In modern America, religious education is offered in private schools or in a homeschooling setting. Public education, by contrast, is secular, because the government is not in the business of sponsoring religious indoctrination. But in two cases the Supreme Court heard over roughly the last week, the justices appear ready to throw out public education as we know it and usher in a new era where tax dollars flow to religious schools and religion can dictate what is taught in public classrooms. When the decisions come down, public education may change forever.

“This is taxpayer-funded, state-sponsored religious indoctrination. You’ve just got to call it what it is.”

On Tuesday, the justices heard arguments in Oklahoma Statewide Charter School Board v. Drummond, a case over whether Oklahoma must fund a religious charter school that carries out religious instruction and hosts religious activities, including mass. Rather than consider this an affront to the separation of church and state, four Republican-appointed justices appeared outraged at the idea that a state would fund a charter school focused on language immersion or the arts but not one focused on religious instruction. Without ever acknowledging that the the First Amendment’s establishment clause (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion”) prohibits government-sponsored religion, several expressed palpable anger that allowing only secular charter schools was a form of anti-religious discrimination.

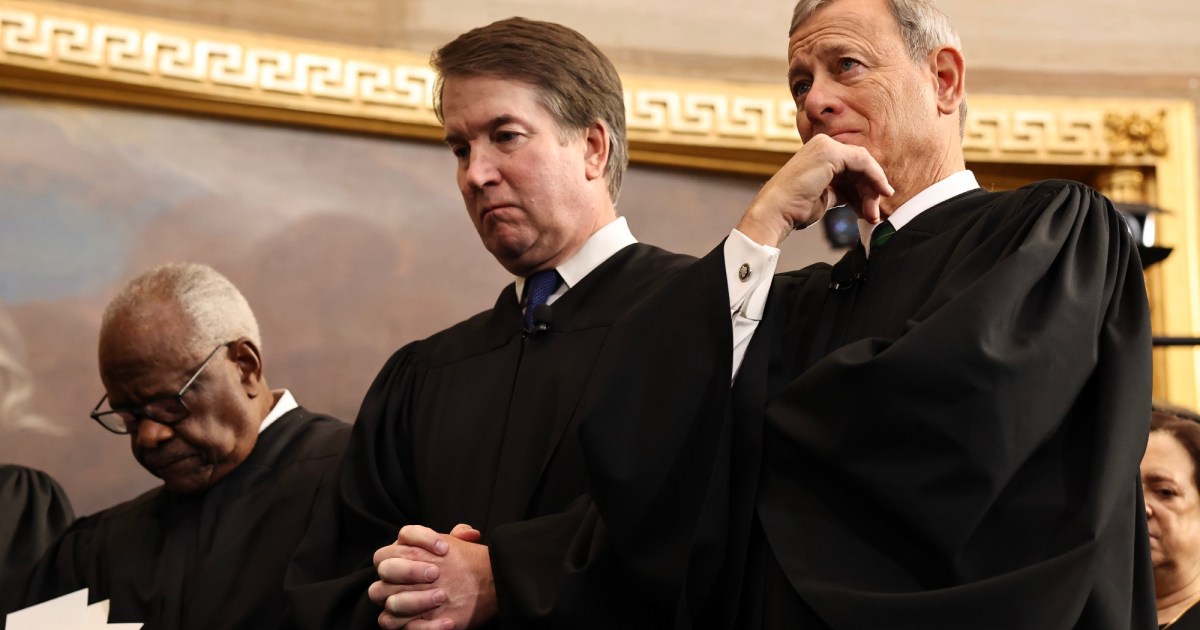

“All the religious school is saying is ‘Don’t exclude us on account of our religion,’” Justice Brett Kavanaugh said. “If you go and apply to be a charter school and you’re an environmental studies school, or you’re a science-based school, or you’re a Chinese immersion school, or you’re a English grammar-focused school, you can get in. And then you come in and you say, ‘Oh, we’re a religious school.’ It’s like, ‘Oh, no, can’t do that, that’s too much.’ That’s scary.” He continued: “You can’t treat religious people and religious institutions and religious speech as second-class in the United States… And when you have a program that’s open to all comers except religion… that seems like rank discrimination against religion.”

The case comes out of Oklahoma, where state law mandates public charter schools be secular. Nevertheless, the Catholic archdiocese of Oklahoma City and the diocese of Tulsa sought to create the country’s first religious charter school. Called St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, it would be an online school that would infuse Catholic teaching in its curriculum and require students to attend religious programming. The Oklahoma Statewide Virtual School Board granted the charter, but Oklahoma’s Republican attorney general, Gentner Drummond, asked the Oklahoma Supreme Court to order the board to reverse course. “This is not [about] free exercise of religion,” Drummond has said. “This is taxpayer-funded, state-sponsored religious indoctrination. That’s what this is. You’ve just got to call it what it is.”

The Oklahoma Supreme Court agreed that the charter was illegal because Oklahoma law requires public charter schools be secular. So the board and St. Isidore appealed to the US Supreme Court. Justice Amy Coney Barrett recused herself because she is friends with a law professor who advised the school. The result at Wednesday’s oral argument was four GOP-appointees who appeared ready to usher in a new era of religious public schools, and three Democratic-appointees who opposed such a move. Chief Justice John Roberts was the only Republican appointee who did not tip his hand, though his questions showed he was skeptical of the argument against religious charter schools.

The arguments technically centered on whether public charter schools are indeed public schools or private entities. If they are public, as Oklahoma law defines them, then the guarantee against the establishment of religion is a stronger argument. But if the schools are actually private, as St. Isidore’s insists—along with the charter board and the Trump administration—then it is harder to argue that private religious entities should not be entitled to the same charter contracts as any other organization. Whether they are public or private, however, the bottom line is that charter schools are taxpayer funded, which means the argument is more broadly over public funding of religious education and whether to integrate religious instruction into state education offerings.

“Once you… approve one religion, not another religion, or this religion, there’s going to be strife.”

Justices Kavanaugh and Samuel Alito were the most vociferous defenders of the Catholic charter school, repeatedly suggesting that the only reason one might deny a religious institution tax funding to run a school is anti-religious bigotry. Alito went so far as to suggest that the Oklahoma constitution’s requirement to provide a secular public education was based on anti-Catholic animus. “This whole position that you’re defending seems to be motivated by hostility toward particular religions,” Alito said to Gregory Garre, a former US solicitor general representing Drummond.

Garre pushed back. “I don’t think that the court could treat any prohibition on funding that’s similar as simply motivated by bigotry,” Garre said. “If you did, then I think, frankly, the establishment clause jurisprudence with respect to public schools would come tumbling down.”

Listening to arguments, it seems possible that’s what Alito and some of his colleagues want. In recent years, the court’s GOP majority has increasingly removed the bricks separating church and state, including in the realm of schools. While the Constitution’s establishment clause used to protect separation, conservative justices seem to have decided that the free exercise clause mandates the state can do nothing to maintain it—freedom of religion is increasingly the freedom to bring religion into every corner of American life, including public education.

Alito also suggested that Drummond was motivated by bias against non-Christian religions because of comments in which he suggested Oklahomans might approve of Christian charters, but not charters by religions that the majority views with suspicion. Garre defended his client as simply stating the political reality of state-sponsored religious instruction: “Once you open up government programs and bring people in to becoming part of the government, and approve one religion, not another religion, or this religion, there’s going to be strife that comes from that,” he said. “It’s, frankly, one of the reasons why we have a religion clause in the Constitution to begin with.”

Kavanuagh pounced on Garre’s suggestion that the government picking and choosing which religions got public charter schools could create “strife.”

“It seems like strife could also come when people who are religious feel like they’re being excluded because they’re religious,” he told Garre. “I think you’re missing a portion of the country when you say strife would not result from that kind of outcome.”

As Kavanuagh’s comment demonstrated, the Republican-appointed justices seemed to feel that in America today, it is religious people who are the victims of discrimination and whose needs are ignored.

The Democratic appointees approached the case very differently. They seemed to squarely see public charter schools as public schools and that Oklahoma had the right to decide that its public schools should be nonreligious. Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson analogized the situation to a local government that solicits contracts to paint landscape murals on public buildings. If a religious painter proposed a mural full of religious symbols, Jackson queried, would it be a violation of his religious rights for the government to deny him a contract? “Would that person say ‘You are rejecting me as a painter because of my religion’… when, really, what the state is doing is saying ‘We are offering a particular public benefit and the particular benefit is a nonsectarian mural, a secular mural, and to the extent that you’re not wanting that, we’re rejecting your proposal?’”

The court is poised to deliver a one-two punch that profoundly changes public education.

Justice Elena Kagan stressed that in keeping with their faith, religious charter schools might not just teach religious beliefs as fact but also seek to upend state-mandated curriculums and nondiscrimination requirements. Today, St. Isidore’s might promise to teach the content required by Oklahoma law. But why couldn’t a Hasidic community in New York get the state to pay for a yeshiva that teaches only religious texts in Yiddish, Hebrew, and Aramaic? The attorney for St. Isidore’s couldn’t deny the possibility.

Kagan later asked Garre to share what he predicts would happen if the Supreme Court found that states must allow religious charter schools—essentially ushering in an era of public religious schools.

“First, every charter school law and the federal charter school program is unconstitutional, because they all require that charter schools be public schools and that they be nonsectarian. So we’re dealing with the confusion and uncertainty that’s created by that to begin with.” From there, Garre predicted some states might end charter programs altogether, disrupting education, while others would push forward and accommodate religious charters. He foresaw fights over whether federal law mandating education for disabled kids would apply to charters deemed to be private. Every aspect of this new education regime would go through the Supreme Court. He predicted litigation over which students can attend, who can teach (“can you have a gay teacher?”), and finally, over the curriculum itself. Questions over what can be taught will be mediated not through the local democratic process but through nine Supreme Court justices.

This case alone will be a bombshell if the court mandates that states begin funding religious schools through their charter school programs. But this term, the Supreme Court is poised to deliver a one-two punch. Last week, the court heard arguments in Mahmoud v. Taylor, in which it considered whether religious parents could opt their kids out of lessons that did not conform with their beliefs. Again, the GOP-appointed majority appeared ready to side with the plaintiffs and allow religious parents to pull kids from the classroom when material they object to is taught—a policy that threatens to create a backdoor through which religious parents have veto power over elements of the curriculum and classroom discussion.

In any school that cannot accommodate children leaving the classroom and being provided alternate materials, the religious preferences of a minority seem destined to dictate the curriculum for all. The likely result is the wide elimination of LGBTQ content. Teachers may fear answering a question about a gay politician, for example, or even displaying a picture of their same-sex partner on their desk.

If the justices decide in the next few months to allow religious opt-outs in public schools and the creation of religious charter schools, it’s hard to see how public education will not change profoundly. In many districts, together the decisions would likely mean the only publicly-funded school options would be either explicitly religious or circumscribed by the religious preferences of certain parents.

President Donald Trump, whose administration has argued for the religious interests in both cases, has ordered the shuttering of the Department of Education and threatened to withhold funding to schools that engage in diversity, equity, and inclusion programming. But the president’s ability to direct public school curriculums is limited, because public education is primarily controlled at the state and local level.

The Supreme Court, on the other hand, can dramatically reshape public education, reaching across geographic boundaries to make decisions for individual districts and schools. When it comes to the religious right’s agenda of returning religion to public classrooms, it’s not the administration that is to be feared the most, but the Supreme Court.