the years after MPT first got involved, at least 20 patients died at Steward’s Massachusetts hospitals from alleged malpractice; 50 more died at its other facilities across the country during that time, according to the complaints we found. (Some of these cases were dismissed or settled; others remain open due to Steward’s bankruptcy.)

In a region full of Harvard-affiliated doctors and hospitals known for being among the nation’s best, Steward’s raw Wall Street calculus was so foreign that it went virtually undetected, says Dr. Paul Hattis, a senior fellow at the Lown Institute, a health care think tank, who has served on the state’s Health Policy Commission. “I don’t think the regulatory apparatus was used to dealing with actors fueled by that kind of greed,” he says. “The money was going into the organization and then out the back door into the dividend pocket of an owner, but then neglecting patient care in the middle. That just was not something that we were used to thinking about having to protect against—the bleeding of an asset. So, you say, ‘Why didn’t regulators do more?’ I think they didn’t fully grasp what was going on until it was too late.”

After Sungida’s death, Nabil’s parents, brother, and sister-in-law flew in to help. They shared his small bedroom while Nabil slept on the chaise in the living room, Otindria in her bassinet beside him.

Every day delivered another gut punch. On Sungida’s phone, Nabil discovered a note she had written to introduce her baby to the world. He opened her inbox to find an interview offer for an economics professorship at Central Michigan University. “Seeing that email, I was like, You got everything you wanted,” he recalls. “It broke my heart.”

About a month later, he got an email from a reporter at the Globe. Nurses at St. Elizabeth’s and their union had filed a complaint with the state department of health over the repossession of the embolism coils and what had happened to Sungida. He sat in his office at Boston University, unsure of what to think. He felt lost, even skeptical, but also distraught. Could this coil have saved her? Then he got a bill for the cost of her medevac to Boston Medical.

Given what Nabil now knew about the coil, he wondered whether he was being asked to pay $1,076 for transport that should never have been necessary. His anger intensified when he received Sungida’s autopsy report from Boston Medical. It said she’d had placenta accreta, a condition that usually needs to be resolved by removing the uterus after birth. If true, that meant St. Elizabeth’s had missed it—yet another glaring shortfall, he thought, in Sungida’s care. He emailed the hospital’s chief medical officer, who in a subsequent briefing disputed the autopsy findings, insisting that there was no placenta accreta—and that her liver was the only problem.

Sometimes, at night, he would hold Otindria close and whisper into the darkness: “Your childhood would be so different if it was the other parent.”

Back home with Otindria, Nabil settled into a routine he repeated every three hours: feeding, fresh diaper, back to sleep. Scrolling Netflix one night, he came across the movie Fatherhood, which follows a dad (Kevin Hart) whose wife dies in a Boston hospital after giving birth to their daughter. The parallels felt uncanny. Hart’s character wrestles with whether to move home to the Midwest, where his mother can help care for the baby. Nabil faced the same dilemma. Sungida’s greatest hope had been for her girl to grow into an independent woman in a place where she would face fewer limits. But he was overwhelmed by the thought of caring for Otindria alone.

He decided to go back to Dhaka. As he planned the move, Nabil thought often about how Sungida would have handled the situation so much better. She would have figured out a way to keep Otindria in America and put up a stronger fight to find out what had happened at the hospital. Sometimes, at night, he would hold Otindria close and whisper into the darkness: “Your childhood would be so different if it was the other parent.”

If she had to lose a parent, he thought to himself, it should have been him.

In the years before Sungida’s death, MPT acquired one Steward hospital after another, binding each facility to a high-rent lease. Steward began to cut costs even more aggressively. In 2017, it closed the maternity ward at a hospital in southeastern Massachusetts. The next year, it shut down Northside Regional Medical Center in Youngstown, Ohio, which housed the city’s only labor and delivery unit. In 2019, it closed its hospital in Phoenix and a neonatal unit in Easton, Pennsylvania. When the pandemic hit, it threatened to shutter the Easton facility altogether, demanding $40 million from the state to stay open—the governor granted $8 million. Steward took the money, closed the obstetrics unit, and sold the hospital three months later for $15 million.

Steward’s other hospitals deteriorated, according to government proceedings. Janitors at its Haverhill, Massachusetts, facility were buying toilet paper for patients with their own money. At St. Elizabeth’s, nurses purchased specialized bereavement boxes for stillborn babies after the hospital ran out. In West Monroe, Louisiana, a nurse practitioner discovered that Steward had stopped paying its on-call cardiologist as the doctor was caring for a patient in the middle of a heart attack.

The company seemed to be bleeding money: It reported losses of $207 million in 2017 and $271 million in 2018. During the pandemic, Steward claimed its largest loss ever—$408 million—despite record levels of government assistance.

The company also faced a criminal inquiry in Malta, tied to a $4.35 billion contract it had won to operate three government hospitals in the island nation. Millions in taxpayer funds earmarked for improving the facilities seemed to disappear; Maltese officials sued Steward, accusing it of using the money for bribes and kickbacks and to “unjustly enrich itself.” (Their investigation is ongoing.)

In some years, Steward hospitals made up more than a third of MPT’s assets and almost half of its revenue. If Steward died, it could take MPT with it.

By the end of 2019, Cerberus executives began expressing concern to investors. Then, in May 2020, they engineered a complex transaction that transferred the firm’s $350 million stake in Steward to de la Torre and other Steward leaders as a loan, giving them five years to pay it back. Experts wondered whether this hinted at an impending collapse: In bankruptcy proceedings, lenders tend to get paid whereas stockholders don’t. (Cerberus has denied that this was its motivation.)

MPT, too, was thinking about how to protect its bottom line. For the real estate trust, Steward’s survival was existential. In some years, its hospitals made up more than a third of MPT’s assets and almost half of its revenue. If Steward died, it could take MPT with it.

Its solution was a top-secret plan executives dubbed “Project Easter,” according to internal documents obtained by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. Publicly, MPT expressed optimism. In an early 2021 earnings call, CEO Aldag bragged that the company “has the strongest portfolio of hospitals in the world.” But privately, according to the OCCRP’s documents, MPT executives knew Steward was desperate for cash, so they devised a scheme that would keep it afloat while enriching executives of all three companies.

In the summer of 2020, MPT purchased several Steward properties, pouring $400 million into the company. Six months later, it loaned Steward $335 million to help buy out Cerberus’ stake, bringing the private equity firm’s total profit from its ownership of Steward to $800 million. That same month, Steward paid its investors $111 million, which included about $83 million for de la Torre; MPT, which owned almost 10 percent of Steward, pocketed a cool $11 million.

When MPT disclosed the deal in federal filings four months later, the financial press took notice. Not only was the deal “unusual,” per Bloomberg, but it revealed a growing private equity pattern, wherein a sort of Russian nesting doll of financiers work together to make money off struggling hospitals.

After the Wall Street Journal and others wrote about the deal, Rob Simone, an investment analyst in suburban Connecticut, began seeing a surge of interest. Simone, 40, was a REIT specialist at Hedgeye, a research firm that does deep dives on stocks and sells them to portfolio managers. Suddenly, client after client was inquiring about MPT, which is publicly traded.

Poring over the firm’s financial filings, Simone began to suspect that MPT was propping up Steward well beyond the Cerberus deal, an arrangement he called “a perverse marriage” when we spoke last year. He started publishing research to this effect, and laying out the details on Hedgeye’s YouTube channel in his crisp, fast-talking style. MPT had announced, for example, that it was investing $169 million in a new Steward facility in Texas. A bit of Googling revealed that the project was slated for Texarkana, a small city on the state’s eastern edge. This piqued Simone’s interest: Texarkana’s population was shrinking, and it already had a perfectly good hospital. Developing a pricey new one made no sense.

By now, Simone knew MPT’s “special sauce” was buying up struggling safety-net hospitals, which are particularly vulnerable to the devil’s bargain of sale-leasebacks. Indeed, MPT’s high rents have cratered hospital systems in multiple states. Facilities can’t keep up, and they inevitably slash services or close down. Pipeline Health, for instance, declared bankruptcy in 2021, about a year after MPT bought its Los Angeles hospitals. A profitable community hospital in Watsonville, California, closed two years after MPT purchased it. “It’s just this long line of rinse and repeat of basically looting safety-net hospital systems,” Simone says.

It occurred to Simone: What if all this new investment was just a way of funneling cash back into MPT’s trail of failing hospitals?

MPT’s compensation scheme was also quite unusual for a REIT: Executive pay was tied to the dollar value of its acquisitions. The more hospitals MPT bought, and the more it paid for them, the more money the executives brought home. “You don’t just get compensated for paying the highest price, but also to go out and buy anything,” Simone says. “I knew right away when I saw that, this was going to be a bad outcome.”

After each hospital system faltered, MPT would buy a new one and issue a flurry of press releases. It occurred to Simone: What if all this new investment was just a way of funneling cash back into MPT’s trail of failing hospitals? Wasn’t this similar to a Ponzi scheme, in that MPT brought on new tenants who could afford to pay the rent to help prop up the older ones who couldn’t? (In a letter to senators, MPT denied the allegation that it is a Ponzi scheme.)

Simone hired a photographer to check out the Texarkana project. Financial statements said MPT and Steward were more than $50 million into the build, but the photographer sent back shots of an empty field. In one, a portable toilet lay toppled over. “$50 million was literally tumbleweeds,” Simone says. The photos further fueled his hunch that MPT was covering up Steward’s money problems by providing it cash that would come back to MPT as rent—payments MPT could then record as earnings to maintain a facade of business success. (In 2023, MPT commissioned an investigation that found no evidence of this.)

Simone published his Texarkana findings, affirming his earlier recommendation that his firm’s clients should short MPT—bet on the future decline of its stock. Soon after, he received anonymous death threats. Trolls on X went after him incessantly, even posting his home address and the country club to which he belongs.

But Simone’s reports motivated other analysts and short sellers to look into MPT. The most prominent was Viceroy Research, which had played a key role in exposing one of Europe’s greatest recent frauds—that of payment processor Wirecard, whose top executives now face criminal charges.

In 2023, Viceroy expanded on Simone’s findings, claiming that one of the ways MPT seemed to funnel money to Steward was by dramatically overvaluing its hospitals, according to legal filings. Viceroy calculated that MPT may have overpaid Steward by at least $1 billion for its real estate. For example, it loaned Steward $1.4 billion to buy a chain of 19 hospitals, but soon forgave $700 million of the loan. In another case, Steward bought a Texas hospital for $11.7 million and sold it to MPT the same day for $26 million. (MPT sued Viceroy and claimed its underwriting process for determining hospital values is accurate. The case was settled in December.)

There were other projects that seemed off. In 2021, Steward announced plans to build a state-of-the-art hospital in Utah, on a parcel of “trust land”—federally owned land bestowed to states to use for public benefit. To this day, the site remains an empty, overgrown field, yet another expensive project that may have existed only on paper. In 2022, Steward spent $60 million on a shuttered Miami hospital that it never reopened. (MPT did not respond to questions about its involvement in these hospital purchases.)

But no amount of financial contortion could stop Steward’s downward spiral. As the hospital closures continued, dozens of lawsuits from staff and stiffed vendors piled up, and the federal government sued the company, alleging Medicare fraud. In September 2023, a sales rep marched into St. Elizabeth’s to repossess the embolism coils that, three weeks later, might have saved Sungida’s life.

“I don’t think the regulatory apparatus was used to dealing with actors fueled by that kind of greed.”

Simone is a finance guy, and his research is aimed at helping investors. But as a father of three, he never lost sight of the likely human toll of MPT’s accounting tricks. Without MPT propping it up, he says, “Steward would have become a bankruptcy years ago.” About five years, he figures—five fewer years of “patients dying, hospitals closing, vendors not getting paid…everything would have been pulled forward in time and ended.”

In late January 2024, Nabil flew with Otindria to Bangladesh. Days later, the Globe published its story about Sungida’s death. It sparked a national reckoning. That’s “what finally blew the lid off all this,” a St. Elizabeth’s nurse told lawmakers at a subsequent Senate hearing.

That spring, Steward’s bankruptcy proceedings revealed more details about its looting of patient care: It owed nearly $300 million in unpaid wages, including more than $105 million to doctors and $42 million to a single nurse staffing agency. It owed almost $1 billion to various vendors, including $79 million to suppliers of care items ranging from sterilization equipment to newborn test kits.

Two Senate committees launched investigations into Steward and the broader trend of private equity in health care. Several states commenced their own accountability efforts—a blistering hearing in Louisiana, an investigation in Arizona, and a new law in Massachusetts that subjects private equity hospital owners to extra scrutiny and prevents them from selling hospital real estate to entities like MPT. Sen. Markey introduced a federal bill, though it has yet to move out of committee, that would regulate PE health care purchases.

As Steward fell apart, so did Nabil’s vision of his future. He and Sungida had relished the idea of parenting on their own—the “American struggle,” they’d called it. Now he was back with his parents, who spent hours each day caring for Otindria. It wasn’t the life he’d imagined.

He knows living in Dhaka has its benefits. His daughter will be adept in both Bangla and English. Her grandparents have become her best friends—each morning, Otindria drags her grandfather out on a walk to pet the neighborhood goat. But still, to Nabil, every day in Bangladesh feels like a small betrayal. “I didn’t want it to be her home, and her mother didn’t want it to be her home,” he told me. “That’s the broken promise that bothers me a lot.”

St. Elizabeth’s was briefly engulfed by another private equity giant, Apollo Global Management, before Massachusetts seized it through eminent domain.

He tries not to let it show. When I visited Dhaka in February, Otindria toddled through the apartment like a tiny queen, with Nabil as her cheerful attendant. He set up her Hello Kitty playpen in the living room, retrieved stuffed animals, and snuck her jalebi, a fried sweet, in between meals. Beneath the photos of Sungida that line most of the walls, he threw himself into playing with his daughter, never letting on that each parenting moment is tinged with sorrow. “I see Otindria doing everything Sungida would have wanted her to do,” he says. “But she’s not here to see it.”

Nabil has grown angrier at the system that upended his life. In the spring of 2024, he began discussions with a law firm about suing Steward. (He is now pursuing a case as part of the bankruptcy.) A few months later, de la Torre—Steward’s now-former CEO—was spotted at the Olympics in Paris, attending the equestrian dressage competition at Versailles. Federal agents briefly detained him this past fall, serving a search warrant and seizing his phone—potential signs of a federal probe. But as of this writing, neither he nor anyone else involved has been charged with a crime. MPT continues to do its business with Aldag at the helm—in January, another of its hospital chains, Prospect, declared bankruptcy. Stephen Feinberg, the billionaire co-CEO of Cerberus, was recently sworn in as the No. 2 at the Pentagon.

The 34 hospitals Steward owned when it declared bankruptcy are now in chaos. There have been hundreds of layoffs as new operators take control, and several closures. St. Elizabeth’s was briefly engulfed by another private equity giant, Apollo Global Management, before Massachusetts seized it through eminent domain and assigned ownership to Boston Medical Center—the same hospital system to which Sungida had been transferred.

In October, thousands of miles from this tempest, Otindria turned 1. Sungida and Nabil had agreed during her pregnancy that they wouldn’t host a blowout for their daughter’s first birthday—it felt silly when she wouldn’t care or remember. But Nabil’s parents insisted on a party.

Nabil usually rushes home from work to be with his daughter, but that night, he worked late on purpose: This birthday party felt like yet another detour from the couple’s plans, and he couldn’t stomach it—nor dissociate it from the worst day of his life.

When he thinks about the future now, everything revolves around Otindria. He daydreams about teaching her to drive one day, just as he taught Sungida when they were graduate students. He isn’t worried about his daughter making good grades or getting into a top college—things Sungida would have worried about. All he wants for her is joy. “Be a chef, go to a party school, travel,” he says. “Enjoy your world.”

Nabil no longer can say with any certainty that he and his daughter will leave Bangladesh when Otindria is older. He’d like to, but he’s loath to make any plans. “The future that I wanted imploded on me,” he says. “So now, I am scared to dream.”