The below article first appeared in David Corn’s newsletter, Our Land. The newsletter comes out twice a week (most of the time) and provides behind-the-scenes stories and articles about politics, media, and culture. Subscribing costs just $5 a month—but you can sign up for a free 30-day trial.

Imagine a situation in which the threat of fascism is so pressing that you consider sending your children to another country. That’s what happened decades ago for the family of Julian Borger, the world affairs editor of the Guardian. Borger has long been a keen observer of wars, global crises, and international relations. His work is an essential read for anyone looking to make sense of our mad world. But with a new book, Borger has cast his gaze back to the 1930s and a piece of family history he stumbled across only recently.

After Hitler annexed Austria in the Anschluss of March 1938, Borger’s grandparents and his father, Robert, then 11 years old, as well as all the families of the Jewish community of Vienna, became targets of the vicious antisemitic campaign waged by the Nazis and their Austrian allies. Soon after the Germans’ arrival, as the Borgers were being forced to give up their radio shop and subjected to hate, humiliation, and violence, they managed to find a way to send their only son to the United Kingdom. And, as Jews were being sent to labor camps, they, too, escaped Vienna.

This is quite the moment to be writing about Nazi authoritarianism and the Holocaust.

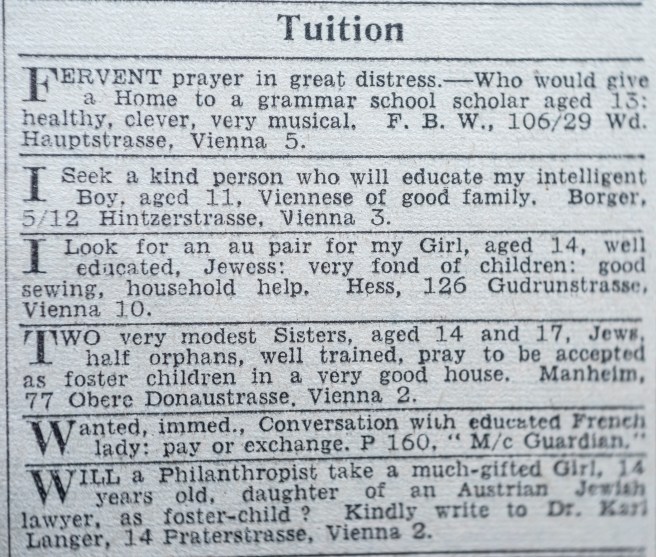

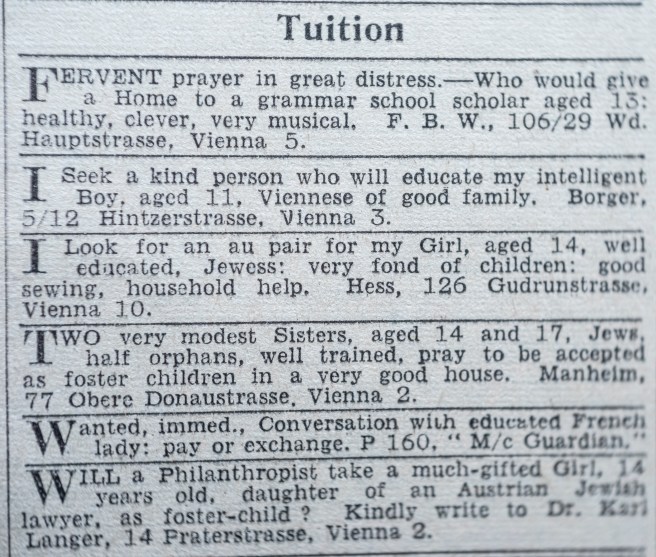

That’s as much of the story as Julian knew. No details. His father never talked about what happened. But not long ago, through an odd coincidence, Julian discovered that his grandparents had taken out a three-line ad in the Manchester Guardian—the previous name of the newspaper where he works—looking for a Brit who would take in his son. He started poking about and discovered that other Viennese Jewish families had done the same and that scores of Viennese children had found refuge from the Nazis because British citizens responded to these pleas. The result of his subsequent investigation is a wonderful book that is both a personal memoir of hidden history and a gripping account of the fates of these Jewish children, including his dad: I Seek a Kind Person: My Father, Seven Children, and the Adverts That Helped Them Escape the Holocaust. This is quite the moment to be writing about Nazi authoritarianism and the Holocaust. Julian was kind enough to talk with me about the book and what insights about today he’s gained from digging into the past.

How did you first uncover this unknown past about your father?

It was the archivist at the Guardian who found it. In late 2020, at the end of the first Trump term, I was talking to an American immigration lawyer. She was trying to stop the deportation of West Africans, in particular Cameroonians, to their home country, where, in the midst of civil war, they were likely to be killed or tortured. She made a remark about how we keep reliving the same traumas, generation on generation. And she mentioned how her dad had escaped from Vienna in the late 1930s, and she said it had something to do with the Manchester Guardian, the original name of the newspaper. It reminded me that in our family lore the Manchester Guardian had something to do with my dad coming out of Vienna.

This gave me the idea of asking our archivist. Because the Guardian was coming up to its 200th anniversary, I thought it might make for an interesting story. I mentioned to him there was something about my father. The next day, he wrote back and said, “Is this it?” Attached to the email was an advert I’d never seen before. I had thought that maybe there had been an article in the paper about Brits taking in Viennese children. I had no idea there had been an ad with such a personal plea.

The wording of it was straightforward but emotional: “I Seek a kind person who will educate my intelligent Boy, aged 11. Viennese of good family.”

When did it appear?

On August 3, 1938. This was five months after the Anschluss, and the lives of Jews in Vienna were becoming more precarious with every passing day. They had lost their jobs, their livelihoods. My father, like other Vienna Jews, was removed from his school and put into a separate Jewish school. I only learned much later some of the things that happened to my family in those months, because this was something we never talked about. This advert opened the door to the buried history of my family.

“Children could leave without having to pay the various exit taxes the Nazis demanded. Parents had to decide to send their children away, not knowing if they’d be able to join them.”

What happened with the advertisement your grandfather placed? Were there many responses?

My father was lucky that my grandfather did this early. These adverts began to appear late July 1938. A couple of Welsh school teachers in Caernarfon, Wales, who were looking for ways to help saw it. They could see what was happening in Central Europe. They wanted to make a difference and help in any way they could. They started corresponding with my grandparents. They even traveled down to the Home Office in London to make sure the paperwork was speeded up. At the time, you could get a child out of Austria if or she had a sponsor in a destination country willing to look after them and pay for their education. It was much harder for adults. So Jewish parents in Vienna had to make this decision. Do we all stay together, or do we at least try to save our children?

How long did the process take?

The advert was published in August, and in October, he was traveling to the UK. At this point, the Nazis were focused on getting Jews out. This was before the final solution. Children could leave without having to pay the various exit taxes the Nazis demanded. Parents had to decide to send their children away, not knowing if they’d be able to join them.

After you saw the ad, you realized there was an untold story here not just about your family. What did you do next?

After first experiencing the surprise of seeing my grandparents pleading for the life of my father, I realized he was not alone. In that block of adverts, there are five other kids. So I searched the archives and found 80 children advertised this way in the Manchester Guardian. It seemed obvious to me, as a journalist, that I had to find out what happened to all of them. That is the starting point of the book.

Of those 80, how many did you track down?

Mostly all of them. I was able to find out what happened to them. But when it came to locating those for whom there was someone who could talk about them, that was a smaller number. Within that group, there were seven who left very full accounts of what had happened to them, mostly in memoirs written for their families. There was one survivor of the children from these adverts still alive, in her 90s, and living in Connecticut. I came across her late in the project, after I had despaired of finding anyone still alive. I mainly talked to the children of these people. In each case, I would send them the advert. And in all but one case, they’d never seen or heard of the advertisement.

What happened to your father’s parents?

They both survived. His mother got out of Vienna with a visa for domestic work. There was a shortage of maids at that time in Britain. She was able to travel out of Vienna with my father. But her visa did not allow her to have a child with her in Britain. So she could not look after him or stay with him. Then, with the help of his foster parents, they were able at the last moment in 1939 to obtain a visa as an agricultural laborer for my grandfather. That part of the family all survived. Others did not.

But did they all unite at some point?

They never lived together again as a family. My father stayed with his foster parents in Wales until he went to university.

The book starts with a dark day in 1983 when you’re in your 20s, come home, and learn your father, a lecturer in psychology at Brunel University, has just committed suicide. Is there a connection between that and the story you’re telling in this book?

His foster mother definitely thought so. When my father took his life, it was my job to ring round people, and the person I left until last was his foster mother. Her immediate reaction was to say he was Hitler’s last victim: “They got to him in the end.” This came as a complete shock to me. It was something we just didn’t talk about. We didn’t talk about the past. In the note he left, he didn’t mention any of this. But she was quite adamant about it.

Much later, when I was researching this book, I realized why she seemed so certain. That’s because she was the last person he went to see before taking his own life. Tragically, she was away that weekend. He hung around the house for a little bit and then disappeared. When I called her, she knew that he’d come looking for her and that she’d been away. She felt he was trying to revisit that part of him, the boy who turned up as an 11-year-old refugee on her doorstep, and wanted to reconnect with that part of his life. At the time that didn’t mean much to me or our family because it was a piece of his life we didn’t talk about. It took on greater significance nearly 40 years later when I found the advert and began investigating my father’s early years.

“We could now remember people who had died under the Nazis who had been completely blotted out of our family history. We grew up thinking that as a family we survived scot-free. But it turned out there had been people who had perished in our family.”

The British are famous for being reserved when it comes to their emotional lives. Did you ever have any inkling of how your father’s experiences as a young boy—living in Nazified Austria and escaping—affected him?

There’s the British stiff upper lip. He definitely wanted to see himself as British. But I also found this attitude was widespread among these refugees. At least half of them did not mention the past and the adverts to their families until quite late in life, when they came under heavy pressure to talk about it. I also found this among the survivors from the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. The vast majority did not want to burden the next generation. It was a conscious decision: The trauma stops with me, and the next generation shouldn’t know. I believe that was his approach, and that was why he rebuffed any attempt to talk about his past. I once tried to do a school project on the Anschluss, thinking he’d help me. But he was very standoffish and did not want to get involved.

You’re best known as a foreign correspondent for the Guardian covering crises and foreign affairs around the globe. What was it like to write a memoir?

It goes against the grain in news-oriented journalism to write in the first-person singular. It was counterintuitive for me and felt self-indulgent. But the driving force behind writing the book was chronicling the extraordinary stories of these seven survivors. And the price for doing that was to tell this very painful story of our family that we had tried to block out. That ended up a blessing, because I found out a lot that had been hidden from our family that we could be proud of. We could now remember people who had died under the Nazis who had been completely blotted out of our family history. We grew up thinking that as a family we survived scot-free. But it turned out there had been people who had perished in our family. They just were not mentioned; their pictures were not on our walls. I’m grateful the book pushed me in a direction so that they now will be remembered. I went to visit their graves in Vienna—for those who had graves. On each it says, “unvergessen.” Unforgotten. That was a promise not kept. This book was a way of redeeming that promise.

You say some of these stories of these children are remarkable. Give me one.

Can I give you three? One is a guy called George Mandler, who lived very close to my dad in Vienna and was just a bit older. He came to Britain. But many Jewish refugees there in 1940 thought Britain was going to fall. Most of the kids in this book ended up getting on boats and going to the US. He did that and later signed up with the US Army and became one of the Ritchie Boys, an organization of refugees—many Jewish from Central Europe—who were trained to be intelligence officers and sent back to the front lines to interrogate German prisoners and conduct counterintelligence operations. (They were trained at Camp Ritchie in Maryland.) Mandler helped to chase the remnants of the SS through the forest of post-war Germany. He and two other Ritchie Boys came across an SS hideout in the middle of the woods in Germany and discovered a trove of Nazi cash. They decided to divide the loot among themselves as a kind of restitution and never told anyone else—until he wrote about it in a memoir for his family.

There was one girl who ended up in the Shanghai ghetto, a forgotten episode of the Holocaust. After Pearl Harbor, the Japanese took control of the international settlement in Shanghai and didn’t know what to do with the Jews. After Japan and Germany became allies, the SS showed up and advised the Japanese to put all the Jews on an ocean liner and torpedo it. That was too much for the Japanese, and, as kind of a compromise, they rounded up the Jews, placed them in a ghetto, and significantly worsened conditions. But the majority of these Jews survived. This woman, Gertrude Langer, in a long interview about Shanghai, gave a fantastic description of what that was like and also described pre-war Shanghai, a town essentially run by two Iraqi Jewish families and like a little Vienna. This was a whole episode of Jewish history I knew little about.

The third one is a boy named Fred Schwarz, who didn’t get as far as Britain. He got stuck in Netherlands, in a Nazi transit camp called Westerbork, and then was transferred to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. He and his brother survived all of it, and he described their harrowing experiences in intimate details in a book he published in Dutch called Trains on a Dead Track. It’s one of the most extraordinary accounts of survival I’ve ever read. It’s so intimately and precisely remembered, and he recounts these extraordinary scenes at the end of the war, when the camp inmates and their SS guards were both desperately trying to flee the Red Army and reach the American forces.

Working on this book, no doubt, caused you to think more about the Holocaust than we are generally accustomed to doing. But as a journalist, you’ve covered many horrors and genocidal actions. Did working on this book change how you see the Holocaust?

No matter how black or dark an idea we have of the Holocaust, it’s still impossibly tainted, because all our accounts of the Holocaust are from people who survived it. This book contains the tales of survivors, but I’m very aware these are the stories of a small minority who got away. The great unknown is all the stories of the people who did not survive. Maybe that is so overwhelming and too difficult for us to absorb. We learn our history of the Holocaust out of the mouths of people who survived.

The dead don’t speak.

Yes, the dead don’t speak.

There’s a tendency to make comparisons between what is happening now in the United States and what occurred in Germany and Austria in the 1930s. I believe we should learn from history but also be cautious in drawing parallels. After spending so much time researching what happened in Vienna, which was a liberal and cosmopolitan city where Jews had become well established in the highest reaches of society, do you see anything from that period relevant for Americans today?

Several things. One is that among these well-established Jewish families was a conviction that it couldn’t possibly happen here. The Nazis could come in, but it couldn’t last too long, because we are too civilized, and Vienna is too civilized. In that situation, it was the pessimists who survived and the optimists who were killed. Similarly, it was the wealthy Jews who were killed. They had more to lose by leaving, so they stayed.

“This is a reminder of how fragile are the things that we take for granted in terms of civilization and how quickly it can change—and how there are, without doubt, among us people who would enthusiastically take part in atrocities against their neighbors.”

The second thing I found notable was the overnight transformation of the Viennese people. The people who my family, my father, my grandparents saw as schoolmates, neighbors, and friends turned on them overnight when the Nazis arrived. When my grandfather was on his hands and knees with the other Jews being forced to clean the sidewalks, he was spat on and jeered by the people in his district. Many of them he knew. This is a reminder of how fragile are the things that we take for granted in terms of civilization and how quickly it can change—and how there are, without doubt, among us people who would enthusiastically take part in atrocities against their neighbors. There are potential psychopaths among us. What matters is how permissive the environment is. That’s a lesson we learned in Vienna, but also in Yugoslavia and in Rwanda—how fragile is this idea of civilized society.

One of the biggest surprises of the book for me was learning that my great aunt, who was a very diminutive and rather eccentric woman who dressed like it was still the 1930s and who was a terrible hypochondriac and neurotic—a figure of some derision within our family—was a hero of the French Resistance. She was a communist who went to Paris and then to the south of France and became part of a German-speaking network within the resistance that was used to infiltrate German camps, bases, and office. Her son, who was like a brother to my father, was sent to Austria to report on factories and if necessary, sabotage or foment unrest. But the Gestapo learned the identities of the members of his network and came for him. He ended up being taken back to Vienna and tortured to death by the Gestapo.

Our family didn’t know any of this history. My great aunt knew but she didn’t tell anyone. After the war, she went back to Vienna. Her husband and her son were dead, and she lived out the rest of her days a sad figure, existing rather than living. As incurious children, we would visit her and have no idea of her history and what she had been through. That’s a powerful lesson. You just don’t know about people.